© Marshalls

Visual impairments can make navigating uneven or changing terrains challenging. Travelling short distances can become impossible, and the risk of trips, falls and serious injuries increases.

Yet as we age the reactivity and sensitivity of our eyes decrease, meaning we're less able to notice differences in colour, depth and distance. All of this contributes to gradual declines in our vision.

Sight loss more frequent as population ages

As the size and average age of the UK population continue to increase, the prevalence of partial and total sight loss due to age-related macular degeneration, glaucoma, cataracts and diabetic retinopathy will increase substantially.

In fact, research suggests that by 2050, the number of people with partial sight loss in the UK will double from present figures to more than 2.7m, and the number of people living with total blindness is expected to rise to nearly 400,000.

There are several reasons that the number of people living with these conditions is increasing.

On one hand, we have a rise in lifestyle-related illnesses such as diabetes, which can be caused by unhealthy diets, obesity and high blood pressure; and, if left untreated, diabetic retinopathy can lead to permanent retina damage and sight loss.

On the other hand, many of the conditions associated with blindness are a natural consequence of the ageing process. So, as advances in medical care mean people are living longer, the growing prevalence of visual impairments is only to be expected.

This demographic shift means the built environment has been forced to adapt to better accommodate users with visual impairments and other disabilities associated with ageing.

Under Approved Documents K and M, new works are already held to such standards, but building owners have further responsibilities under the Equality Act 2010, related to making reasonable adjustments to ensure spaces are accessible and giving due regard to the likely needs of building users.

Nosing helps highlight step edges

Stairs present a particular hazard to the visually impaired, given the risk of tripping or falling. Among the adaptations to make these more visible and negotiable is stair nosing. Sometimes known as external step nosing, this is the strip of material added to the leading edge of a stair or step, as shown in the image below.

Stair nosing on external concrete stairs with adequate colour contrast. © Marshalls

Well-executed stair nosing helps prevent falls by clearly delineating where one step ends and the next begins. Designers responsible for external stairs and stair sets – that is, stairs in series – can follow best practices by incorporating:

- colour contrast from the rest of the step

- textured or ridged surfaces for enhanced traction

- rounded edges to prevent people catching their feet

- durable, slip-resistant materials

- tactile paving at the top and bottom to alert individuals with impaired vision that they are approaching a change in terrain.

Approved documents support safety and access

The best practice identified above forms part of several pieces of guidance covering stair nosing in the UK, including two approved documents and two BSI codes of practice.

Protection from falling, collision and impact: Approved Document K provides guidance on how to comply with requirements for stair safety inside buildings and other internal environments, including specifications for stair nosing dimensions, profiles and materials.

Section 1.7 of the document applies to buildings other than dwellings – namely anything that is not a self-contained unit designed to accommodate a single household – and sets the following requirements.

- Make step nosings apparent: use a material that will contrast visually, a minimum of 55mm wide, on both the tread and the riser.

- Avoid, if possible, step nosings that protrude over the tread below. If the nosing does protrude, ensure that it is by no more than 25mm.

Appendix A defines visual contrast as '[t]he perception of a visual difference between two elements of the building, or fittings within the building, so that the difference in the light reflectance value is of sufficient points to distinguish between the two elements'.

In turn, the light reflectance value (LRV) is defined as: '[t]he total quantity of visible light reflected by a surface at all wavelengths and directions when illuminated by a light source'.

Access to and use of buildings: Approved Document M meanwhile includes specifications for nosings, focusing on helping people with visual impairments and mobility issues.

The guidance for stepped access to buildings other than dwellings detailed in section 1 of volume 2 is as follows.

- Nosings should be highlighted, and open rises avoided so people can appreciate easily where to place their feet.

- A so-called corduroy hazard warning surface is provided at the top and bottom landings of a series of flights to signal a change of level. In this context, such a surface will be a tactile hard landscaping material noticeably different to the adjacent ground surface.

