On 23 March this year the UK entered lockdown because of the COVID-19 pandemic, beginning a period of unprecedented challenge for the UK construction industry. The 2008 global financial crisis is the most recent comparable event in terms of scale and impact on industry productivity, output and financial stability. COVID-19, though, has introduced even greater challenges – halts or delays in production, wide-ranging health and safety implications and a threat to the continuity of supply of key goods and services.

The immediate risk to the construction industry supply chain was the requirement to close sites and pause the planning, development and delivery of projects. The impact of this risk was, and remains, potentially devastating for the many small to medium companies that comprise a substantial proportion of the supply chain. Halts in production had an immediate impact on cashflow and the solvency of suppliers.

To mitigate this risk in the UK public sector, the government published a series of Procurement Policy Notes (PPN) to protect at-risk suppliers and ensure, as far as possible, that normal contract delivery could continue once the pandemic was under control. PPN 02/20 of March 2020 and subsequent updates provided much-needed assurance to the supply chain that financial and other support was available. For instance, clients such as Network Rail and Sellafield Ltd introduced immediate payment terms and support payments for their critical suppliers.

Improved financial terms and accelerated payments have certainly been a lifeline to many suppliers and maintained the solvency of businesses and provided continuity of supply. However, COVID-19 presents a wider and more complex range of risks to the industry’s supply chain. It is not enough to manage the impact of the risk; asset owners and operators now need to understand how resilient their critical suppliers are to future shocks on the scale of COVID-19.

“It is not enough to manage the impact of the risk; asset owners and operators now need to understand how resilient their critical suppliers are to future shocks on the scale of COVID-19”

Why is resilience important?

The US Presidential Policy Directive 21 defines resilience as the ‘ability to prepare for and adapt to changing conditions and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions’.

