In the wake of Grenfell, a key topic of both parliamentary and industry scrutiny in the UK was the lessons that could be learned from this tragic event. In the House of Commons debate following the Phase 1 Report, for example, politicians of all parties repeatedly noted that lessons had to be learned from Grenfell to prevent it from happening again.

However, it was also noted that learning the lessons would not be simple: one participant suggested that the government’s ideological preconceptions and vested interests might skew the lessons learned process; another noted the fact that the lessons had clearly not been learned from the Lakanal House fire; and another pointed to the significant tension between allowing the time to complete a thorough review into Grenfell and the need to take immediate action to address existing safety issues in residential buildings.

A particularly interesting viewpoint was expressed by Emma Maier, editor-in-chief of Inside Housing: “It is clear that many of the lessons have not been learned … At times it has been difficult to get traction. The understandable focus on culpability and blame sends organisations into lockdown. It can get in the way of finding out what went wrong and sharing crucial details that could improve safety in the future… The Lakanal inquiry took four years, the court case took eight. The sad paradox is that the desire to gain understanding can make it harder to learn the lessons to prevent further tragedy.”

The themes that emerge from Grenfell are a microcosm of the wider topic of lessons learned in general. While it is universally acknowledged that lessons learned are of intrinsic value and that a lessons learned workshop should be a key part of virtually any project, it is less clear how a project manager is to ensure that lessons are best captured, disseminated, and – most importantly – actually learned from and used to drive real improvement.