- All nosings are made apparent by means of a permanently contrasting material 55mm wide on both the tread and the riser.

- The projection of a step nosing over the tread below should be avoided but, if necessary, must not protrude by more than 25mm.

British Standards advise on external stairs

BS 8300 parts 1 and 2 offer advice on designing an accessible and inclusive built environment, part of which includes the provision of further detailed recommendations for stair nosing.

- Nosing edges should be rounded or chamfered to minimise trip hazards.

- Nosings should extend the full width of stairs so they can be detected by cane users.

- Contrasting nosings should be provided on step risers and treads alike.

Although these requirements are not a formal part of the Building Regulations and do not directly relate to the Equality Act, professionals specialising in the provision of hard landscaping materials for commercial buildings generally agree that complying with them means you fulfil the act's requirements as well.

Light reflectance critical to distinguishing surfaces

One aspect of the regulations that surveyors often find daunting is specifying the correct contrast level for stair nosing, particularly as LRV requirements are not common considerations in many projects.

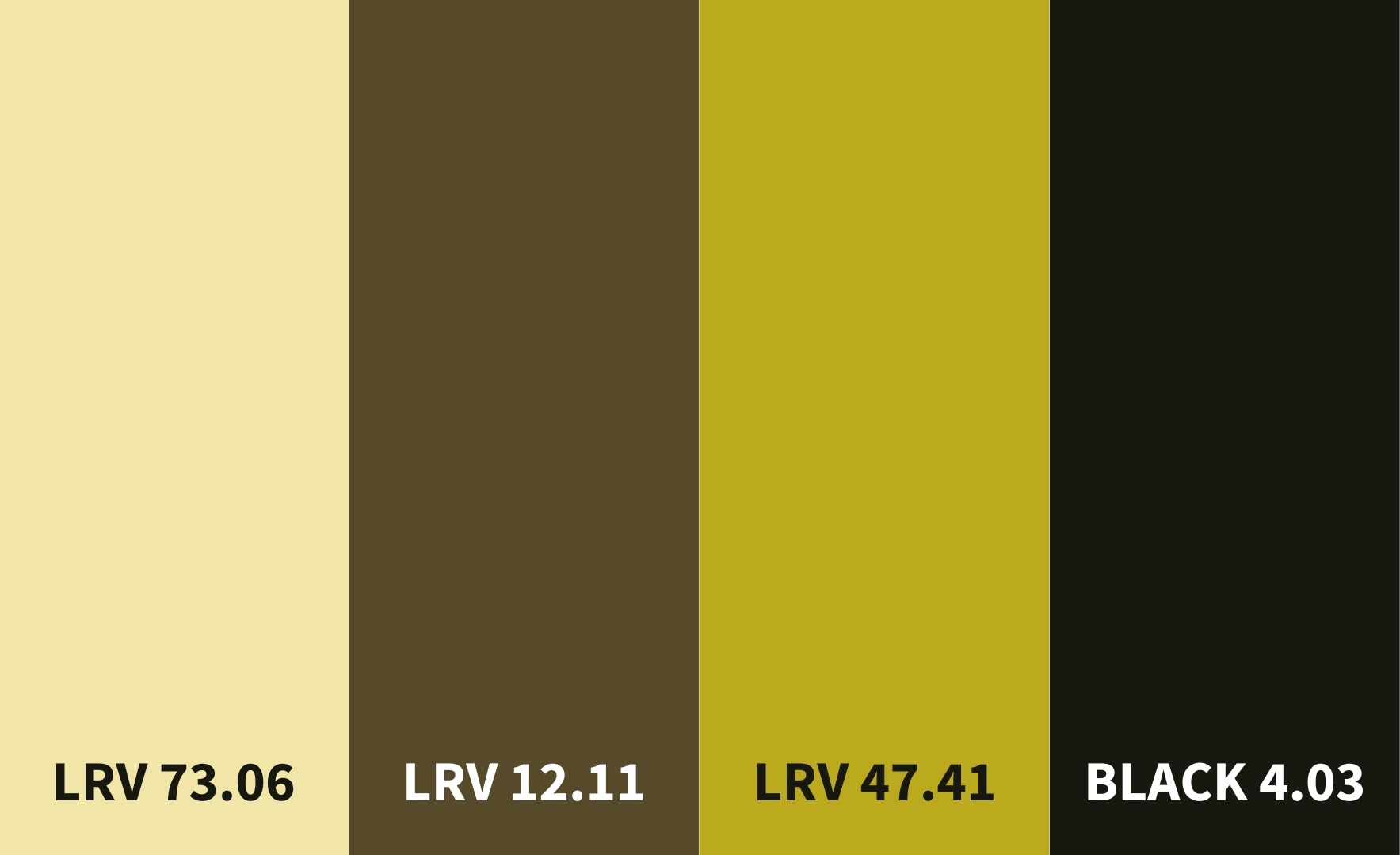

LRV measures how much light a surface reflects – black has an LRV of 0 since it reflects none, while white has an LRV of 100 since it reflects all light. The greater the difference in their LRVs, the easier it is to distinguish two surfaces. In Figure 1, for example, the colours are arranged such that each column contrasts sufficiently with the adjacent ones.

'One aspect of the regulations that surveyors often find daunting is specifying the correct contrast level for stair nosing'

Figure 1: Different colour contrast levels with LRVs. Source: Marshalls

Approved Documents K and M and British Standards all emphasise the importance of colour contrasting for stair nosings to support visibility, especially for those with visual impairments.

The specific requirements include incorporating a permanent contrasting colour on both the tread and riser of the nosing to clearly identify the start and finish of each step. The nosing and the rest of the step surface must have a minimum 30-point difference in LRV.

Practical conditions affect colour contrast

When assessing the colour contrast of nosings, surveyors should keep the following in mind.

