Chalara ash dieback, commonly referred to as ash dieback, is a serious disease killing trees across the UK. It was first officially reported Europe in 2012, although it is thought to have been in the UK from around 2004.

In an article a couple of years ago (Land Journal June/July 2018 pp.6–8), I outlined the emerging planning and budget allocation being implemented in some of the areas worst affected by ash dieback. In particular, I highlighted work being carried out in Devon, where the local authority anticipated net expenditure in the region of £26m to deal with the issue.

Since then the Tree Council has developed a toolkit for managing ash dieback, and has worked to raise awareness across the country with a series of workshops, principally aimed at local authority tree officers and financial officers.

The Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs' Ash Dieback Health and Safety Task Group meanwhile continues to work with key parties to develop clear guidance. Recent documents from the Forestry Commission and other bodies are also helping to develop our understanding of this disease and how landowners and managers need to respond.

Ash dieback primarily affects the common ash tree Fraxinus excelsior, and is caused by the vascular wilt fungus Hymenoscyphus fraxineus, initially known as Chalara fraxinea. It is often compared with Dutch elm disease; both affect trees in a similar way, but the way they are spread is different, with Dutch elm disease carried by the elm bark beetle of the genus Scolytus and ash dieback spread through the air by fungal spores from the central leaf stalks on the previous year's fallen leaves.

No one is certain whether all ash trees will die, but experience from mainland Europe where the disease has been present since 1992 suggests that most will decline or die over the next ten to 15 years. Currently the fungus affects most of the UK as shown on the Forest Research Distribution map, which illustrates the spread of the fungus and those areas identified in 2012 that still have living ash trees.

There is anecdotal evidence that younger trees seem more susceptible, with older and larger trees lasting longer, but this does not mean they are resistant; it simply means the death of the tree takes longer with increased stem diameter.

Many trees that fall or shed limbs appear to have a secondary pathogen, such as shaggy bracket (Inonotus hispidus), honey fungus of the genus Armillaria, or giant ash bracket (Perenniaporia fraxinea). These are not new but are taking advantage of trees stressed by ash dieback, which are increasingly susceptible to additional pathogens and succumb more quickly.

"Ash trees are currently integral to green corridors used by a variety of wildlife"

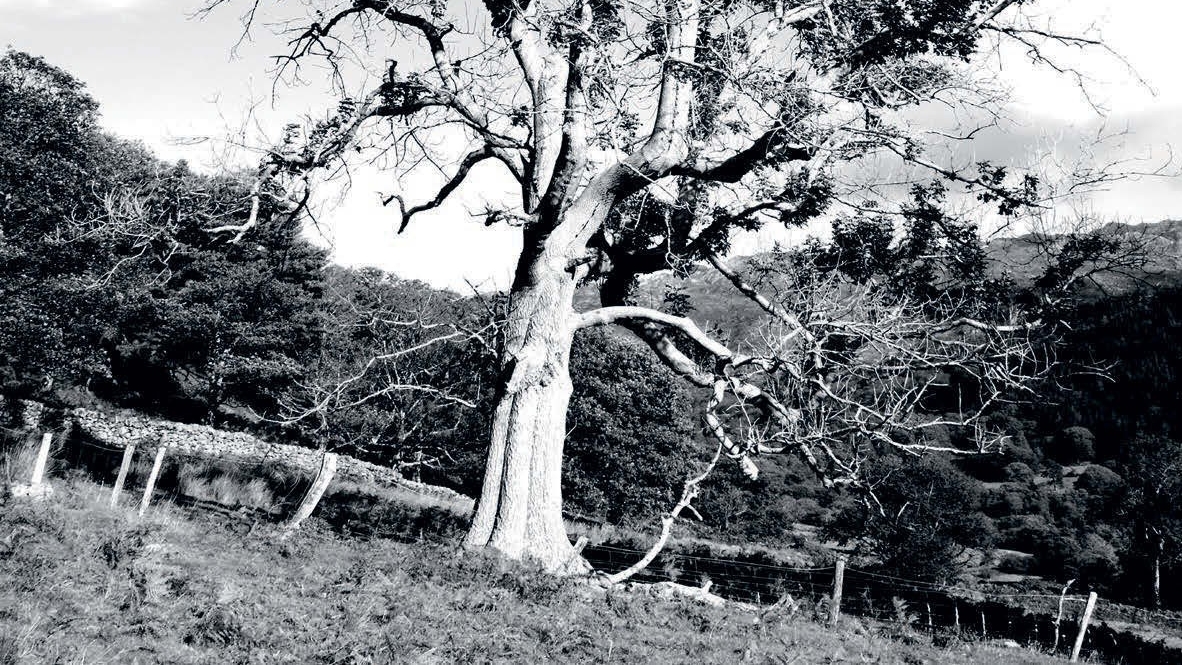

The ash is the third most common broadleaf tree in the UK. Its vigorous nature has contributed to its success, and undoubtedly some have established themselves in less-than-ideal locations, but they are a commonly recognised species and integral to the landscape.

