The UK is currently undergoing two agricultural transitions: one in terms of funding and policy as the government assumes responsibility for the EU's former remit, and the other from analogue to digital technologies. As these transitions accelerate, with new payment schemes and natural capital markets emerging, digital mapping and geographical information systems (GIS) are playing an increasingly important role.

It is critical that we balance the growing – and at times, competing – demands for land use from agriculture, development, green energy and the need to preserve biodiversity. But it is here that GIS comes into its own.

Spatial data – which visually represents information on a map and allows it to be layered – enables land to be understood and assessed with much greater clarity. Accordingly, GIS and digital mapping are rapidly growing in popularity.

Certainly, as the value of combining geospatial data and insight with land management to maximise nature recovery and access natural capital payments becomes clearer, we at Land App have seen our number of users double since 2020 to 20,000.

Digital mapping offers clearer view of complexity

Assessing land use at the landscape scale offers a new and much-needed perspective. Research on nature corridors – in particular the 2010 Making space for nature review carried out by Prof. Sir John Lawton for the government – has demonstrated that day-to-day land-use planning must ensure habitat connectivity. Landscapes operate as an ecosystem, so protecting and creating nature corridors is critical to maintain biodiversity.

Thinking at this scale is complex, however, and it requires multiple stakeholders to plan and design a sustainable landscape coherently. It forces us to ask how we can align the competing priorities of the food system and the resilience of agricultural businesses – both of which often place the onus of decision-making on individuals – with the imperative for collaborative land management.

Whether the focus is on an individual farm or across an entire landscape, developing a clear and detailed understanding of the present state of nature is essential for establishing baselines and measuring progress. Traditional paper mapping makes this difficult, if not impossible, mostly due to the lack of dynamic information that can be derived from such maps.

