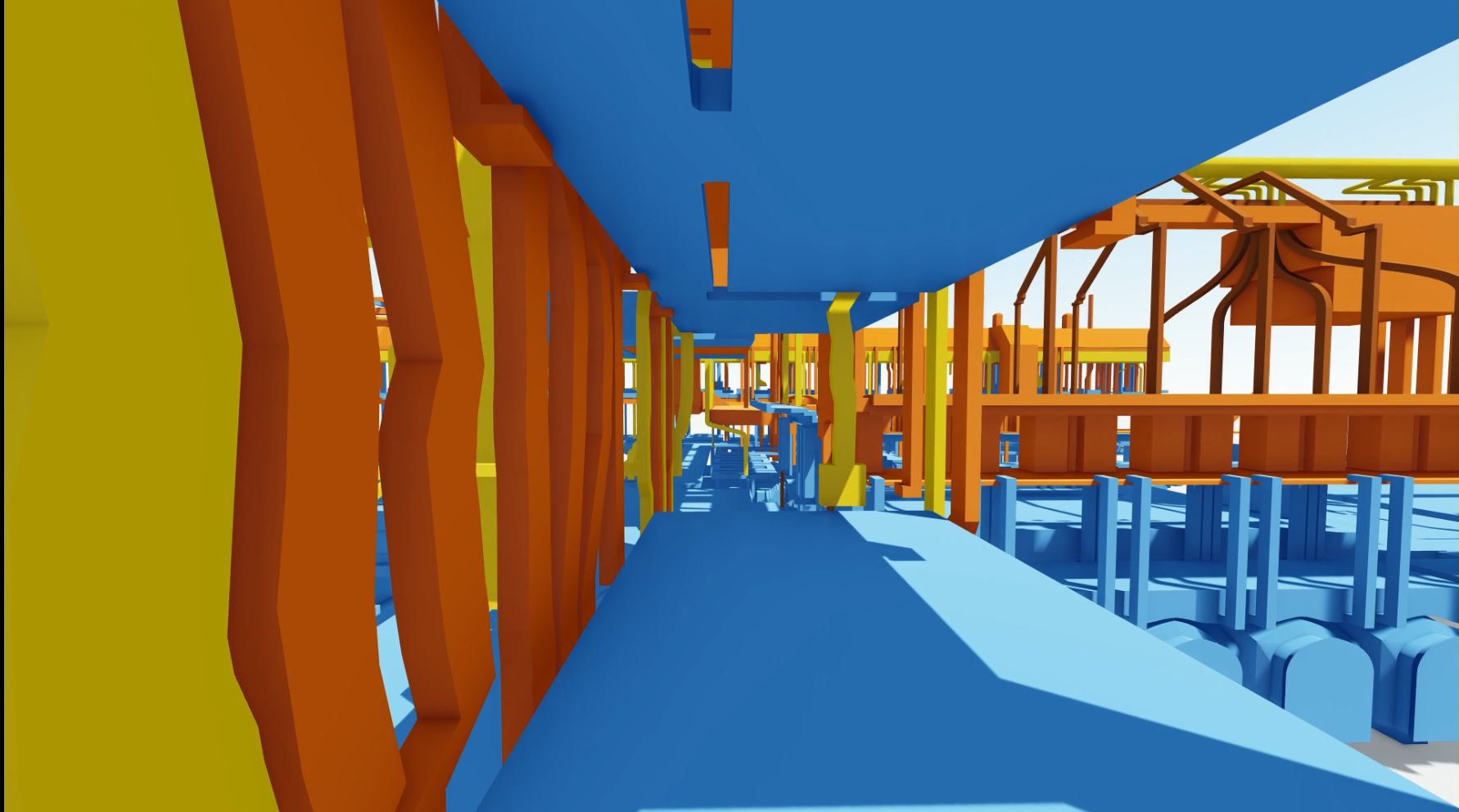

View of the voids seen from a corridor leading into the House of Lords

The Palace of Westminster is home to one of the busiest and most historic parliamentary institutions in the world, but after decades of under-investment, it is in a very poor and dangerous condition. Today the building is deteriorating faster than it can be repaired, and the longer the essential works are delayed, the greater the risk of a sudden catastrophic failure from fire, flooding or stone fall.

Most of the physical restoration work won’t start until the mid-2020s, so at the moment there are relatively few boots on the ground, but we are making progress with a raft of surveys and investigations so that we can much better assess the building’s condition.

Based on everything we know so far, and from initial studies of the Palace, we know the building is in desperate need of major renovation. But record keeping over the centuries has been poor and there are many areas in the Palace that we simply don’t know enough about.

