The summer lockdown of 2020 in England allowed some of us who were working from home to explore parts of our neighbourhoods where we had not previously ventured. I took the opportunity to poke around bits of north London close to where I live.

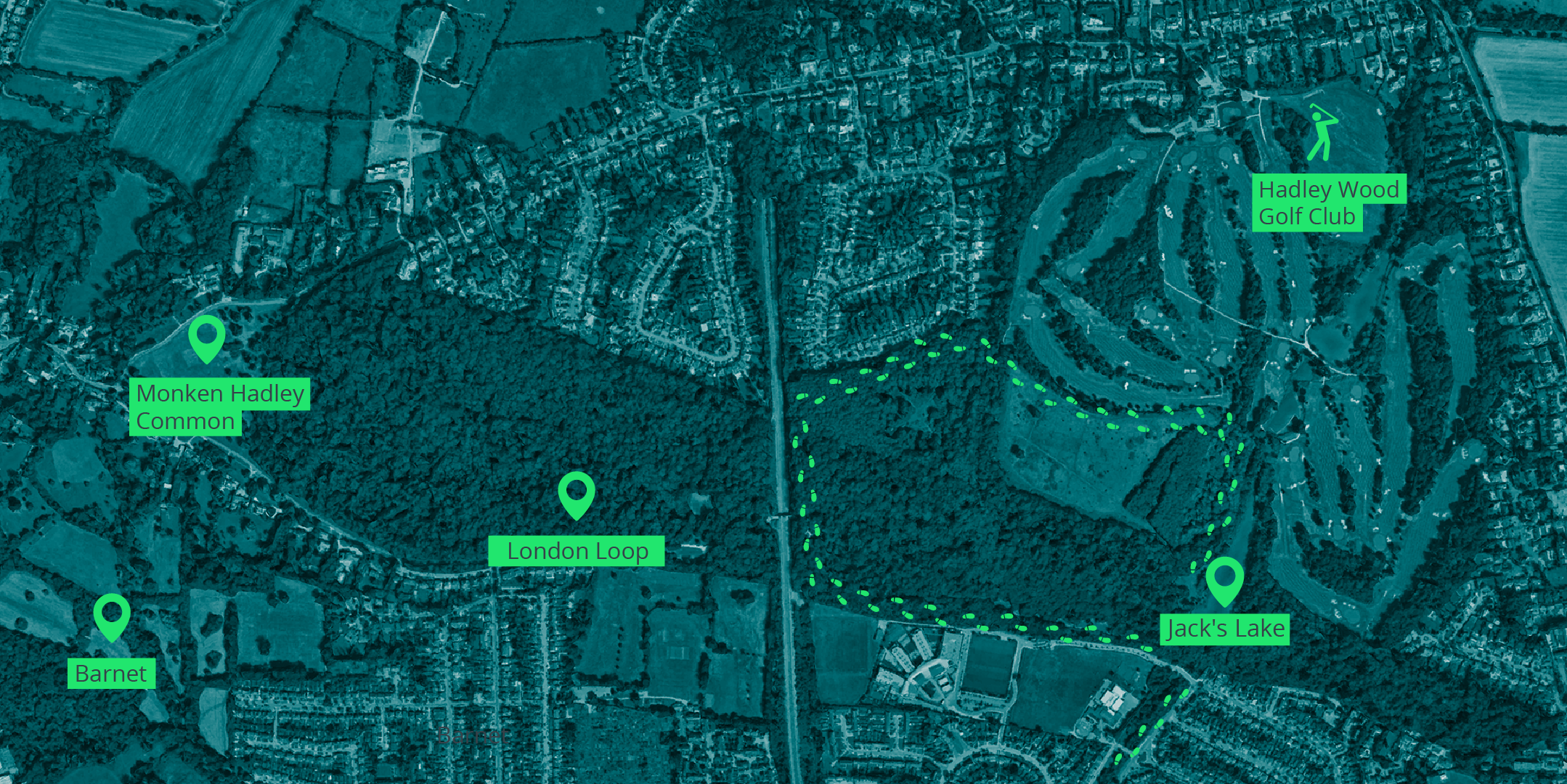

Most days my walks took me from familiar Victorian terraced streets into the green fringes of Barnet. Reaching the edge of the built-up area, my route took me along a path that plunged into the dense, ancient woodland of Monken Hadley Common.