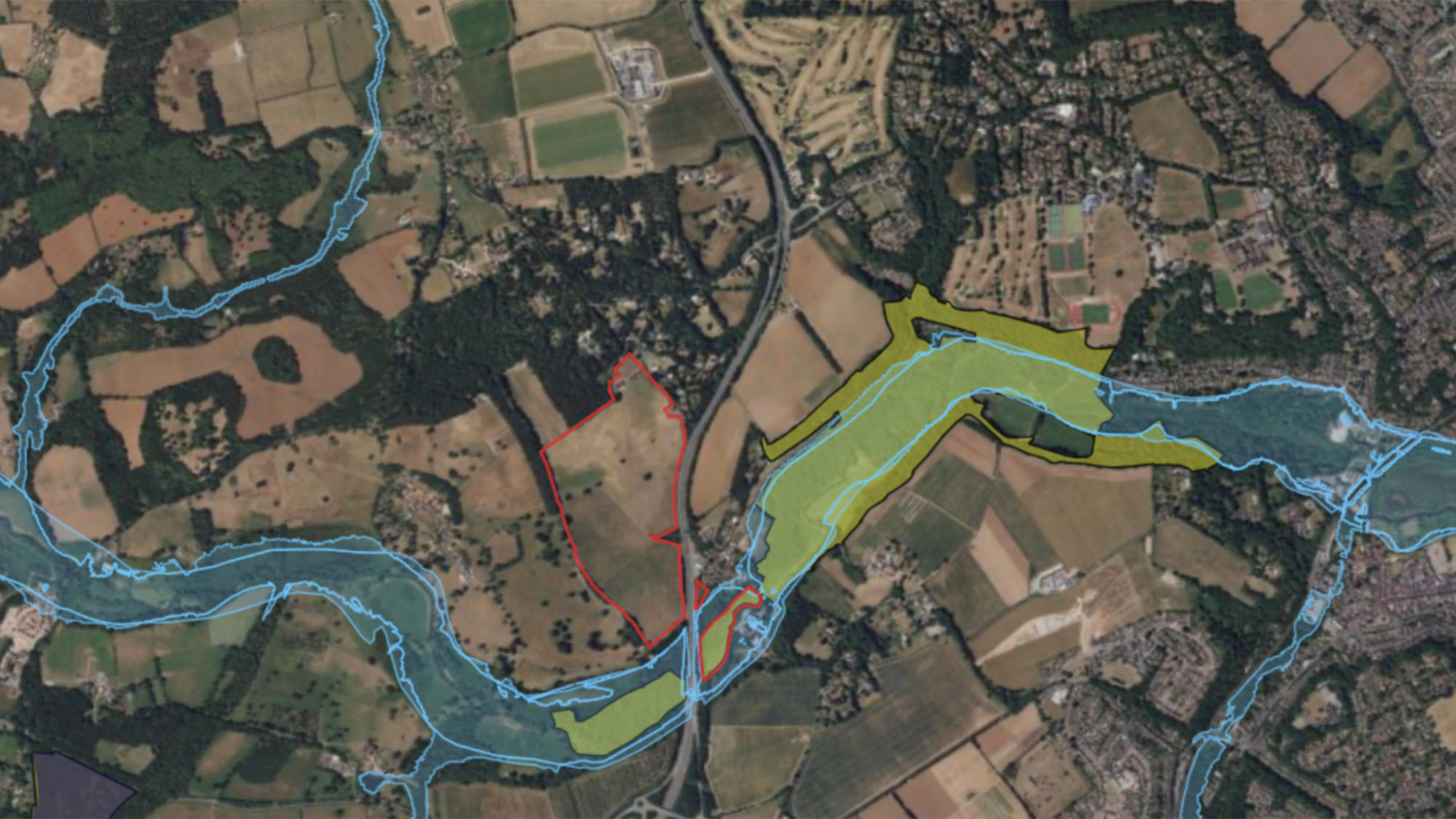

GIS, however, allows you to create layers so you can plot relevant information and data about your area of land on top of one another. Consequently, you can develop sophisticated and accurate plans that act essentially as a digital twin, contextualising the land with satellite imagery and datasets such as peatland, sites of special scientific interest or flood zones. Understanding current land use makes it easier to assess future opportunities.

Figure 1: Example map shows overlaying relevant data layers for peatland with additional option payments under the England Woodland Creation Offer. The EWCO checker tool will be released on Land App in November. © Land App

Data helps clarify funding potential

In the current time of unprecedented agricultural change, the insight provided by geospatial data and environmental science is invaluable to farmers, landowners and land agents. Traditional paper mapping simply cannot incorporate enough complexity to assess which scenarios will be viable.

Being able to gauge in minutes whether your land is eligible for Countryside Stewardship, biodiversity net gain (BNG) or the England Woodland Creation Offer (EWCO) – to name but a few schemes – helps simplify and streamline applications.

The Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Geospatial Commission are currently writing a land-use framework for England, a policy that acknowledges the need for the best land-use decisions for the future.

Indeed, in its Finding common ground report, the commission points out: 'To get the best value from land[,] we need to have good-quality data and information that describes its current use and the ability to apply analysis to determine potential future uses and their impacts.'

Essentially this depends on the idea of resilience, both ecological and financial. If data and science can be made accessible and linked to a means of designing funding applications, then the path for landowners to receive adequate funding to improve their land becomes much clearer.

Moreover, as digital mapping allows for measures to be co-designed as part of the landscape, farming cluster facilitators can align individual plans so they have an impact that goes beyond individual tracts of land.

By adding environmental science datasets such as the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology's e-planner or the Forestry Commission's EWCO data layers to mapping software for agri-environment schemes, landowners can make robust and environmentally positive decisions for their land.

But funding is crucial: if we place a higher value on good decisions, it creates a financial imperative that corresponds to targeted interventions promoting nature recovery.

'By adding environmental science datasets to mapping software for agri-environment schemes, landowners can make robust and environmentally positive decisions for their land'

Figure 2: Red line ownership boundary of Norney Farm, Surrey, overlayed with two geospatial data sets highlights where the farm intersects with important geographic or ecological features, such as flood zones. © Land App

Natural capital markets require measuring and monitoring

Where payments are made to create, retain or improve ecosystem services, we need a reliable system for planning, recording and monitoring this emerging market and its effects. The idea of a digital twin makes this considerably easier, especially given the capacity for data to be analysed to explore where natural capital and biodiversity could be improved or created.

As these markets focus principally on land-use change and the value this creates – a concept known as additionality – it is essential that such uplift is calculated using accurate and reliable data.

Metrics for calculating biodiversity credits, such as Natural England's Biodiversity Metric 4.0, enable market prices to be calculated against a standardised system. Habitat baselining, which can be done digitally, goes some way to allowing this: layering a future scenario map over a baseline allows you to calculate a potential uplift in biodiversity, and therefore adjust and optimise future land-use strategies before they are implemented.

Although the markets and technology to underpin them are both still maturing, progress has already been made. Not only can land managers and advisers access crucial land-use information dynamically, but they can then act on this data to design a funded – and, crucially, ecologically resilient – future for the land.

Collaborative schemes such as Landscape Recovery mean we focus on connectivity and ecosystems as whole as much as individual improvements. Digital mapping and the precision this brings represent a significant move towards achieving holistic and coherent planning for ecosystem recovery.

Undoubtedly, the agricultural transition to more sustainable land use is complex, requiring not only substantial investment but ensuring natural capital payments sufficiently value improvements and lead to meaningful change.

What remains clear, however, is that land management is benefitting substantially from advances in land-use mapping and GIS tools, and there is still much to be gained from them.