Tree planting in Yorkshire, © National Trust Images

As the climate changes, one of the challenges for those involved in land management is how to engineer the natural environment to make it more resilient to drier summers, wetter winters and an increasing number of storms.

In West Yorkshire, the National Trust and Yorkshire Water have – with the help of government agencies and NGOs – embarked on a plan to restore woodlands, install natural flood management and boost biodiversity across 5,500ha.

Over the next three years, the Landscapes for Water partnership hopes to plant an estimated 200,000 trees, comprising a mixture of broadleaf native species, including oak, rowan, birch and hawthorn.

As well as providing habitat for wildlife, storing carbon and preventing peat erosion, these trees will reduce the likelihood of downstream flooding. They will form part of the White Rose Forest, the community forest for North and West Yorkshire, and have been funded by the Trees for Climate grant programme, part of the government's Nature for Climate Fund.

The Landscapes for Water project will also install 3,500 leaky dams, funded by the West Yorkshire Combined Authority. Leaky dams are a deliberate strategy to help reduce the risk of flooding by slowing water down: these will comprise a mixture of stone, willow and turf dams, which will slow the flow of water through the River Colne and Calder catchments and naturally manage downstream flooding.

Flood management scheme evolves through collaboration

The project is an offshoot of National Trust and Yorkshire Water's Common Cause partnership, set up in 2018 to increase climate change resilience across both landholdings. The first project under the Common Cause banner, Growing Resilience, installed 435 leaky dams to slow down water and reduce flooding, and planted 120,000 trees across 184ha at Gorpley reservoir in 2019 and 2020.

White Rose Forest, which is under Kirklees Council's jurisdiction, approached utility company Yorkshire Water in 2015 to discuss two separate areas of tree planting at Gorpley in Calderdale and Butterly in Kirklees. This evolved into a project with other partners including the Woodland Trust and National Trust, which had contiguous holdings next to Wessenden and land close to Gorpley.

External consultants carried out bird surveys and there were many discussions between other stakeholders such as Calderdale Council, RSPB – due to the presence of Linaria flavirostris or twite, which is on the Red List in the UK – and the Environment Agency.

The National Trust was granted a short-term licence to occupy the land to install natural flood management measures, for which it had secured investment from the local growth fund. The Woodland Trust was granted a 25-year lease over the area for planting and management of trees.

Before the first of these were planted in 2017, the land at Gorpley had become vacant and so was not subject to any tenancy or third-party rights, neither was it in a site of special scientific interest or a special protection area. This meant there were fewer hoops to jump through to start planting. Relevant permissions were obtained by the Woodland Trust and the work funded by the White Rose Forest.