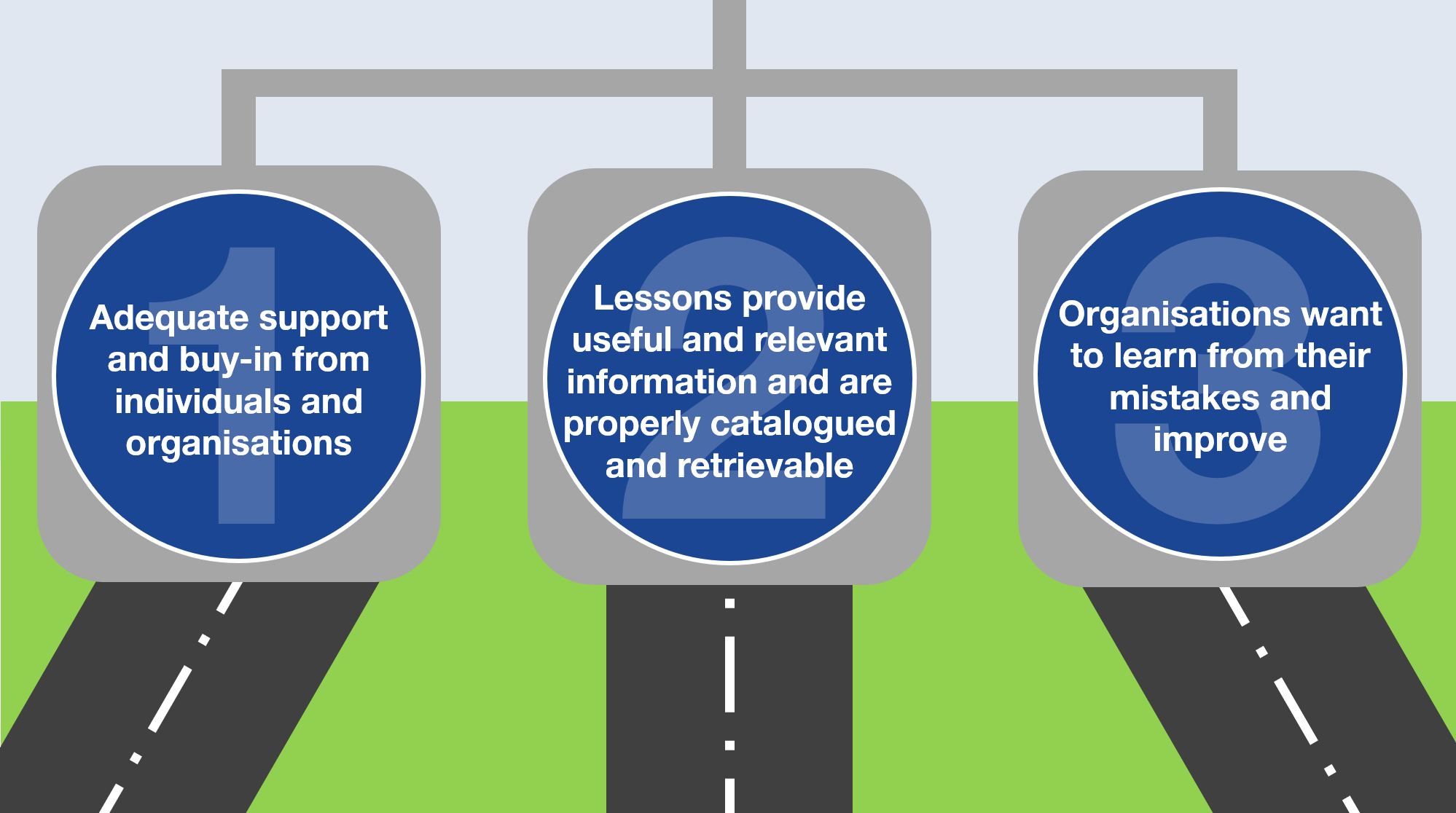

I believe there are three checkpoints that a specific lesson has to pass through in order to ensure that it can be effectively learned and used.

Checkpoint 1: Adequate support and buy-in from individuals and organisations

This first checkpoint is right at the beginning of the lessons learned journey, and the requirement for passage through it is simply that there is sufficient buy-in to the very concept of learning lessons from projects.

While this might appear to be a relatively low threshold for entry, it is clear that many projects are not critically assessed with the objective of understanding and capturing the most important lessons. The RICS Lessons Learned guidance note divides the reasons for this into individual and organisational factors.

- project stakeholders considering the process a waste of time

- being fearful of being punished for admitting to a mistake

- being more interested in self-promotion in front of the client than a deep dive into project failings.

- having a culture that is not interested in learning

- having a culture that is characterised by short-termism and a focus on either conflict avoidance or finger pointing

- not having the resources to fully support the lessons learned process.

Since projects are often thought of as unique endeavours, there can be a tendency to get lost in their exceptionalism and believe that there is little which can be applied outside of the specific context of the project.

This viewpoint can be amplified if an organisation is participating in a project that is considered a one-off. What is the point of doing a thorough lessons learned review for a small bridge project procured under an NEC form of contract, for example, when the vast majority of a firm’s work is fit-out work procured under JCT?

Often, shortly after contractual completion most members of a project team are immediately redeployed on to their next assignment. It can be extremely difficult to get either attendance or sustained engagement in the lessons learned process from individuals who are required to hit the ground running on their new project.

Unfortunately, failure to pass through the first checkpoint means that either lessons are not captured in the first place or, if they are, the process takes place in an environment which will not produce optimal results. There is a serious risk that the lessons learned workshop might be rushed, poorly attended, and undertaken in the manner of a blame game, rather than a collaborative and comprehensive effort to genuinely understand how to improve performance.

However, there are practical things which project managers can do to ensure that the lessons learned process has the best chance of obtaining useful outputs.

From the outset, the project manager can seek to ensure that adequate provisions for lessons learned reviews are allowed for at the start and end of a project and periodically throughout its lifecycle. Consultants’ appointments and contractors’ prelims should stipulate engagement in specific lessons learned activities, and they should also be clearly referenced in both the programme and in the project execution plan. Moreover, whatever the level of formal buy-in to the lessons learned process, the project manager will also need to use all of their stakeholder management, communication and conflict avoidance skills to ensure that the right people meaningfully participate in lessons learned activities.

The project manager should also look to best practice guidance for conducting a lessons learned session. For instance, the RICS’ guidance note provides common sense instructions for convening a workshop, including clearly communicating the expectations and benefits to potential participants, collecting a list of issues to help create a thematic framework, setting clear rules of engagement on the day, and the use of an independent facilitator where possible. This guidance note also provides some sample slides which outline what the workshop is and is not, its rules and the expected inputs and outputs.

“Failure to pass through the first checkpoint means that either lessons are not captured in the first place or, if they are, the process takes place in an environment which will not produce optimal results”

Checkpoint 2: Lessons provide useful and relevant information and are properly catalogued and retrievable

Once a lesson has been comprehensively discussed by the relevant project team members, the next checkpoint is to ensure that it is properly documented and stored so that it can be easily accessed when it is relevant to a future project.

In an article for the Project Management Institute, Sandra F. Rowe and Sharon Sikes suggested the use of several techniques to help achieve this.