This comprises part of the London Outer Orbital Path (LOOP) linking Cockfosters at the end of the Piccadilly Line to Chipping Barnet a few kilometres to the west. In the heart of the woodland lies Jack's Lake, a popular spot for fishing and picnicking.

On a map, the common's straight northern edge marks a clear boundary between the London Boroughs of Enfield and Barnet; a buffer of green belt separating the wealthy community of Hadley Wood – home to footballers, pop stars and bankers – and the working-class neighbourhood of New Barnet immediately to the south.

The dividing line is not just administrative or economic. Visitors to the common unfamiliar with the well-trodden paths through the trees find their route blocked by a battered sign nailed to a tree warning:

With club membership capped at 500 and fees of more than £2,000 per year, the course is an extraordinarily exclusive use of land. Yet is it far from unique. It is only one of seven courses in use in Enfield, and its proximity to the borough's boundary with Barnet places it ten minutes' drive from half a dozen more.

Enfield's courses together take up an astonishing 330ha, around 4% of the borough's total area. Two – Hadley Wood and Bush Hill Park – are privately owned, and yet the freeholds to the five other courses are under public control.

One, on the far eastern flank of the borough, is owned by the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority. The other four belong to Enfield Council, totalling 180ha. Coincidentally, this is almost precisely the same area of green belt that the borough is currently – and controversially – proposing to remove from its green belt in its draft local plan.

This is a common pattern across London – particularly in the outer boroughs where fingers of green belt push their way towards the centre between radial rail and tube lines. Nearby Barnet has nine courses; Bromley in the south east of London has 11. Although Richmond upon Thames has only seven courses, together they take up 7% of the borough's area, the largest proportion of any in London. Southwark's Dulwich & Sydenham Hill Golf Club is the closest to central London, owned by the Dulwich Estate, and extends to more than 33ha in the borough's southern tip.

At the time of writing there are 94 golf courses in use in Greater London. Cumulatively they occupy an area greater than the whole of Brent, which is home to 330,000 people. London's publicly owned courses alone – of which there are 43 – take up an area larger than the borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, with a total population of 185,000.

Courses represent inequitable land use

When the city is under such pressure to provide homes for a growing population and with house prices continuing to spiral upwards, it is only right to question whether golf represents a just use of a scarce resource.

