Neurodiversity is an important topic of conversation across the built environment. It matters not only for social and ethical motives, but for two specific reasons that are fundamental to our profession.

First, workplaces in construction span both permanent offices and temporary sites that effectively become offices for many months, and sometimes years. Creating psychologically safe, sensory-aware and cognitively accessible environments supports productivity, reduces burnout and helps retain talent.

Second, when our industry understands and reflects the diversity of society, we're better equipped to design spaces that include everyone who uses them, rather than unintentionally excluding some individuals through assumption or oversight.

Our sector already employs a significant proportion of neurodivergent professionals, both formally diagnosed and self-identified.

A 2024 research report by the Association for Project Management found that 46% of project professionals in construction consider themselves neurodivergent, compared with 31% across all sectors.

In addition, an earlier 2023 report by the National Federation of Builders (NFB) found that around one in four construction workers identify as neurodiverse, and 17% have been formally diagnosed.

In other words, neurodiversity isn't a marginal concern in construction. However, the NFB report also found that 75% of construction workers say they were not asked about neurodiversity at the hiring or onboarding stages, which signals a lost opportunity to offer support or build understanding.

This gives us both an ethical obligation to support our people and a commercial imperative to harness the strengths that diverse colleagues bring.

Evidence is growing that the inclusion of neurodiverse colleagues in teams can improve project outcomes through innovation, attention to detail, lateral thinking and rigorous risk-based reasoning.

As chair of the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) committee at Bailey Partnership, a 200-person construction consultancy, I have spent much of the last year gathering internal data, mapping disability and neurodiversity representation across our workforce, and working to build support structures to empower colleagues.

Alongside chairing the committee, I lead our Chichester office and South Coast project management team. My day-to-day work includes engaging with colleagues, clients, contractors, consultants, supply chains and resident groups.

Chairing the committee alongside my everyday work has taught me that people process and communicate information in profoundly different ways, and that language, structure and clarity are vital to success.

What is neurodiversity?

Neurodiversity refers to natural variations in the human brain, encompassing autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette syndrome and other cognitive profiles. It recognises that neurological differences should be acknowledged and respected.

Neurodivergent describes people whose cognitive functioning differs from societal norms. Neurotypical describes cognitive functioning aligned with those norms.

As someone with ADHD, I've experienced both the benefits and the friction it can bring. Neurodiversity can bring valuable strengths: pattern recognition, visual problem-solving, deep focus, creativity, hyper-specific expertise and novel problem-framing.

Challenges can include sensory overload, difficulty with ambiguous tasks, working memory limitations, or fatigue from masking, which is a process where individuals moderate their behaviour in an attempt to fit into social norms.

A one-size-fits-all approach does not work in modern project environments. Instead, tailoring communication and workflow to individual colleague's strengths can unlock performance.

Embedding EDI in practice: how our committee works

The EDI committee was created as part of a conscious decision by Bailey Partnership's leadership to strengthen our culture and improve staff well-being, while responding to clients' increasing expectations around inclusion and social responsibility.

It has united colleagues across our offices and professional disciplines who are passionate about change, including project managers, quantity surveyors, building surveyors, architects, engineers and others.

Coming into the committee chair role, I drew on the skills and methods I've developed as an RICS chartered project manager to understand our baseline and shape our direction.

My first step was to understand our starting point – assessing where we were, what strengths we already had and where the gaps lay. From there, I drafted our manifesto: a clear vision, shared values and a set of SMART objectives.

Together, the committee established a concise constitution outlining member responsibilities, time commitments and meeting cadence, giving the committee structure alongside enthusiasm.

Our strategic priorities include the following.

- Data gathering – understanding who we are and where the gaps are.

- Inclusive design – embedding inclusion in both physical and digital spaces.

- Onboarding and training – ensuring accessibility from day one.

- Progression – removing barriers to advancement.

- Recruitment – attracting and retaining diverse talent.

- Well-being – fostering psychological safety and work–life balance.

Neurodiversity cuts across every one of these priorities. It shapes how we write job descriptions – using plain language and clear essential criteria – and how we structure interviews, such as offering flexible formats or additional time where needed.