- project survey forms with standardised categories to structure lessons learned reports

- lessons learned templates which use consistent fields such as category, lesson learned, action taken, reasoning for action taken, root cause and key words

- the use of a dedicated lessons learned repository at an organisational level.

This focus on a systematic approach to cataloguing lessons learning in order to facilitate accessibility and retrievability is also echoed by the Association for Project Management. In its Body of Knowledge (6th edition), it recommends the following approach for dealing with lessons learned.

- establishing ownership of knowledge management and the systems that support it;

- implementing mechanisms for finding external knowledge and making it relevant internally;

- identification and extraction of key lessons from projects, programmes and portfolios, including contextual information;

- structuring and storing knowledge so that it can be accessed easily;

- maintenance of the knowledge repository to ensure it is up to date;

- embedding processes that ensure knowledge is used effectively.”

Martin Paver, a specialist in data-centric project management, has pulled together a database of more than 10,000 lessons learned from a variety of sources, including National Audit Office reports, parliamentary reports, and Freedom of Information requests. Paver’s review of his database has led him to conclude that many of the lessons lack forensic insight, context and root cause analysis, that they are captured without using a standardised format, and that the focus is on process rather than outcomes.

They are also not stored in a way that provides efficient searchability and retrieval. For instance, when submitting a FOI request to the BBC for the assurance reports and lessons learned for 15 large recent projects, he was informed that the relevant documents “are held in a variety of ways and by significant numbers of BBC employees and third parties… It is estimated that completing these tasks could take 26 days to retrieve and compile the requested information”.

If it takes a major organisation 26 days to retrieve the lessons learned for recent and important projects, then the question can legitimately be asked of how these lessons are actually able to be learned. And this does not even factor in 2 other potential barriers.

The first of these is that – from a consultancy perspective at least – many clients insist on NDAs and confidentiality agreements, and this, along with the impact of GDPR, can have an effect on the quality of lessons learned, or at least make capturing a good lesson require significantly more effort. Some lessons learned reports may have to be cleansed of specific client details or personally identifiable information and have the contextual details removed in order to comply with framework agreements, service instructions and current legislation.

Second, even assuming that the lessons are properly categorised, tagged and stored in a repository where they can be easily accessed, the usefulness of the lessons are still highly dependent on their retrievability. For instance, if the lessons are simply saved in a large Excel sheet or as separate documents on a SharePoint site, then there is a very real danger that searching for common terms or keywords could – depending on the size of the database – bring up dozens or even hundreds of largely irrelevant results. The search functionality for these kinds of databases can be slow, non-intuitive and unable to prioritise the results to provide the requestor with the most useful lessons.

This was a very real issue experienced by NASA, which has a lessons learned database of almost 10m documents dating back over the past 60 years. The database historically used a PageRank algorithm which prioritised search results according to how frequently they had been accessed, and this meant that for one specific query a NASA engineer had to read through around 1,000 individual documents to see if they contained any relevant information.

NASA solved this problem by investing in new software to better visualise the correlations between various lessons learned in order to improve the relevance of the results. This drives home the point that it is very important for all construction industry organisations to evaluate their own lessons learned databases to ensure that the opportunity to retrieve relevant lessons is maximised. There are numerous ways of doing this – and a plethora of different digital applications that could be used – but the central objective has to be to avoid vital information being siloed away and forgotten.

Another key action that can be undertaken at an organisational level is to ensure that standardised tools and templates are used for the lessons learned process to ensure data consistency. Lessons learned resources should be included within project and programme management toolkits, and a key requirement for colleagues should be regular and accurate submission of lessons learned into a centralised repository.

At an individual level, the main requirement of the project manager is to ensure both that a lessons learned process is properly adhered to and that the lessons learned themselves contain enough detail, context and insight to truly benefit future projects. The project manager will need to use their motivational skills to try and get project stakeholders to buy-in to the lessons learned process and their analytical and communication skills to ensure that every lesson is robustly interrogated and presented in the most effective way possible.

“While it is clearly common sense that lessons should ideally be captured in a way that enhances their usefulness and stored in a way that maximises their retrievability, the reality appears to be quite far removed from this ideal”

Checkpoint 3: Organisations want to learn from their mistakes and improve

Assuming that an organisation has embedded a mature lessons learned process and maintains an accessible knowledge platform, and that individuals regularly and committedly participate in lessons learned reviews, then there is only one checkpoint left in the journey to ensuring that the most important lessons are actually learned and used. In many ways, however, this checkpoint is the most vital one of all. To gain passage through this checkpoint, organisations need to view the whole lessons learned process not just as a tick-box best practice exercise, but as an essential way of learning from their mistakes and achieving continuous improvement. They must want to learn from their lessons and to implement any required changes.