The surveys we’re carrying out and those pencilled in for the forthcoming RIBA plan of work stages, will be much more comprehensive than anything that has gone before, and will be a huge part of addressing the gaps in our knowledge of the building. While on-site investigations have been paused because of COVID-19 restrictions, we are looking forward to resuming soon.

The programme has a strong data-driven approach. There is a vast amount of information available, both from new research and from the historical and past studies that are still accessible. These studies were undertaken by different parties for different purposes but are equally important to better understand the building. Our aim is to ensure all the information, already existing and in the future, is collected and held centrally.

Core surveys

As part of the RIBA Stage 1 plan of works, we identified 30 core surveys that are key to the future designs of the building; this ambitious programme of surveys got underway in 2019. It included desktop surveys on subjects ranging from air quality, flood risk, car parking, and soil contamination; to hidden voids and concrete structures. In addition, there were more intrusive investigations, which involved teams on site that spanned logistics, vehicle movement, resilience of windows and thermographic performance.

RIBA stage 1 also included the pilot area surveys. These were investigations on the structural make-up of the walls, floors and ceilings from rooms comprised within two selected areas of the Palace; from basement through to roof level, using a combination of techniques, primarily visual examinations and impulse radar.

To give a sense of the scale of this job – which covered only ten percent of the total building – it lasted six months and involved accessing nearly 150 areas of the building, taking over 170 scans, as well as moving and replacing over 200 pieces of artwork, and 1,900 hard back books.

Thanks to this extensive investigation, we now have a much more detailed picture of the likely form of construction across the entire Palace. It also helped us validate some of the earlier desktop surveys that had been carried out. In due course, we will have to carry out similar studies on the entire building.

