For too long the Irish property and construction sector and the housing market in particular have been characterised by boom and bust cycles. The Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland (SCSI) is determined to play its part in building a more sustainable model.

But it won't be easy. Ireland's housing market continues to be affected by an affordability and viability gap, meaning that only half the houses required to meet demand are being built at present. This is why, although most people in Ireland aspire to own their own home, a third of those in their 40s are renting, and the country has one of the highest rates in the EU of young adults living with their parents.

The SCSI's recent national conference was fittingly entitled A Chance for Change, and we hope that the Irish government will see that the pandemic has presented an opportunity to make a new start.

Supply and demand

We say this because, while there are a lot of unknowns in the market at the moment, something we do know is that the rate of construction inflation is decreasing.

We know this because the SCSI tracks the movement of tender prices being charged by building contractors for commercial building in our tender price index. Our report for the first half of 2020 crystallised for the first time the impact on tender prices from the reduced workload due to COVID-19.

The index highlighted that tender price inflation had decreased to 0.9% for the first half of 2020 from 2.8% for the corresponding period in 2019. Members active in this market are advising that this trend is continuing; we will issue our report on the second half of 2020 soon.

The construction industry in Ireland built up a significant capacity to meet market demand for construction services before COVID-19 and, with shrinking demand for its services in certain sectors such as hospitality and retail, it is our view that construction tender prices will not rise significantly this year, primarily because of increased competition for a shrinking market. We would note that the trends in the commercial tendering market also reflect those in housing construction.

So there's the opportunity: a shortage of houses and apartments and construction inflation slowing. That is why we believe the government should embark on a large-scale public-sector housebuilding programme through local authorities.

Local authorities will need the help of the private sector, however. This could involve the private sector developing on public lands, or building turn-key projects for approved housing bodies or local authorities.

Statistics reveal extent of shortfall

Figures from the Banking and Payments Federation Ireland indicate that house completions will be down to around 19,000–20,000 in 2020. Based on current output predictions, the SCSI believes it will be 2031 before new housing and projected demand reach equilibrium.

It's simply unacceptable that Ireland, in 2021, has failed to ensure an adequate supply of suitable and affordable properties is available for young people who wish to buy their own homes.

As one of the key speakers at our conference, Dr Rory Hearne from Maynooth University, pointed out: "Housing is at a crossroads in Ireland. We can continue lurching from crisis to crisis, with Generation Rent, the homeless, and future generations locked out of affordable homes; or we can tackle the roots of the problem." Costs are one of those roots.