An interesting insight into the reluctance of many organisations to make the changes recommended by their lessons learned process is provided by Kevin Pollock’s report on interoperability in the emergency services. Pollock ultimately concluded that: “The consistency with which the same or similar issues have been raised by each of the inquiries is a cause for concern. It suggests that lessons identified from the events are not being learned to the extent that there is sufficient change in both policy and practice to prevent their repetition.

“[In the majority of lessons learned reviews] the doctrine and prescriptions are often structurally focused, proposing new procedures and systems. But the challenge is to ensure that in addition to the policy and procedures changing, there is a change in organisational culture and personal practices. Such changes in attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviours are more difficult to achieve and take longer to embed. However, failure to do so will result in the gathering of the same lessons which repeat past findings rather than identifying new issues to address and continuously improve the response framework.”

A 2018-19 audit into the London Fire Brigade found that: “The London Fire Brigade has clearly learned lessons from the Grenfell Tower incident. However, it has been slow to implement the changes needed, which is typical of the brigade’s approach to organisational change.” In this instance the organisation has the capability and resources to learn the lessons from Grenfell, but perhaps did not, at the time, have the required level of commitment to force through what might be complex, far-reaching and difficult changes.

Part of the solution for this might be for organisations to have dedicated resources for evaluating lessons learned, reporting trends and patterns, and ultimately either implementing the changes themselves or offering clear recommendations to those with decision-making authority. As Rowe and Sikes suggest: “… organisations need to dedicate a resource or resource(s) to begin the analysis of documented lessons learned. The purpose of the analysis is to identify actions that can be taken within the organisation to strengthen weak areas of knowledge and implementation during each project. This can be done through enhanced training of project managers and/or team members; this includes project sponsors and champions. It may mean added or improved procedures and processes.

“The person(s) tasked with analysis of an organisation’s lessons learned should be located at a level within the organisation that will enable the person(s) to implement approved solutions.”

Firms will also need to transform themselves into what Pollock terms a “learning organisation”. This type of organisation will “ensure that the lessons learned will result in changes to the organisational culture, norms and operating practices. These will be successfully embedded in the values and beliefs of the organisation and those who work in it.”

At an individual level, project managers can also have an impact in terms of fostering a culture receptive to learning from past experience and committed to continuous improvement. For instance, Paver recommends that positive lessons in particular should be shared widely within an organisation through the use of technical papers, lunch and learn sessions, campaigns and training, and by developing wiki content and videos. All of this can help nudge an organisation in the right direction.

“Organisations need to view the whole lessons learned process not just as a tick-box best practice exercise, but as an essential way of learning from their mistakes and achieving continuous improvement”

My experience of lessons learned

My own experience of the lessons learned process is varied. In some instances – and particularly when delivering successive projects on a framework – I have led comprehensive and collaborative workshops, captured important and relevant lessons, and been able to take these learnings into the next scheme to demonstrably improve project delivery. On occasion, however, and particularly when undertaking one-off projects, I have found that it has been very difficult to get stakeholders to buy into the lessons learned process, that the workshops have been both poorly attended and full of recriminations – particularly when something has gone wrong – and that the lessons learned report is issued and promptly forgotten about.

There are many reasons for this, but the stakes are so high in the construction industry that it is extremely unfortunate that the hard-won experience and insight accumulated by all construction professionals cannot be better leveraged to learn from our experiences and to improve quality, safety and efficiency across the industry.

Facilitating the journey of a lesson through the three proposed checkpoints is by no means an easy task, but it is a necessary one if construction industry professionals and organisations are to maximise their quality, safety and efficiency. The foregoing discussion outlines some of the potential barriers and possible solutions for ensuring that lessons are better learned and used, but this is just the tip of the iceberg in what is clearly a complex and multifaceted issue.

A useful next step would be an industry-wide review of the lessons learned from trying to implement a lessons learned culture, but in the interim I would be more than happy with a thoughtful debate on how to improve the effectiveness of the lessons learned process in the construction sector.

Josh Olsson MRICS is a project manager at Arcadis

Contact Josh: Email

Related competencies include: Leading projects, people and teams, Stakeholder management