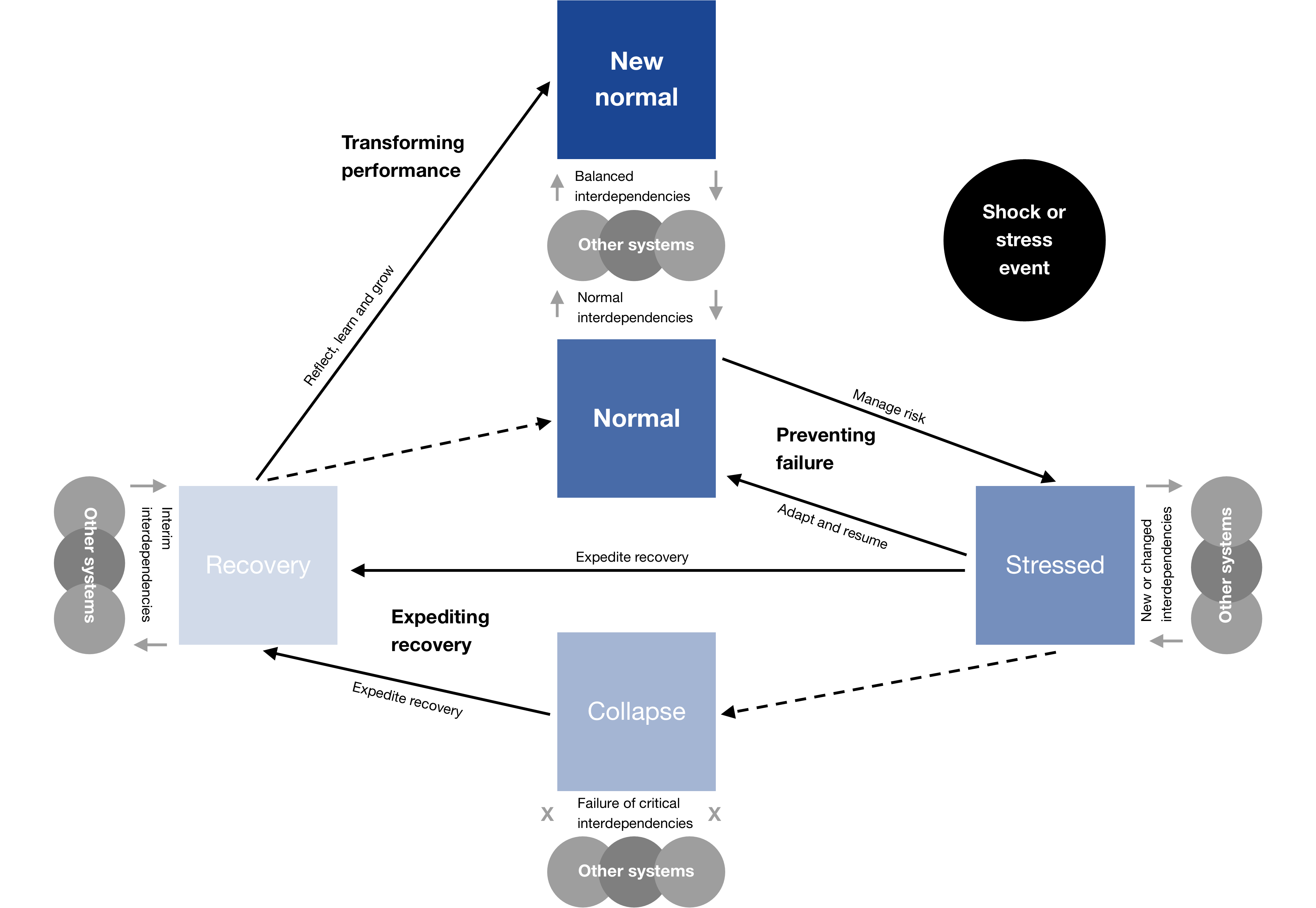

From a whole-system perspective, resilience can take one or a combination of three pathways.

-

Preventing failure:

ensuring systems can withstand the direct and indirect impact of disasters.

-

Expediting recovery:

supporting systems to become functional as soon as possible after stress or collapse.

-

Transforming performance:

working towards a new and improved state.

When any system goes into shock, the immediate concern is to manage and adapt to the stresses to prevent a collapse, as shown in the below figure. Expediting recovery is critical to enable a return either to the normal condition or to transform performance and realise an improvement. Resilient organisations are agile and proactive and plan for the longer term. In a volatile world of increasingly large-scale and unpredictable risk events, such organisations may also benefit from a competitive advantage.

Managing and adapting to shocks and stresses to prevent collapse

- the impact of the pandemic on the health, safety and wellbeing of employees

- the availability of key workers and operatives to maintain service provision under lockdown conditions

- the structure of the extended supply chain for goods and services

- the availability of key materials, goods and services, both in the UK and globally

- levels of inventory held for key materials and goods

- warehousing locations and their accessibility

- an understanding of ports of entry and any restrictions in place

- logistics and transport flow from point of origin to point of use

- the management actions being taken to adapt in terms of leadership and governance.

In this context, understanding resilience requires a structured appraisal methodology that can be applied both to critical suppliers and to develop the data and insights to manage risk effectively.