As a staple forestry species, it is a valuable hardwood that grows well on a range of soil types, and its timber has a wide variety of uses. Ecologically, ash trees support 955 species of flora or fauna, of which 45 are exclusive to ash, and thus extremely vulnerable to the loss of their host. Ash trees are currently integral to green corridors used by a variety of wildlife.

Research by a team from the University of Oxford, Food and Environment Research Agency Science, the Sylva Foundation and the Woodland Trust published in May 2019 has calculated the true economic cost of ash dieback to the UK is estimated to be in the region of £15bn, with half of this over the next ten years, principally related to management and replacement costs.

Any person or organisation occupying land or property has a common duty of care under the Occupiers' Liability Act 1957 to take all reasonably practicable precautions to ensure the safety of trees on their land. Breaches of this duty could lead to a civil suit for damages. One of the critical issues for land managers therefore relates to let land or property. Tenancy agreements, in particular farm business tenancies, vary, so it is important to identify the duty holder and ensure that they are aware of their responsibilities in this regard.

"Ash trees support 955 species of flora or fauna, of which 45 are exclusive to ash, and thus vulnerable to the loss of their host"

There are also statutory duties under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 and related regulations to do all that is reasonably practicable to ensure that people are not exposed to risks. Understanding the impact of the disease on the structural stability of the trees and the safe working methods needed when dealing with them will be critical as the pressure on contractor resources increases.

Ash management framework

Anyone with responsibility for ash trees needs to understand the issue and tailor a practical and robust response to individual circumstances and client requirements.

- Resource assessment: collect the data, using technology as appropriate, to identify and understand the resource and its context, from roadside trees, urban trees and private gardens to large-scale commercial woodland. Drones and remote sensing are among the new technological approaches to data collection. It is likely that data will be collected in conjunction with any existing tree risk management strategies and associated survey works, following National Tree Safety Group guidance.

- Approach: develop a bespoke approach to reflect any critical objectives; for example, attitude to risk and the context and scale of the issue will be very different for large organisations such as Network Rail compared with a hill farmer in Yorkshire. It is likely that only a proactive approach will ultimately be defensible.

- Compliance: consider the relevant legislation and associated constraints, including – but not limited to – felling licence requirements, tree preservation orders, planning consent and conditions and European protected species designations.

- Execution: the arboricultural and forestry sectors are developing working protocols that will support the safe execution of any works on declining or dead ash trees. In most instances, the advice is that mechanised felling or elevated platforms will be required. Further guidance on safe working with dead ash trees is provided by the Forestry Industry Safety Accord.

- Replanting: it will be important to recognise the massive impact that ash loss has on the landscape and to replant as soon as possible, learning from the past and integrating diversity and resilience; suitable replacement species might include alder, aspen, rowan, hornbeam, lime, sycamore, walnut and wild service.

There are numerous useful guidance and information notes including the Forestry Commission's guidance operations note 46, the Tree Council's Ash Dieback Action Plan Toolkit and guidance for sites of special scientific interest from Natural England and the Forestry Commission. Most recently the commission has published operations note 46a for ash trees outside woodlands as well as the excellent Royal Forestry case study note all of which give a range of practical approaches.

On another positive note, scientists at the John Innes Centre in Norwich have discovered that the European ash has moderately good resistance to the emerald ash borer beetle that has devastated the tree in North America and which many were fearing would finish it off in the UK. While not immune, it is likely that healthy ash trees in the UK would not be severely damaged by this pest.

Additional threats

Sadly there are many other threats to Britain's non-woodland trees in addition to ash dieback. In particular the bacteria Xylella fastidiosa has caused significant loss of olive trees in Italy and is now moving across the continent and mutating to acclimatise to colder latitudes; it is known to kill a wide range of trees and shrubs, including some of the UK's key species.

The oak processionary moth has also been in the press, and while this does not affect the trees directly the public health implications can be severe; for instance, the hairs of oak processionary moth caterpillars cause severe allergic reaction in some people. Further details on all tree pests can be found on the UK Plant Health Risk Register.

John Lockhart FRICS is chair of Lockhart Garratt environmental planning and forestry consultancy john.lockhart@lgluk.com

Related competencies include: Management of the natural environment and landscape