Wrought iron gate of Dunrobin Castle in the Highland area of Scotland

There are few historic buildings which do not have associated ironwork of some kind, from the iron frames of 19th-century public and commercial buildings to gates, railings, hinges and door furniture.

Most surviving iron can be restored, although current conservation standards require the use of appropriate methods and materials where repairs or replacements are needed.

Leaving aside cast iron, the focus here will be the other most frequently found historic metal in the UK: wrought iron.

Composition helps prevent corrosion

Wrought iron – perhaps the most significant metal in the development of human technology – can be divided into two distinct types: charcoal and puddled.

The history of its use is broadly as follows:

-

charcoal iron – smelted using charcoal as fuel, used up to the end of the 18th century

-

puddled iron – made by the puddling process using coal as fuel, used from 1800 until the early 20th century

-

mild steel – much more highly refined, used from approximately 1870 up to the present.

From observation in the field, it appears that the older the type of iron, the better it resists corrosion; charcoal iron is better than puddled iron in this respect, for example. Curiously, then, the older the wrought ironwork, often the better can be its condition.

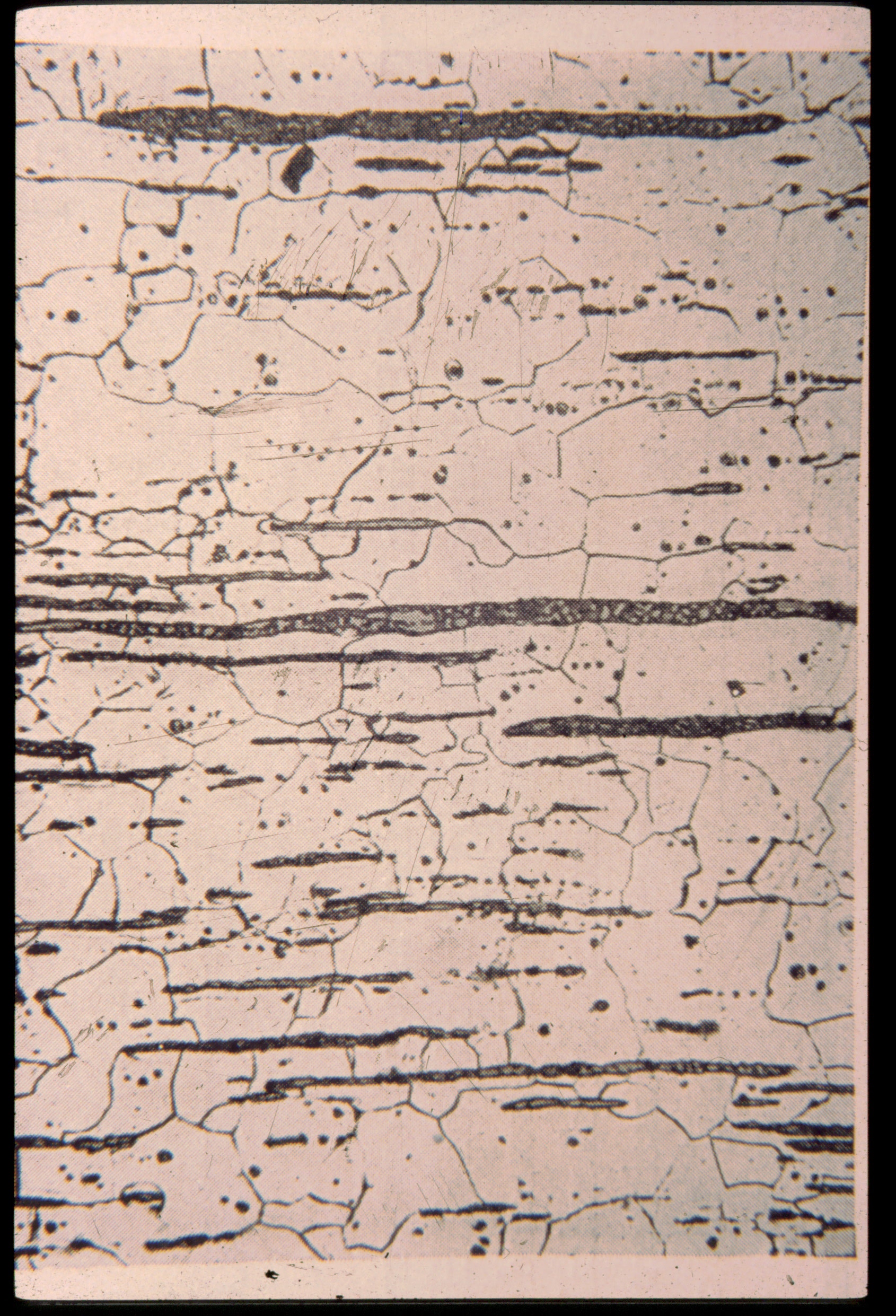

The wrought irons – charcoal and puddled – perform very well in normal weathering conditions, which in the UK has often meant a rather acidic environment due to industrial pollution. This is owing to the presence of fibres or strands of slag, which is a glassy material included during the manufacturing process that captures rather than refines out impurities.

More highly refined materials such as mild steel and pure iron corrode very rapidly in comparison because they lack the fibres of slag.