Partnership formed to expand on initial success

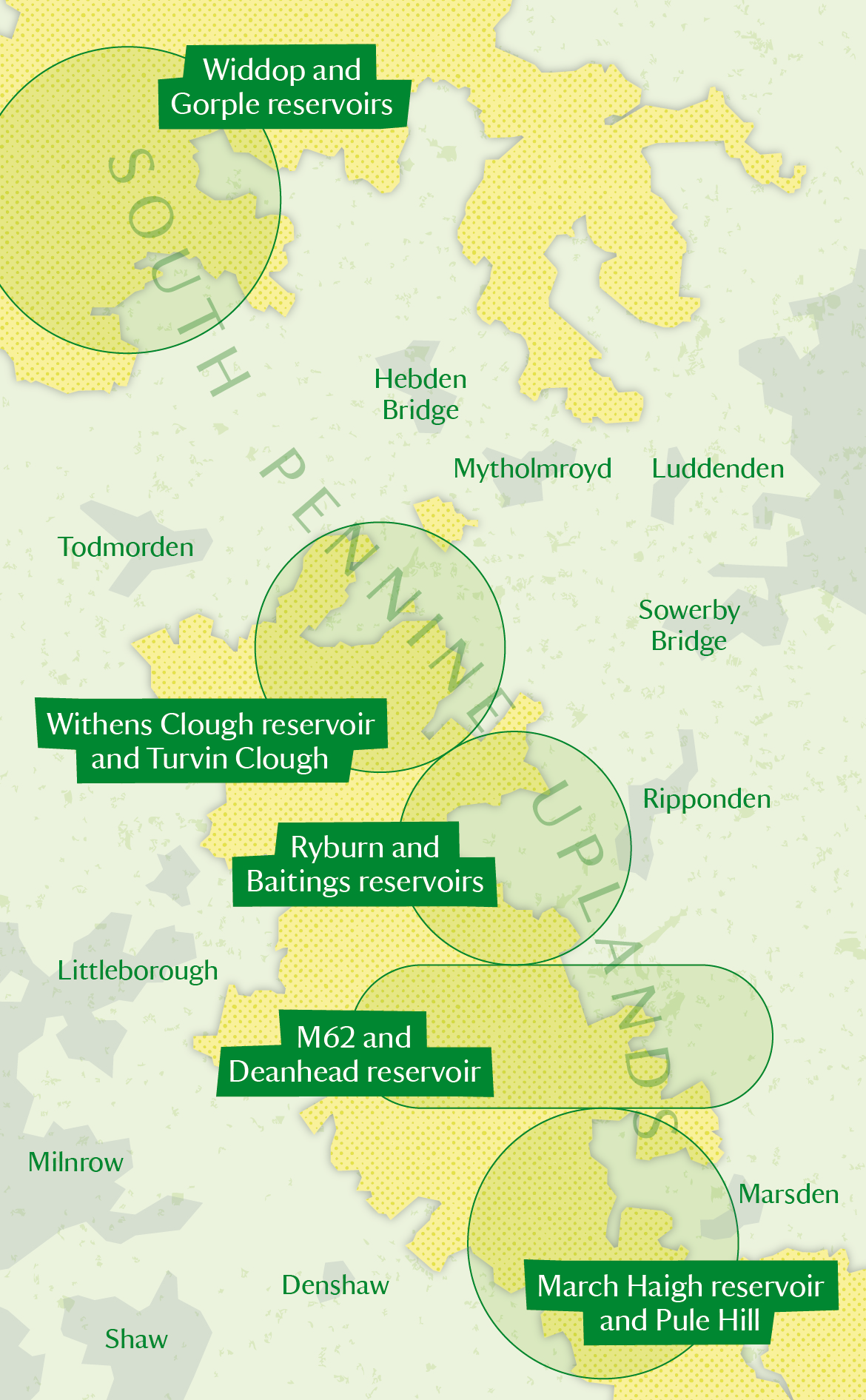

Aiming to build on the success of this joint project, Yorkshire Water and the National Trust committed to a formal partnership and drew up a draft agreement for the Landscapes for Water proposal the following year. The initial plan was to install 7,000 leaky dams and plant 950ha of trees from Heptonstall Moor in the north down to Marsden Moor in the south.

Yorkshire Water had already been in touch with some of its tenants in these areas to discuss possible tree planting, and consulted them again about this specific programme of work and the area that had been tentatively mapped for woodland.

Due to the size of the area, the project was broken into five phases to make it easier to consult the tenants or stakeholders in turn. Surveys for peat, vegetation and birds were carried out by different external consultants at each site, and survey data was considered for fish and other wildlife, which again helped to inform mapping.

Land that had been classed as containing deep peat, sensitive vegetation – namely grassland fungi – or rare bird habitat had to be discounted. The woodland design was thus informed by surveys of each of these, as well as by the initial assessment of impact report and landscape character assessment.

The first two areas of focus were Baitings – the land around Ryburn and Baitings reservoirs – owned by Yorkshire Water, and March Haigh and Pule Hill, owned by the National Trust. The project was scheduled to start in 2021/22, but first there were a number of challenges to overcome.

Figure 1: Moorland restoration as part of Landscapes for water project covers 5,500ha shown by the shading. © National Trust Images

Works proposed at Baitings

- 7ha of trees planted and 39 dams installed at time of writing at Ryburn and Baitings reservoirs, extending existing woodland edges around these and new habitats on the moorland edge

- 250 leaky dams for natural flood management in a variety of constructions, including turf or peat, willow and stone planned by end of this year

- Additional 4.5ha of woodland planting on tenanted land under an HLS agreement is on hold due to uncertainties around RPA clawback

Works proposed at March Haigh and Pule Hill

- 63ha of trees planted in cloughs around moorland edge and western flank of Pule Hill

- 1,200 leaky dams planned by the end of this year for natural flood management, using turf or peat, willow and stone among other material; 328 dams installed at the time of writing

- Bracken growth monitored in first year to target treatment of problem areas the next, reducing chemical use as much as possible; contractors and volunteers to carry out further cutting and bashing of bracken to deplete the rhizome store until trees are established

How to use feedback from land users to inform proposals

The Landscapes for Water project area includes land either under farming tenancies or grazing commoners. Consultation with tenants and commoners has been key throughout the design and development process, and significantly shaped the overall plans.