BIM modelling

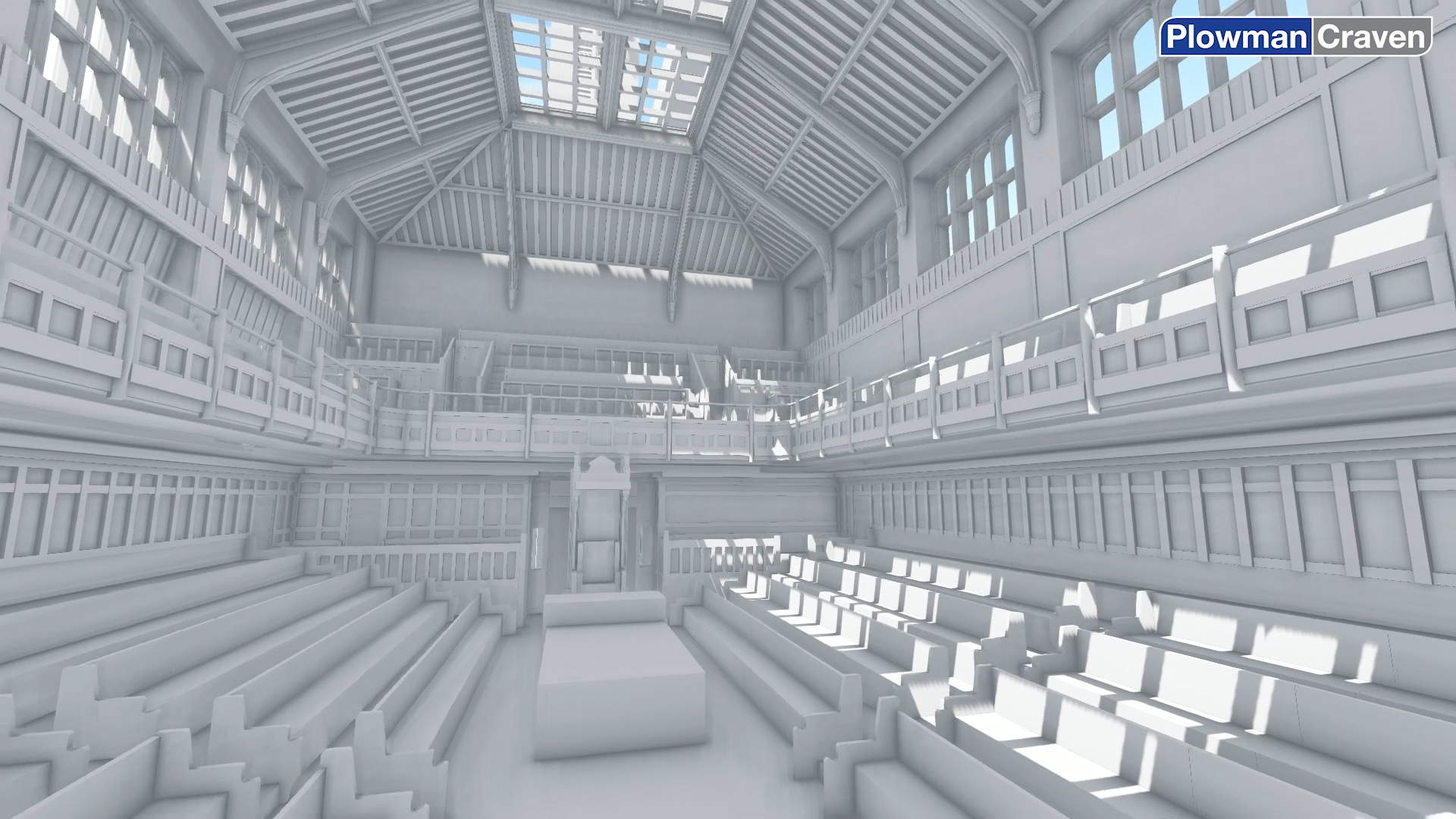

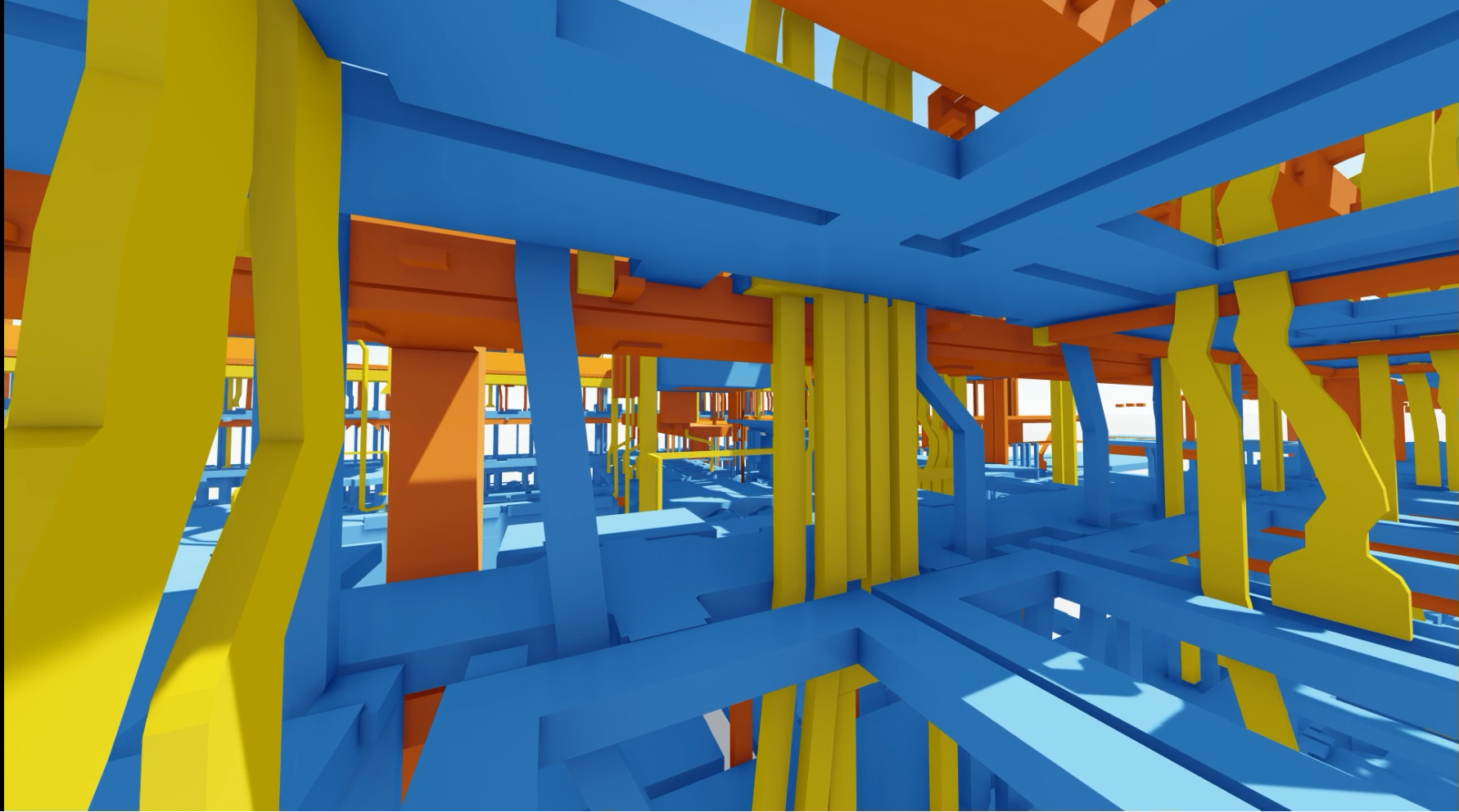

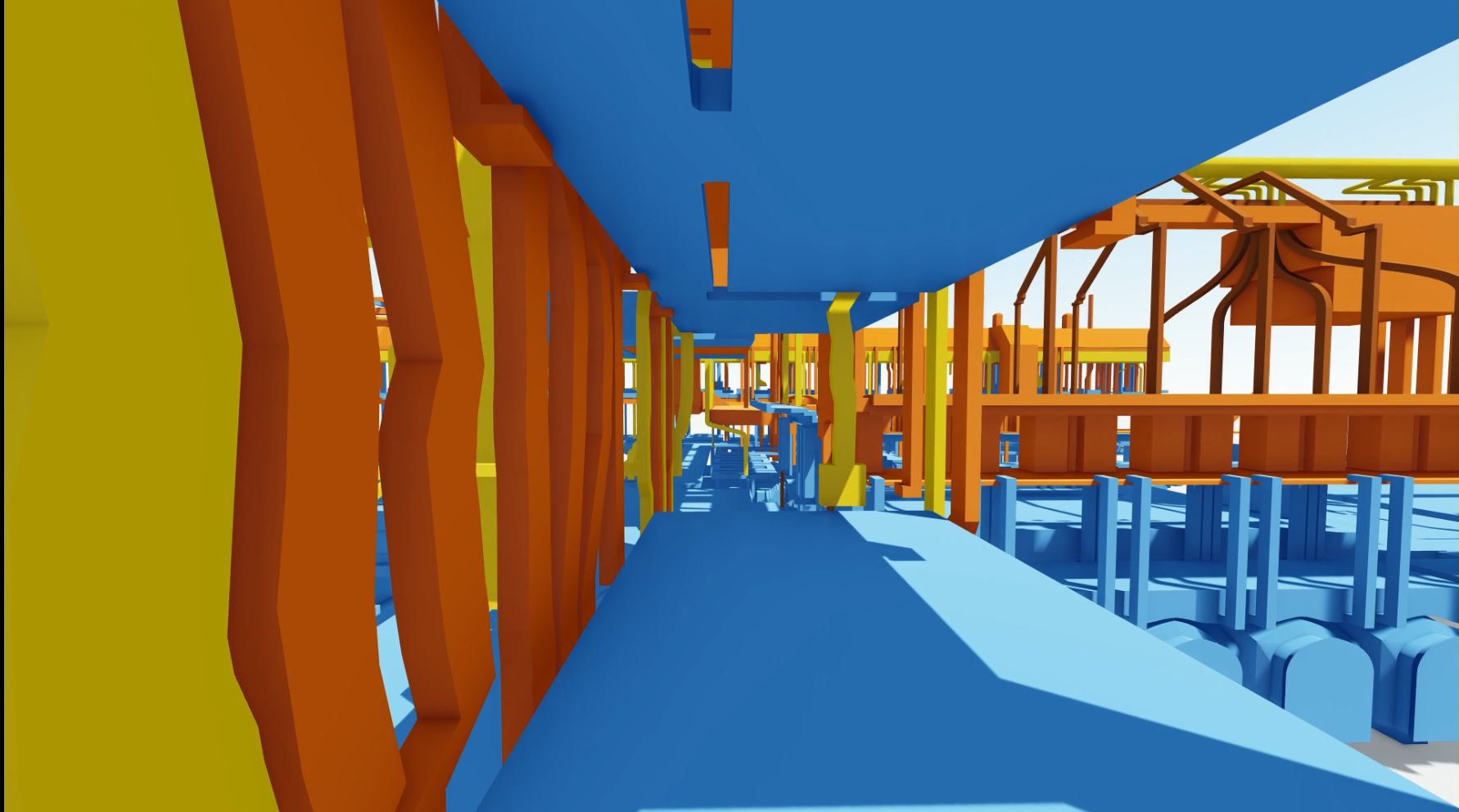

One of the earliest pieces of survey work that the programme has been delivering, and continues to improve upon, is our BIM modelling. We believe we have created one of the biggest single-building 3D models in existence, and that it is the world’s largest heritage 3D BIM model ever created.

The Palace has over 90,000m2 of internal area, and the BIM model has taken just under two years to complete, incorporating intense site presence and an average of 8 to 10 modellers working simultaneously.