There are two mechanisms at work here. First, being glass-like, slags do not readily corrode and their presence on the surface slows the overall process of corrosion by inhibiting the flow of electrons (which cause corrosion) within the surface layer – they make up perhaps as much as 5% of the total composition of the wrought iron.

Second, the grain of the iron creates a rough surface that interlocks with any oxide layer – be it mill scale or rust – and prevents corrosion, with the oxide staying in place and protecting the iron.

Replacement component in puddled iron, 2015 © Topp and Co Limited

Union chain bridge – a source of wrought iron © Topp and Co Limited

Durability does not excuse poor maintenance

Notwithstanding conservation standards that enforce the use of original or near-original materials for repair, the properties of wrought iron do make it better than the alternatives of mild steel or pure iron in terms of performance. This raises several questions.

First, if iron is so durable, why do pieces of it end up in the workshop in need of repair? Nine times out of ten the answer is maintenance, or lack thereof.

All objects exposed to the elements require an appropriate level of attention. For example, the wrought iron gates to Buckingham Palace have had a rigorous regime of painting since they were installed more than a century ago, and are therefore in superb condition.

Conserving precious ironwork therefore demands a maintenance programme of this kind, even though it seems to be commonly assumed that it will look after itself until the next major refurbishment.

A further question relates to the availability of puddled wrought iron to use in repairs as its manufacture ceased in 1975. This was due to a decline in materials for traditional blacksmithing work as the market for ferrous metals in industry had moved on, as did the development of modern fabrication techniques which are not as suited to wrought iron as mild steel. This caused a general relaxation of standards.