As well as permission for tree planting, the need for fencing also had to be negotiated and agreed with tenants, along with any gates or stiles needed. Where fencing was necessary on the common, consent was required from the secretary of state for the environment, food and rural affairs before carrying out the work.

While we found that most tenants and commoners were happy to consider tree planting in some form, their feedback was essential when it came to designing a scheme that worked for everyone and allowed them to continue sustainable farming. In some cases, this involved removing land parcels from the scheme, creating gaps at key access points, or changing the shape of parcels to help stock gathering.

After the surveys were carried out, we consulted again with tenants and commoners, and remapped land parcels on the Rural Land Register because fencing had been erected and land use was changing.

To avoid double funding, land subject to tree planting had to be removed from existing or new agri-environment schemes. Support for these pockets of land had to be guaranteed through the Trees for Climate funding so that the tenants were sure that they wouldn't be financially disadvantaged by switching to planting.

Tenants have been wary of removing land from existing schemes as it isn't certain whether the Rural Payments Agency (RPA) will try to claw back previous payments given that Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) obligations, from which such land currently gains funding, would no longer be met.

How we worked with tenants

At Baitings, negotiations were led by a chartered surveyor for Yorkshire Water who contacted every tenant farmer in the first instance. All proposed land was tenanted, but there were no sporting tenancies or third-party shooting rights, and no commons in the first phase.

The area included four tenants. Some have more than one tenancy in the area and one was not keen on tree planting initially, but gradually became more interested. However, when the final mapping was presented, the proposed planting areas could not be agreed and therefore this area was removed from the scheme.

A second tenant has been willing from the outset and readily agreed to all the mapping changes. Unfortunately, due to the uncertainty that would result from removing the parcels from the HLS, the planting in this area is on hold at the time of writing but will continue when we are clear that the stewardship funding will not be jeopardised.

A third tenant had also extended the period of their HLS scheme but was confident that removing these parcels from stewardship would not have a detrimental effect on this.

The fourth tenant in this area had decided not to extend their HLS and started looking into Countryside Stewardship (CS) options instead. This meant that splitting the land parcels was relatively straightforward.

An understanding agent acted on behalf of the last two tenants, who liaised closely between the agent and the RPA, while our project landscape architect sorted out the mapping.

The tenant agent managed to split all the proposed tree planting parcels, including all the new fencing, with the RPA. These areas were remapped so that some of the original parcels stayed as they were and the rest were put into the planting scheme. This enabled the woodland application for this area of 21ha and 31,000 trees to progress. Planting has been carried out in two phases: the first was in spring last year while the second will be planted this spring.

The tenant agent managed to split all the proposed tree planting parcels, including all the new fencing, with the RPA. These areas were remapped so that some of the original parcels stayed as they were and the rest were put into the planting scheme. This enabled the woodland application for this area of 21ha and 31,000 trees to progress. Planting has been carried out in two phases: the first was in spring last year while the second will be planted this spring.

The tree-funding schemes have a built-in element of natural capital contributions that have been used as part of the forgone income. However, these initial two areas would not have been satisfactorily compensated, so Yorkshire Water made up the shortfall.

In all, the process of getting tenants' agreement just for this one area has taken five years. Most of them have chosen to have the planting area as part of their tenancy, meaning that this and all future responsibilities for it will revert to them at the end of the 15-year maintenance period.

'In all, the process of getting tenant agreement just for this one area has taken five years'

Turf dams slow water down helping to mitigate flooding. © National Trust Images

Stone dams with a gap in the middle slow water helping to mitigate flooding. © National Trust Images

Where surveyors and farm advisers used their expertise

The Marsden Moor Estate, which is owned by National Trust but is also common land, is a 2,300ha site of special scientific interest, a special protection area and a special area of conservation due to the ground-nesting bird population and blanket bog habitat.

