On site © Antonio Cabello

I have always been passionate about historic buildings and conservation. Having qualified as a technical architect in 2003, I spent a few years practising in Spain before moving to the UK in 2011 in search of new professional challenges.

I initially planned to stay in the UK for just six months. But shortly after arriving I had the privilege of joining the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) and, encouraged by this experience, my six-month plan became an exciting career path that has lasted ten years – and shows no signs of stopping.

NTS played a crucial role in grounding and shaping my professional career in conservation – it gave me the opportunity to reinvent myself as a building surveyor and become chartered in 2014. This period was key for my professional development as I gained invaluable knowledge, experience and inspiration from being taught by some of the best conservation professionals in Scotland.

Coming round to accreditation

It was also during this period that I first heard about the RICS Building Conservation Accreditation. I was working towards RICS membership and, at that time, thought the accreditation was far from obtainable without extensive knowledge and experience.

In 2016, I accepted a role at consultancy GLM. Here, I faced conservation challenges without the safety net I had become accustomed to at NTS, where I had been surrounded by conservation-accredited professionals. Nevertheless, at GLM I started leading projects related to historic buildings on my own.

This allowed me to consolidate my knowledge and expertise, strengthen my skill set and gain a wealth of experience dealing with historic buildings. After a few years of continuous professional development, I realised that conservation accreditation was the natural next stage.

After some false starts with the process, it was not until the first UK lockdown in 2020 that I committed to becoming accredited, because I then had plenty of time. At that stage, I felt I had enough relevant projects from which to choose case studies.

Once I decided to apply, there were about three months until the deadline for submitting. I used that time to prepare my case studies and reinforce some of my theoretical knowledge by reading conservation-related books and other material.

Selecting projects to write up as case studies

I initially thought that a strong portfolio should contain case studies about high-value, complex conservation projects involving castles, palaces or mansions. So I felt concerned because I had not worked on many projects of this kind. However, after speaking to one of my professional mentors – who was RICS conservation-accredited himself, I realised that any historic building work can form the basis for a good case study.

I had to describe the process I followed when facing a conservation challenge and how we acted. We also had to detail the principles on which our decisions were based, and why specific actions rather than others were chosen.

Key points included the reasoning we applied in each case, the decision-making process, which considerations were prioritised, and how we gained understanding and assessed significance, while demonstrating the required skills for relevant competencies.

Having shortlisted a few projects, I then decided which were the most suitable to be used as case studies. My portfolio included a variety, among which were:

-

the repair of an old customs house and its conversion into holiday accommodation

-

the restoration and repair of a Victorian glasshouse

-

the restoration and repair of a 16th-century mill weir.