Comparing public and private build costs

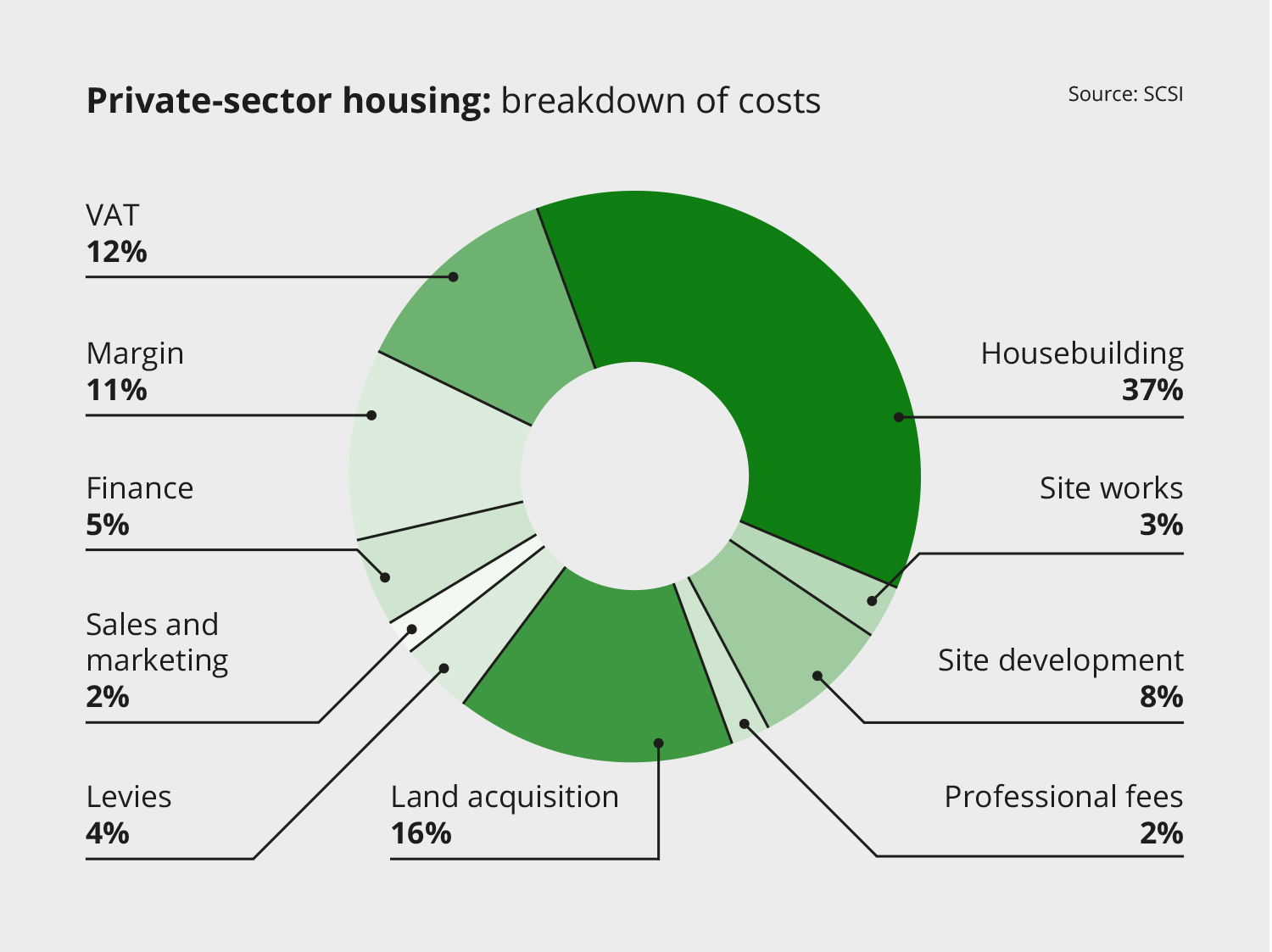

Clearly, property is expensive and time-consuming to produce. As outlined recently in our report The Real Cost of New Housing Delivery, the average cost for the private sector to build a new 3-bedroom semi-detached house in the Greater Dublin area is €371,000, as broken down in Figure 1.

Our independent analysis found that 48% of this comprises hard costs, including labour, bricks and mortar, while the remaining 52% derived from soft costs such as land, VAT, margin and levies.

Recently, Ireland's Department of Housing released figures on social housing procured by local authorities around the country. These attracted some attention on social media, with comparisons being drawn between the lower public-sector figures – around €277,000 in south Dublin and €243,000 in Waterford, for example – and the private-sector figure of €371,000 calculated by the SCSI. Although it's positive to see these issues being debated, like is not being compared with like in this instance. It is important to explain why.