It has been a challenging process as it involved surveying an existing heritage building with very complex architectural features. Furthermore, we needed to model many elements of the Palace at a high level of detail, but especially for facades and important architectural features, such as wood panelling, vaulted ceilings, and Victorian-era shaped windows and doors. Extra difficulties arose from the curved soffits and the pointed Gothic arches, confined spaces, voids and ventilation systems, buried drainage, inaccessible roof areas, as well as the presence of asbestos present across the building.

The BIM modelling has been a huge undertaking for the programme; in its first phase the accessible spaces and circulation routes in the Palace were 3D Modelled based on accurate laser survey information. In the subsequent phases, the voids and inaccessible spaces were based on exhaustive historical information cross-referenced with site investigations. It’s worth noting that the voids volume, attributed to the Victorian ventilation systems, is estimated to be a third of the whole of the Palace of Westminster, so a lot of the building’s volume remains inaccessible and has not yet been surveyed.

To tackle this issue, we have created a 3D Model of these areas with many of them forming part of the original ventilation systems. This model is based on years of detailed information gathering and complex analysis in a landmark research project led by Dr Henrik Schoenefeldt, Professor at Kent School of Architecture. In the next phase, a targeted approach will be implemented to survey the most relevant voids within the building and to obtain millimetric accuracy on the information.

Windows

Another early investigation was carried out into the condition and overall makeup of all the windows in the Palace, which number in the thousands. A combination of previously held data, floorplans, and Truview image records were used to drastically reduce site presence and as a first approach for grouping windows into categories, ahead of the site survey. Taking into consideration window and pane size, frame type, glazing thickness and type, the investigation found that the building has over 60 different types of window.

The volume of surveys and sheer size of the building is not the only challenge to this programme of work. The fact that the building is Grade I listed means that there is an added layer of complexity. This means that the survey work must, at all times, be sensitive to the historic and unique fabric of the building. So, as the teams go about their general work investigating the size of window apertures, or thickness of walls, they need to factor in the age and historical importance of every millimetre of the building and its unique contents

COVID-19

The Palace restoration has also had to adjust to the knock-on effects of COVID-19. Like many workplaces around the UK, the outbreak forced staff to work from home and to adapt to a new way of working. While there has been an impact to the survey work, given that much of it needs to be on-site, the proportion of surveys that had to be paused were thankfully small. In fact, given that we had completed many of the RIBA 1 surveys and were in the planning stages for RIBA 2 surveys, the timing of the outbreak of the virus could have had a much more detrimental effect than it did.

Currently the programme is scoping many of the RIBA 2 surveys and will continue undertaking desktop studies that will inform future site investigations. A challenge unique to the Palace of Westminster is the nature of the work that goes on within its walls. The team is not surveying an empty building, but an incredibly busy one that sees over a million people pass through its doors every year. That’s because it’s both a working parliament and a tourist destination.

So, working around tour groups, accessing politicians’ offices, investigating debating chambers or working alongside the maintenance teams is a logistical challenge. Throw into the mix the unpredictability of snap elections, the moving date of state openings, or the potential recall of parliament at two days’ notice, and you have a real challenge for scheduling the programme of surveys.

Long supply chain

One area of complexity, which is not necessarily peculiar to parliament, is our long supply chain. We currently have a principal designer, BDP, providing architectural, structural and building design services. They have a suite of sub-consultants and contractors carrying out a variety of survey work and desktop studies.

The more site intrusive surveys are directly contracted to the employer and we currently use contracts available to parliament for those works. This will change as the two independent organisations, recently launched to oversee and deliver the restoration, will drive the procurement for future surveys and this will increase exponentially over the next few years.

The two organisations are the sponsor body which provides strategic direction, and the delivery authority which will carry out the works. This is a hugely positive development for the overall procurement strategy for the programme, since we can source contracts that are more tailored to our needs.

Among the anticipated RIBA Stage 2 plan of work surveys, which are expected to take at least 18 months to carry out, are more compartmentation assessments for crucial fire safety planning, air quality assessments, and archaeological and ecology surveys. But as a Grade I listed building, with parts that date back to the 11th century, there are also a few investigations and surveys that you simply don’t find on any other job.

"It has been a challenging process because it was based on an existing heritage building with very complex architectural features"

Perhaps the survey which best highlights the unusual and unique nature of the building will be the assessment of the still working sewage ejector system which dates back to 1888. Despite the historic and unique nature of this corner of the Palace, this particular survey will still use twenty-first-century methods to capture the relevant data and inform any future designs.

It is an amazing privilege to work on the restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster, knowing that we are part of history in the making. It is a building like no other and carrying out these investigations is a job like no other.

Related competencies: BIM management, Data management, Inspection, Legal/regulatory compliance

The first article in this series can be found here.