Resilience analysis

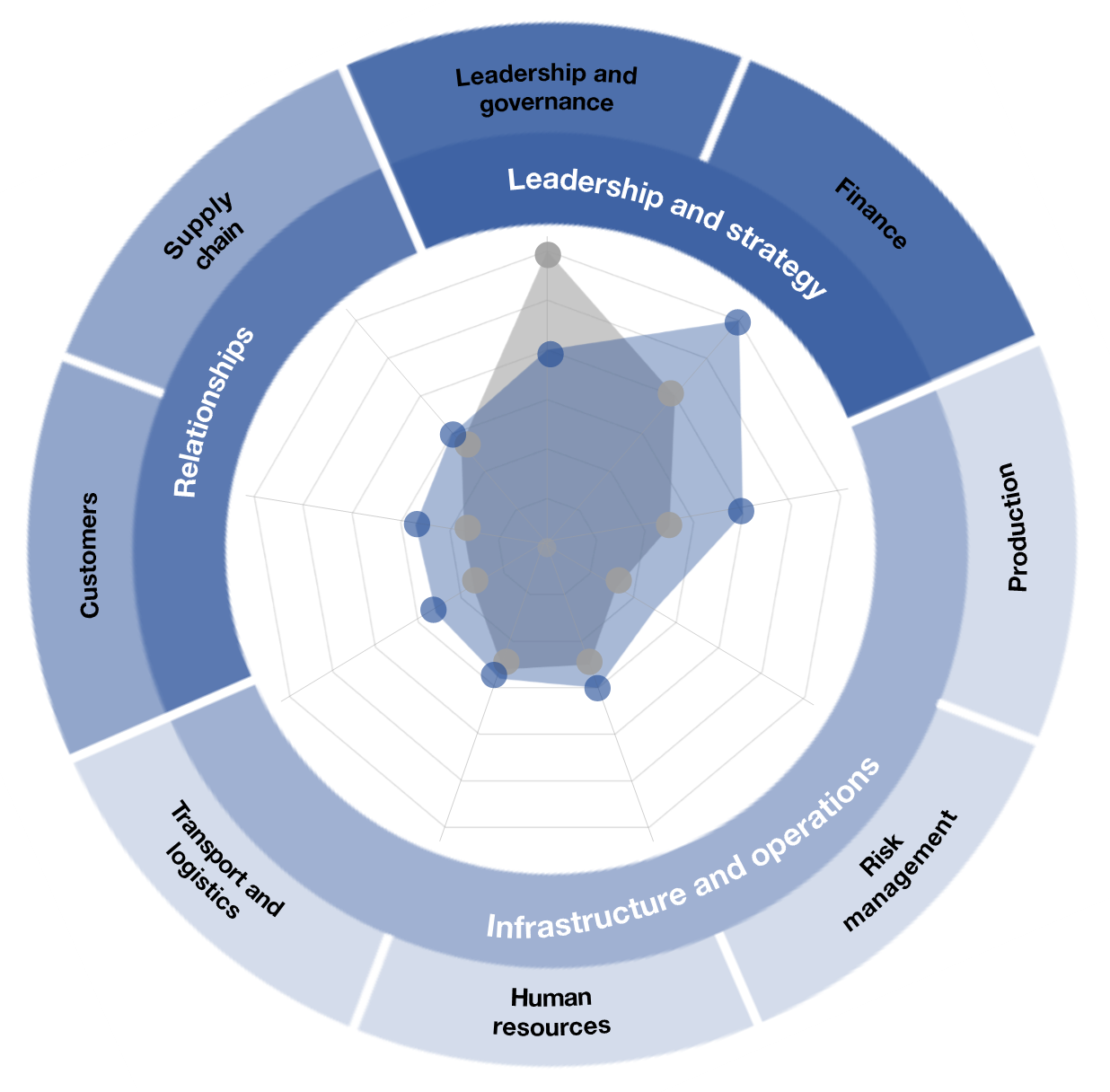

Using an organisational analysis model is a starting point for building an understanding of supplier resilience. It has the advantage of viewing a supplier from a whole system perspective, including a wide number of factors that contribute to a resilient business. Understanding each of these factors considers a broader framework than relying on financial stability or solvency alone.

The above example illustrates the model aligned to three core categories of leadership and strategy, infrastructure and operations and relationships. The sub-categories relating to resilience include:

- leadership and governance

- finance

- production

- risk management

- human resources

- transport and logistics

- customers

- supply chain.

Key to the approach is structuring the response ranges to build a gap analysis, as seen in the figure below. For example, the supply chain risk presented by the pandemic requires most businesses to either implement an existing business continuity plan or to develop and implement a strategy at pace. The resilience risk – or demand – is high in this instance and acts as a baseline measure to measure the supply chain’s position – or resilience capacity. The variance between resilience demand and capacity produces a gap analysis.

Resilience gap analysis showing resilience demand in grey and resilience capacity in blue

As shown above, the resilience demand in respect of leadership and governance is high whereas the supply chain capacity is lower, indicating a gap and potential risk to supply that may require management or intervention. Conversely, the supplier scores highly in financial capacity versus a lower resilience demand, indicating the supplier has the necessary strategies in place to manage risk.

When combined with existing supply chain risk management tools and intelligence, greater insight into supply chain resilience can be obtained. It is important that a collaborative approach is taken to applying these tools. Understanding the resilience of the supply chain can benefit both customers and suppliers by identifying potential risk and helping prevent failure, expedite recovery and enhance performance in the longer term.

Data gathered from resilience analysis should always follow good practice in data confidentiality and security. Resilience questionnaires should be issued on a secure platform and several systems exist to structure the information requests and to collate the responses in a central secure database.

Presenting this information graphically, using tools such as Power BI, can condense complex data into easily interpreted graphics. Good examples can be found in sources such as the City Resilience Index – developed by Arup with support from the Rockefeller Foundation – that provides a comprehensive, technically robust, globally applicable basis for measuring city resilience.

“Understanding the resilience of the supply chain can benefit both customers and suppliers by identifying potential risk and helping prevent failure, expedite recovery and enhance performance in the longer term”

Planning for the long term

Construction supply chains have evolved over many years, adopting the efficient management systems seen in the manufacturing and production sectors. This ‘just-in-time’ approach requires a highly responsive supply chain that reduces lead times and levels of inventory held, optimising production and reducing costs. COVID-19 has illustrated the vulnerability of such lean management techniques, an excellent example being the availability of low-cost supplies of PPE. Following the outbreak, a global spike in demand made the supply and delivery of simple, low-cost items such as nitrile gloves a critical issue.

The COVID-19 pandemic can also be characterised as an asymmetric threat to supply chains in that it affects organisations and their lines of supply in different ways. In the future we will need to consider the resilience of supply chains both in the event of future outbreaks but also when concurrent risks – such as those arising from climate change – occur.

Long-term resilience building and improvement requires a process of monitoring, progress reporting and learning development. This process of developing resilience should involve continuous engagement, assessment development, capacity building and learning, so that resilience becomes embedded in the culture of an organisation and forms the basis of strategic decisions.

Measuring and understanding resilience in supply chains is a relatively new area of expertise. However, there are several free resources available, through the Rockefeller Foundation, and Resilience Shift, a collaboration between Lloyd’s Register and Arup.

Quantity surveyors and project managers have interesting and important roles to play in creating more resilient supply chains for our clients. We make key decisions in the development life cycle, are responsible for managing a wide range of risk and develop long-term, collaborative relationships with suppliers. In the future, both professions can benefit from understanding more about the structure and resilience of the construction supply chain to inform the professional advice they provide.

“Long-term resilience building and improvement requires a process of monitoring, progress reporting and learning development”