The active commoners' association comprises around 15 members, six of whom currently exercise their grazing rights. March Haigh and Pule Hill fall into the same common, CL39, with different commons graziers involved in each, and the Landscape for Water partnership has planted 63ha of trees there. All graziers were consulted as the plans were developed, and their feedback on the woodland design was taken into consideration.

The land was under two HLS agreements that came to an end in 2023. The RPA offered the option to extend the agreement for a further five years to the Marsden Moor Commoners' Association. However, the inability to remove areas from the scheme at the point of extension would have meant that the tree planting could not go ahead.

The National Trust's rural surveyor and farm adviser were key to dealing with this challenge, and helped to identify a way forward. Working with Natural England, they realised that a new CS scheme would be more lucrative for the commoners' association, and this would allow the remapping of parcels and the removal of tree-planting areas from the stewardship scheme so the woodland creation could proceed.

The White Rose Forest provided an element of income-forgone funding through the planting scheme, to ensure that the association didn’t lose out because the planted areas would not be part of the CS scheme.

The project wanted to avoid fencing as much as possible, but a small amount was required to prevent sheep entering the planted parcel on Pule Hill. This required a further consultation process and application to the secretary of state for the environment, food and rural affairs for consent to fence on the common.

For the main area of planting, the decision was made to work with the cattle grazier to use NoFence collars to keep them out of planting areas, rather than use fencing. This is expected to benefit both the land, by directing cattle to graze target areas, and the grazier, as the NoFence system can be used to monitor livestock more closely.

Project offers lessons in pragmatism and engagement

There have been many elements of the project to align before work could begin, and the scope has been daunting at times, but it is heartening to see how far we have come. Working together can take special efforts, overcoming differences of culture and managing joint resources; but over the past four years we have learned to play to our strengths.

We now know that it's important to aim high in terms of scope, as land parcels are apt to be curtailed over time as survey results identify areas in need of protection, or plans change to accommodate the needs of farmers and graziers. For instance, while the first Landscapes for Water proposal covered 7,000 leaky dams and 950ha of tree planting, the final proposition has been scaled down to provide 3,500 leaky dams and 350ha of trees.

Early communication with tenants has been vital, as they can have many and complex reasons for wanting to steer planners towards certain land parcels for tree planting. There are often also complicated calculations to be done before they can approve the work in principle.

Tenants are paid directly by the RPA, which will only deal with them as they are the agreement holders. This means that if a tenant needs to amend land parcels they need to pay a rural surveyor to do so, but then there may be an agreement for the costs to be covered from the project.

If you are considering a similar programme of works where there are many tenancies, remember that payment schemes are a big part of the tenant agreement process, so make sure you consider whether the proposed work will affect their current schemes. If so, can they transfer to another? If the income forfeited is higher than the payment scheme offers – or there is a gap between schemes – who will make up the shortfall?

Make sure you engage key statutory bodies early, too, as their support is vital in getting a project through the paperwork and permissions stage. Not all individuals interpret the legislation in the same way, and building relationships is important so applications don't get held up or denied.

The Landscapes for Water programme is ambitious, but we believe large-scale work such as this is vital to protect the unique habitats, wildlife and communities of the South Pennines. Together, Yorkshire Water and National Trust are among the largest landowners in Yorkshire, and we have a responsibility to restore our uplands while making sure tenants can continue to use the land sustainably.

Carol Prenton MRICS is lead SSSI and portfolio surveyor at Yorkshire Water

Contact Carol: Email

Catriona Cormack is Landscapes for Water project support coordinator

Contact Catriona: Email

Jess Yorke is land, outdoors and nature project manager

Contact Jess: Email

Kate Divey-Matthews is land, outdoors and nature project manager at National Trust

Contact Kate: Email

Maddi Naish MRICS is estate manager in Lancashire and West Yorkshire

Contact Maddi: Email

Sarah Warwick is senior communications and marketing office at the National Trust

Contact Sarah: Email

Related competencies include: Land use and diversification, Management of the natural environment and landscape, Sustainability