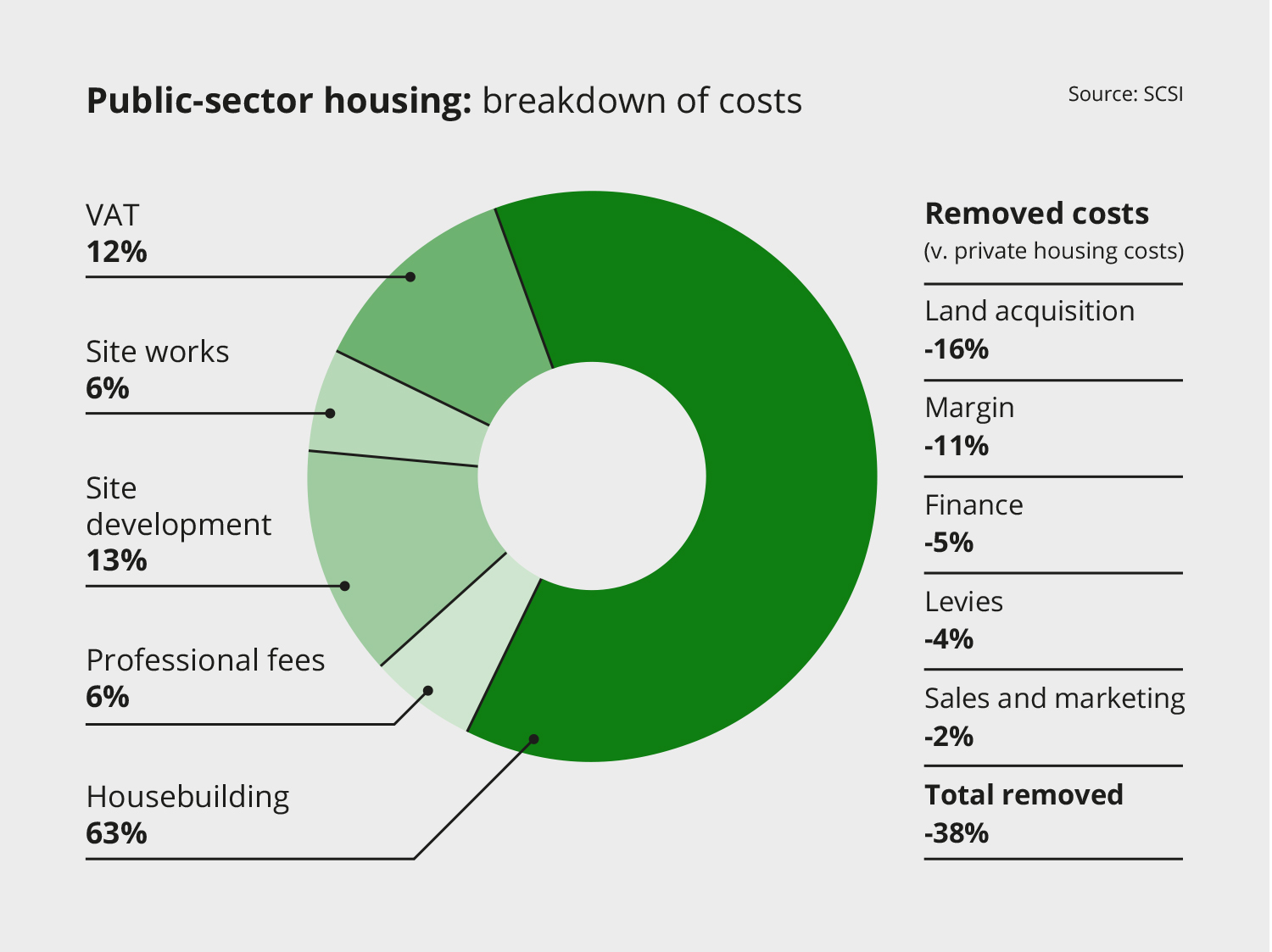

While our report focused on a privately built 3-bed semi – this is the way most new homes are built in Ireland – it also identified that public-sector housing is more cost-effective and can be produced for €210,000–230,000 per unit as broken down in Figure 2.

Why the substantial difference? Let's start with size. Public-sector housing is typically smaller than that in the private sector, and can be 20–25m2 less in terms of floor area. Obviously, the extra area of privately built housing comes at a cost and must be reflected in any comparison.

- land costs will be significantly lower than those for the private sector

- there is no developer margin

- finance costs will be minimal

- no local authority levies or contributions are required

- there are no sales, marketing or legal costs.

So while the hard construction costs are generally quite similar in the private and public sectors, if you remove the 5 soft costs listed you'll see there is a substantial difference – on average, €141,000 – between houses built privately and publicly.

We must, however, stress that this saving primarily arises where the Exchequer forgoes costs such as those of replacing land, while local authority levies for the provision of social housing are also waived.

Although the focus at present is about housing supply, it is our view that the costs forgone by the Exchequer in the provision of social housing should be accounted in a value-for-money assessment when comparing it to private-sector provision.

Push for public-private cooperation

Most commentators agree that to meet existing demand for new homes in Ireland, the annual requirement is about 35,000.

As noted in our report, there is a major affordability gap for first-time buyers trying to purchase a home, and this raises serious questions about the viability of new housebuilding in the private sector.

Based on these figures and the shortage of supply, we believe the government should ensure local authorities have the resources they need to start large-scale building programmes to supplement private-sector output.

The SCSI does not believe there is a single solution to this problem. The answer is a joined-up, public- and private-sector response to increase supply. That is why we are advocating a multifaceted approach, including the establishment of a commission on housing – as set out in the current administration's Programme for Government – to review all elements of housebuilding and associated costs. It is also proposing to create a national centre of excellence.

- tax treatment of new housing, particularly for first-time buyers

- the cost of the public procurement process

- best practice in considering any cost implications of new regulations

- how difficulties and costs associated with utilities can best be managed.

It is our view that new regulations and statutory measures should be subject to an independent cost–benefit analysis to assess their effects for the consumer.

There is no free pass for construction on this issue, and it behoves the industry to deal with the hard costs of building and increase productivity by adopting the latest technology. The SCSI is looking to advance this agenda as it chairs the Construction Industry Council Ireland and participates in the Construction Sector Group. It is also proposing to create a national centre of excellence.

On the government's part, there are areas such as levies, utilities, land and tax that we feel it can review and reform to help bridge the viability gap.

The SCSI believes the Help to Buy scheme should continue to assist first-time buyers with deposits, while consideration should also be given to introducing a shared ownership scheme similar to the UK model for those looking to get on the property ladder.

We also maintain that the government should leverage the Land Development Agency and local authorities to be more proactive and innovative in social housing supply by using private-sector developers to provide alternative models.

Significant procurement delays are a common feature in social housing programmes, and this is an area that needs reform and could benefit from input from the private sector.

Sustainable emphasis

Building sustainably is now more important than ever, and given that Ireland's population is projected to grow by 1m by 2040 and a further 1m by 2050, constructing at scale and more compactly in urban areas is a key requirement for the future.

As we have seen, work and lifestyles are changing dramatically in response to COVID-19, and the design and construction of new homes, particularly apartments, need to adapt accordingly.

But of course it is not just new homebuilding that requires attention. Revitalising and repurposing commercial property and retrofitting existing residential properties in rural towns and cities will also play a key role in supply.

We have repeatedly said there is no single solution to the housing crisis. It will take private and public sector input, expertise and collaboration.