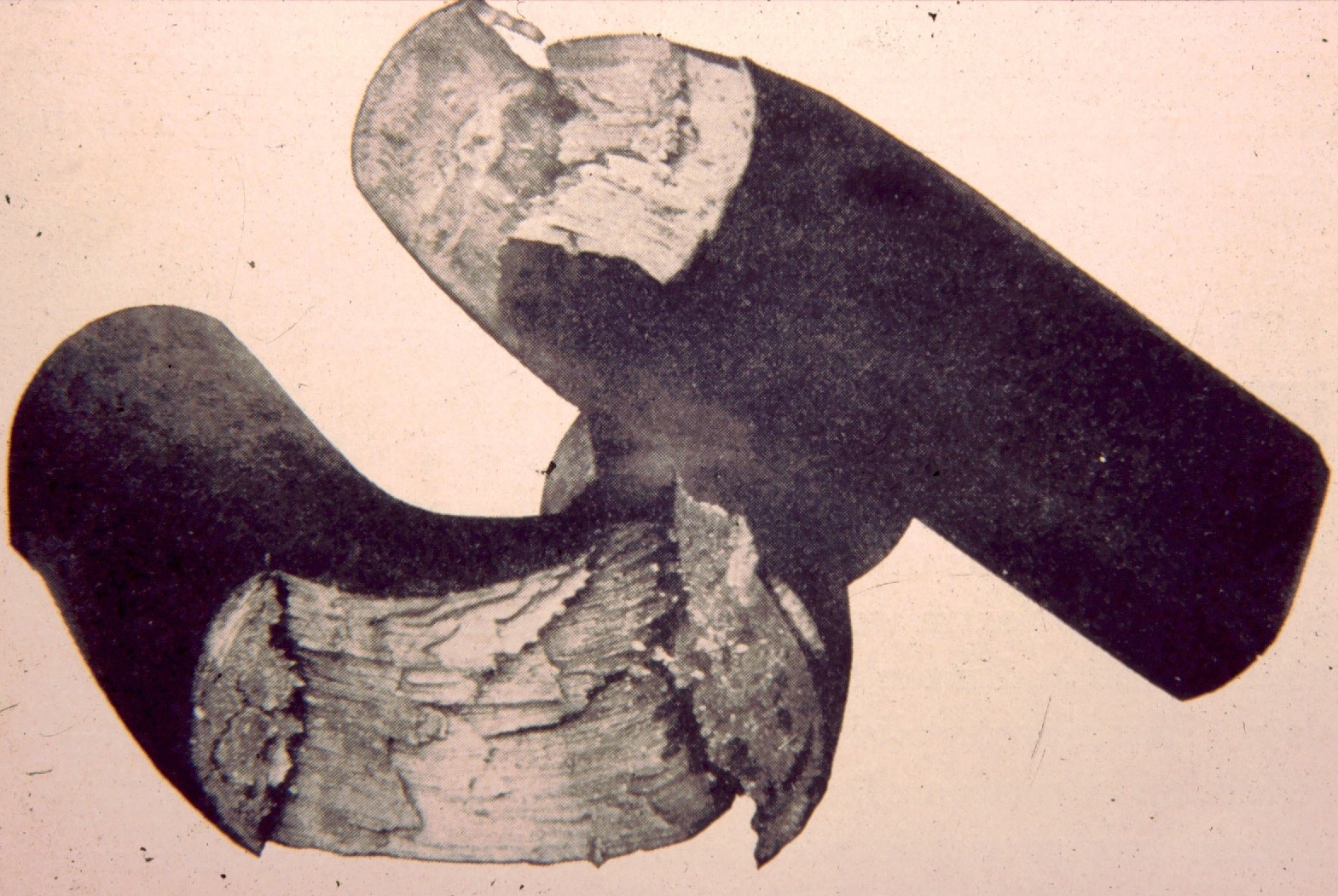

Nick bend test, puddled iron © Topp and Co Limited

Okeover 1717 charcoal iron still showing good condition © Topp and Co Limited

Demand and decline

Current and future supplies of wrought iron will have to come from recycling ancient material. Recent sources have included demolished structures such as bridges and gasholders, as well as heavy anchor chain.

Heavy wrought iron chain (up to three-and-a-half-inch square section material) is occasionally available on the scrap market. This has been made redundant by its replacement with similar chain in cast steel. Some wrought iron chain remains in service which may eventually find its way on to the market.

In the global context, there must be thousands of tons of heavy wrought iron chain abandoned on the sea bed owing to its long history in shipping. As with all specialist metals, its recovery and processing come at a cost; however, this would be more than justified considering the material's longevity.

Charcoal iron – often required in sheet form for making replacement leaf work – has also been successfully recycled by 'piling' small pieces of scrap derived from the offcuts of former refurbishment jobs.

Working successfully with wrought iron demands enhanced skill on the part of the smith, and the training required is another worthwhile investment in the long-term viability of such work.

Considering the amount of historic wrought ironwork in the UK, there is a case to be made for increased availability of training in conservation blacksmiths. The National Heritage Ironwork Group was established with this in mind, and is developing a system of accreditation for craftspeople who would like to be considered for contracts to repair important historical ironwork.

The most sustainable way to restore and conserve the ironwork of historic buildings is nevertheless to use long-lasting materials and to do it only once, entrusting each item to the care of a rigorous programme of maintenance.

Puddled iron cross-section © Topp and Co Limited

Chris Topp is founder of Topp and Co Ltd

Contact Topp and Co Ltd: Email

Related competencies include: Conservation and restoration