It influences the way we communicate tasks, promoting clarity over ambiguity, as well as how we manage teams to prevent overload and burnout.

It also affects the tools we choose, in order to ensure our software is accessible, and even how we design our offices, where sensory considerations can make a significant difference to comfort and performance.

We have learned that consistency matters. Adjustments cannot rely on individual manager's discretion, nor on employees feeling safe enough to start those conversations.

The goal is to create systemic inclusion: an environment where good practice is built in.

This year, we launched our first firm-wide diversity questionnaire at Bailey Partnership. Before distribution, we focused heavily on building psychological safety and explaining the purpose clearly; this was not about monitoring individuals, but about understanding our workforce at a collective level.

The questionnaire was fully anonymous, designed to provide a current baseline for the firm and complemented by our standard process of one-to-one conversations between line managers and staff members.

These individual conversations allowed us to provide support where needed, while the questionnaire helped us understand broader trends across the organisation.

Data from the survey provided important insights. When asked whether they have a disability or long-term health condition, 7.3% identified as having physical disabilities and 4.6% identified as having learning difficulties or disabilities. Less than 1% chose not to respond to this question.

In a separate neurodiversity question, 14.7% identified as neurodivergent and 4.6% preferred not to say.

These results reflect patterns seen across the wider industry and reinforce the importance of establishing consistent, informed support structures across the practice – not simply for compliance, but to ensure that colleagues feel psychologically safe, seen and able to contribute at their best.

Practical adjustments that work

We are still at the early stages of this journey, and awareness must come first.

Building and embedding disability inclusion takes time and reinforcement. As the APM's Promoting Neurodiversity notes, targeted awareness training for managers and HR professionals is essential for improving communication, empathy and confidence.

Line manager training and wider staff education underpin every other adjustment. We can't make accommodations or recognise when they're needed without understanding what to look for.

Over the past year, we've delivered inclusion training to all staff, with further sessions planned. Neurodiversity now features regularly in internal communications, with gentle reminders woven through team briefings and leadership forums.

It's also important to note that many of the adjustments described in this article are practices I've been trialing in the Chichester office and the South Coast project management team.

We are continually assessing what works or doesn't work, and which approaches are ready to scale more widely across the practice.

These examples reflect both what we are doing now in certain teams, and what we are working towards embedding more consistently across the firm as awareness and confidence grow.

We are steadily putting practical adjustments in place; each one is a step towards making inclusion something people feel every day, rather than just paying lip service to it.

Clearer communication has been one of the most immediately impactful areas, which includes:

- sharing meeting agendas in advance, with clear objectives, to help colleagues prepare mentally and emotionally

- providing project-critical information both verbally and in follow-up bullet points to support those with working-memory challenges

- encouraging varied participation styles, such as cameras off or chat responses

- avoiding ambiguous phrasing like 'ASAP' or 'just'.

We have also made progress in enhancing workspaces and environments, offering quiet areas or noise-reducing headphones, avoiding harsh lighting and supporting hybrid working arrangements to allow for sensory recovery.

While flexible working requests and reasonable adjustments have been part of our employee rights and HR policy, our work through the EDI committee is focused on normalising these conversations.

As a result, staff feel safe and empowered to raise their needs proactively with line managers, rather than waiting until challenges become unmanageable.

In terms of workflow and management, customising task structures to align with people's strengths has proved to be one of the simplest and most effective performance enhancers.

Breaking tasks into smaller and more manageable steps, explicitly identifying priorities – 'critical by Friday' versus 'nice to have' – and providing predictable routines all help reduce cognitive overload.

We have actively normalised the use of assistive tools such as speech-to-text software and in-meeting notes. I use these tools myself every day.

A strength-based approach also underpins how we allocate work. Assigning tasks based on individual strengths rather than hierarchy unlocks both performance and engagement.

In my own team, giving ownership of data analysis to a colleague with exceptional pattern-recognition skills not only improved risk reporting, but also boosted their confidence and motivation.