- Nosings should be made of permanent, durable materials that will not fade, wear or peel with use and cleaning.

- Ambient lighting conditions can affect the perceived contrast levels, and colours that contrast well in bright light may be less distinct under artificial lighting or shade.

- The colours present in the surrounding environment, such as walls and floors, can also affect the contrast.

- Glossy surfaces can produce glare, reducing the effective contrast, so matt, satin or textured finishes are preferable.

To support the provision of adequate, lasting colour contrast, building control surveyors can recommend that designers and architects do the following.

- Consult material specialists and LRV charts to select nosing and step colours that achieve at least a 30-point difference in value.

- Request physical samples or mock-ups and evaluate them in the actual lighting conditions at the installation site.

- Avoid using the same material or colour for the nosing and step to prevent poor differentiation as it wears.

- Instruct contractors on the colour contrast requirements and periodically inspect during installation.

- Specify cleaning procedures that won't degrade or remove the contrasting nosing colour over time.

Design must be inclusive from the outset

Building control teams should ensure designers incorporate appropriate stair nosing in all public space developments from the outset to keep up with changing inclusivity requirements.

This represents a low-cost way of mitigating risks and reducing the potential for liabilities from accidents due to poor accessibility – and, more importantly, upholding our obligation to design environments that enable users of all ages and abilities to navigate safely and maintain their independence for as long as possible.

RICS Global Building Conservation Conference

25 September | 08:00 – 17:30 BST | Online

This year the conference showcases the very best of efforts to preserve and enhance heritage sites around the world, safeguarding their integrity and utility for future generations.

The event will address some of the ways in which both man-made and natural disasters are impacting the legacy of these heritage sites, examining the innovative techniques that conservationists use to respond to their region-specific challenges.

These insights will be delivered through sessions that include an examination of climate change and climate protection, post-conflict building restoration, and the opportunities and challenges created by repurposing buildings after a period of disuse.