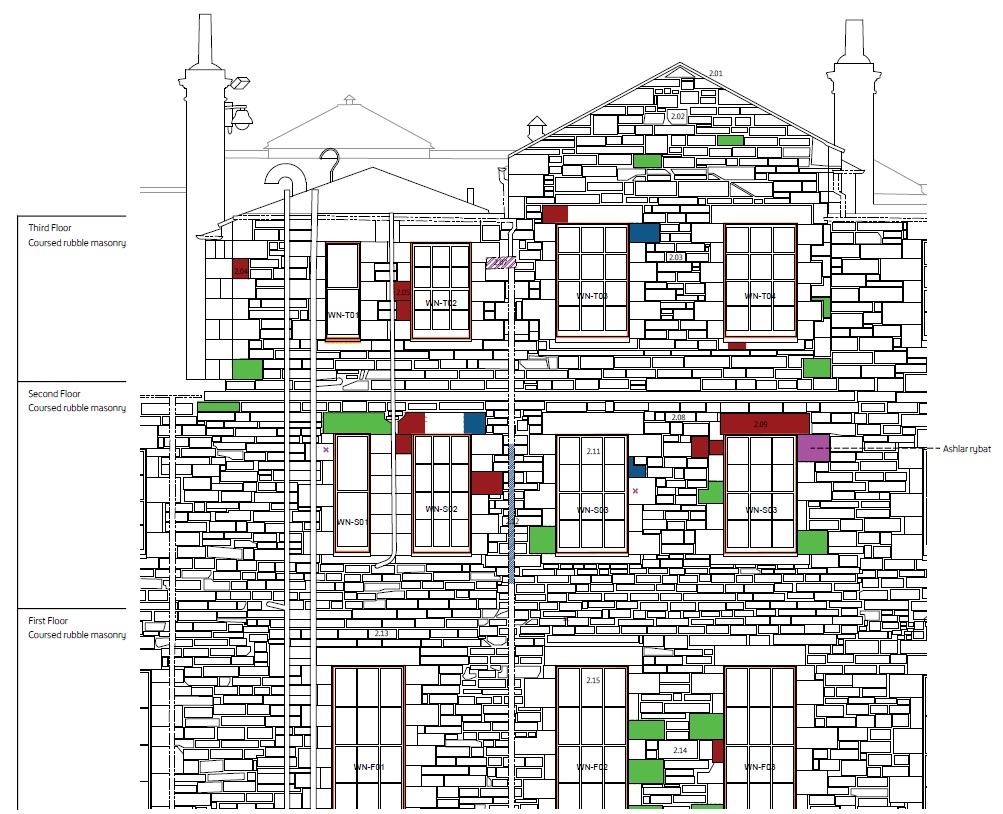

I also included two case studies on a Georgian country house with later Victorian and Edwardian additions. One study concerned external fabric repairs, which involved extensive repairs to the roof and stonework, and the other detailed internal alterations to convert the building from a hotel into a private family house.

Preparing and presenting to the panel

It is quite common for people to feel nervous about these types of interview. However, this was not my experience: I felt well prepared and the interview was conducted virtually so I was able to speak from the comfort of my own home.

I prepared for the interview in the same way I would have a presentation for a client. I also worked on improving my presentation skills and spoke to colleagues who had been accredited.

My main aim was to demonstrate through the presentation my level of competency, knowledge and experience. I did so by frequently cross-referencing examples of previous projects I had worked on, not only my case studies.

The presentation must have been successful because the panel accredited me.

How the accreditation supports my work

It is understandable that owners of historic buildings in need of remedial work would want to put their properties in the hands of the most qualified professionals. A safe way of doing so is to enlist the services of those who hold recognised credentials that accredit them as experts in conservation.

The RICS Building Conservation Accreditation plays a key role, therefore, as it is highly respected and widely recognised in the sector. Furthermore, most of the projects eligible for external funding require that the professionals leading them have the accreditation.

Lately I have been involved in a wide range of projects on historic buildings. For example, I recently produced a planned preventative maintenance programme for a prestigious private school, whose campus includes several listed buildings.

I have also conducted a detailed, stone-by-stone condition survey specified and procured the required remedial works for a Georgian building in Edinburgh which we are expecting to commence on site pretty soon hopefully. The information collected from this survey has been logged in a 3D scanned model of the building, which has been developed specifically for that purpose.

In Glasgow I assisted with the submission of applications for grant funding to carry out external fabric repairs to two historic tenements – the applications stipulated that the submission process had to be conducted by a conservation-accredited professional. Both applications were well received and funding for the repairs of the historic external fabric of these buildings has been granted.

The RICS Building Conservation Accreditation has helped me secure these kinds of project by assuring clients that I have the right skill set, knowledge and experience to conduct conservation work on their property.

Why become RICS accredited in building conservation?

-

Professional status – market yourself with use of an exclusive logo

-

Access to work – many funding bodies and owners of heritage assets prescribe or expect professionals to have accreditation

-

Recognition – clients and employers can be assured of your standards, maintained by a regulatory system of quality assurance

-

Promotion – your details are listed on the RICS website

-

Support and networking – you have access as an accredited member to the Building Conservation Forum

Find out more about the RICS Building Conservation Accreditation