Building roles around strengths rather than rigid job titles benefits everyone and is one of the most reliable ways to translate inclusion into measurable results.

Alongside these practical adjustments, we are working to build supportive cultural structures. When senior professionals disclose their own neurodivergence, it often empowers others to be open too.

We are actively trying to normalise these conversations and create psychologically safe disclosure pathways.

Peer-mentoring networks are another area being explored by the EDI committee as a future initiative.

Finally, inclusive recruitment remains a crucial part of the picture. Transparency is key: sharing interview questions in advance, offering additional thinking time, and accommodating written or visual responses all help candidates perform at their best.

'Line manager training and wider staff education underpin every other adjustment'

Lessons learned and ongoing challenges

This remains a learning journey, and a few themes have become clear.

- Education is critical, and support can vary depending on a line manager's awareness, confidence and willingness to adapt.

- Many neurodivergent colleagues self-manage, building their own systems and coping strategies, but these can only go so far without formal support.

- Policies must be visible and accessible, and adjustments should not rely on trial and error or private negotiation.

- Consistency matters. No one should receive a reduced level of support simply because of who happens to manage them.

Psychological safety sits at the heart of everything. When colleagues feel able to be honest about cognitive overload, sensory stress or communication preferences, projects run more smoothly.

Leadership modelling is equally essential. When senior figures normalise adjustments, express curiosity rather than judgement and show vulnerability themselves, it accelerates inclusion across the organisation.

Small behaviours such as language choices, meeting etiquette and openness about personal needs set the tone for everyone else.

The progress we've made so far has already shifted conversations across our practice and shown how small, thoughtful adjustments can unlock extraordinary potential. We still have more work to do, but the direction is clear and the benefits are tangible.

Neurodiversity matters to our profession because it improves:

- retention – people stay where they feel seen

- innovation – cognitive diversity drives creative problem-solving and

- fairness – we design spaces for society; we must reflect it.

I encourage firms and leaders to start the conversation. Build a committee. Gather data. Train managers. And above all, listen.

By building workplaces where neurodivergent colleagues can thrive, we will not only improve project outcomes, but also build a profession that reflects the world we serve.

'Leadership modelling is equally essential. When senior figures normalise adjustments, express curiosity rather than judgement and show vulnerability themselves, it accelerates inclusion across the organisation'

RICS comment

Inclusive space and design go beyond aesthetics and functionality; they focus on creating environments that accommodate the diverse needs, experiences and abilities of all individuals.

By intentionally considering inclusivity in the design process, we can cultivate spaces that promote accessibility, foster a sense of belonging and empower everyone to fully participate and thrive.

Learn more through the RICS Rules of Conduct guidance: Inclusive spaces.

Abigail Blumzon FRICS is a specialist in fire safety and facade remediation at Bailey Partnership

Contact Abigail: Email

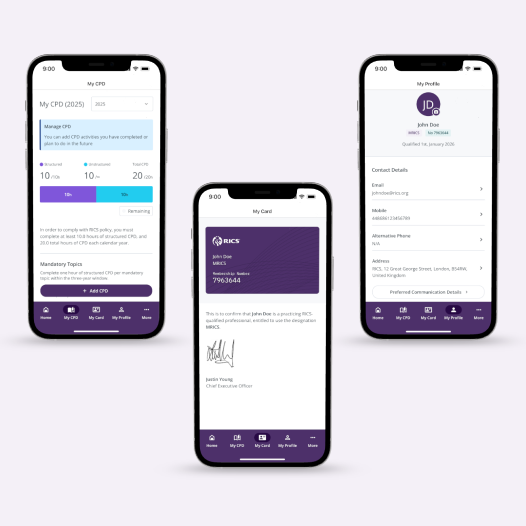

Discover the new RICS Member App: CPD on the go

RICS has introduced a refreshed CPD approach that prioritises meaningful, high-quality learning that genuinely benefits your work and is tailored to your specialism, career stage, and the real-world challenges you face.

The new app makes logging CPD simpler and more intuitive, so you can focus on the development that matters to your practice.