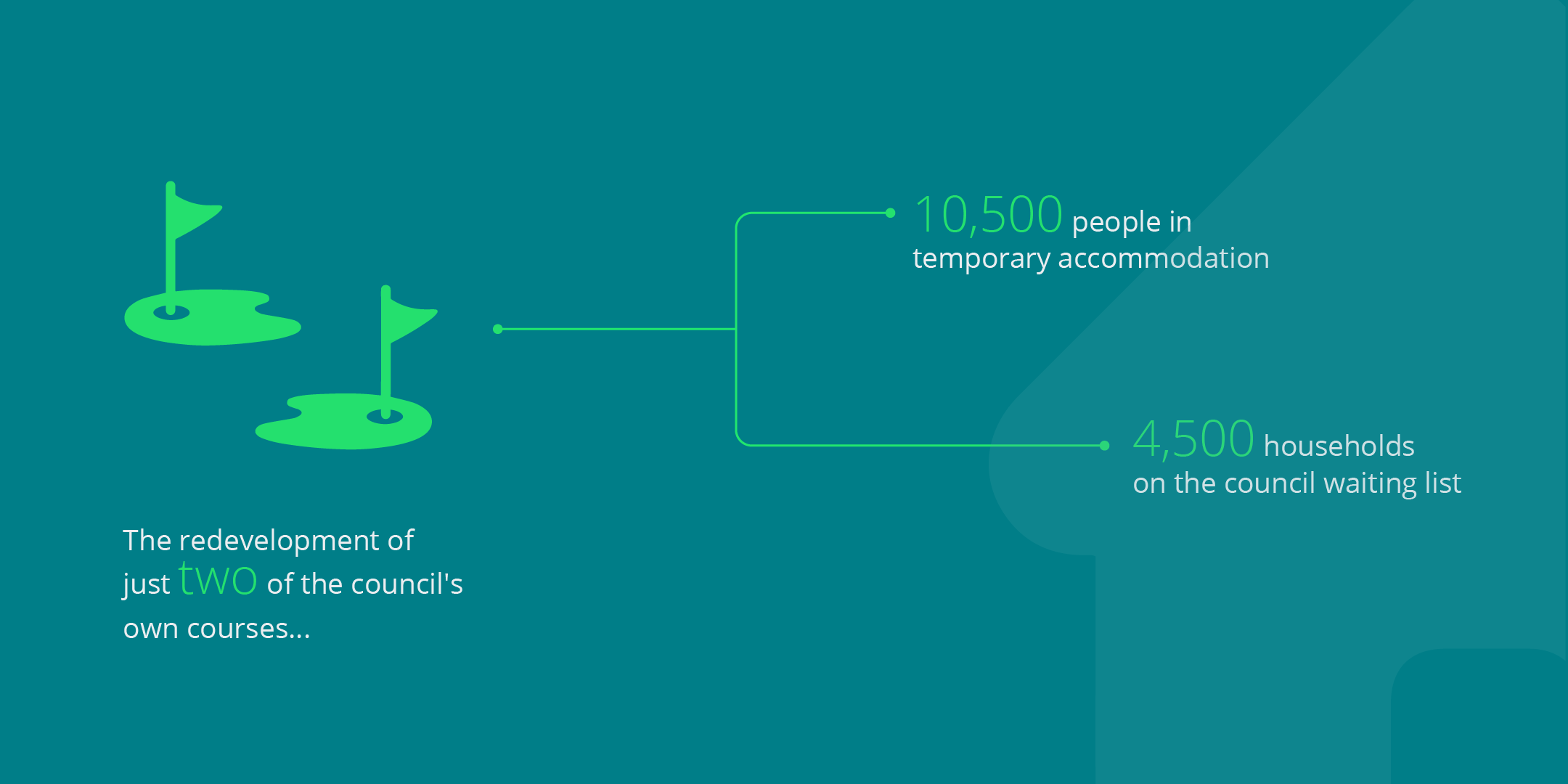

In Enfield, where there are six golf courses in the affluent western half of the borough, there are some 10,500 people living in temporary accommodation and 4,500 households on the council waiting list. Everyone in dire need of housing in Enfield could be provided within a home by developing just two of the council's own courses at modest densities.

Of course, wholesale redevelopment of Enfield's – or any borough's – fairways and putting greens is not realistic. Irrespective of the political challenges, the planning constraints are considerable. Most golf courses sit either in green belt or metropolitan open land, the latter being a planning designation unique to London that affords the same protections as green belt.

But surely it's right to question whether a game enjoyed by a small proportion of the population – around 1%, and likely far less in a relatively youthful city such as London, should occupy such a huge amount of valuable land.

It's true that golf has had a modest resurgence during the pandemic, but this is likely a temporary blip in a long-term decline. Despite this – and with clear evidence that many golf clubs are struggling to survive – the idea that we might take a more nuanced approach to the city's green spaces is usually met with outrage.

Others are investigating ways to release land for other uses that might provide much-needed income to invest in tired facilities, but they come up against the very planning barriers imposed to protect them from unwanted development. Even when development is necessary for a club's survival, the mere suggestion of building on surplus green space is met with opprobrium.

Rebuffing green space arguments

The argument reinforced by planning policy is that golf courses provide vital open space accessible to Londoners and they contribute to the city's ecology. But this is a fallacy. High water usage and frequent mowing of a largely monocultural landscape do not, as many claim, provide significant biodiversity benefits. While trees and hedges along the edges of fairways attract wildlife, the same argument could be made about motorways – and no one is promoting those as a means to green the city.

An average-sized suburban golf course might have around one-fifth of its area occupied by either fairways or green, half by rough, and 30% by tree cover. That's not an insignificant amount; but rewilding and opening these spaces to the public, as Lewisham Council did in 2019 at Beckenham Place Park, could offer significant ecological benefits to the wider area.

It's become clear during the pandemic, if evidence were needed, that open space has an important part to play in enhancing mental and physical well-being. Before the introduction of housing space standards there was nothing to stop developers building flats without external private amenity space, and millions of homes were built lacking such provision.

Fortunately, parks and gardens occupy around 11,500ha of land in London, and playing fields and sports grounds 5,600ha. That compares well with other global cities, and a third of London's area considered to be green.

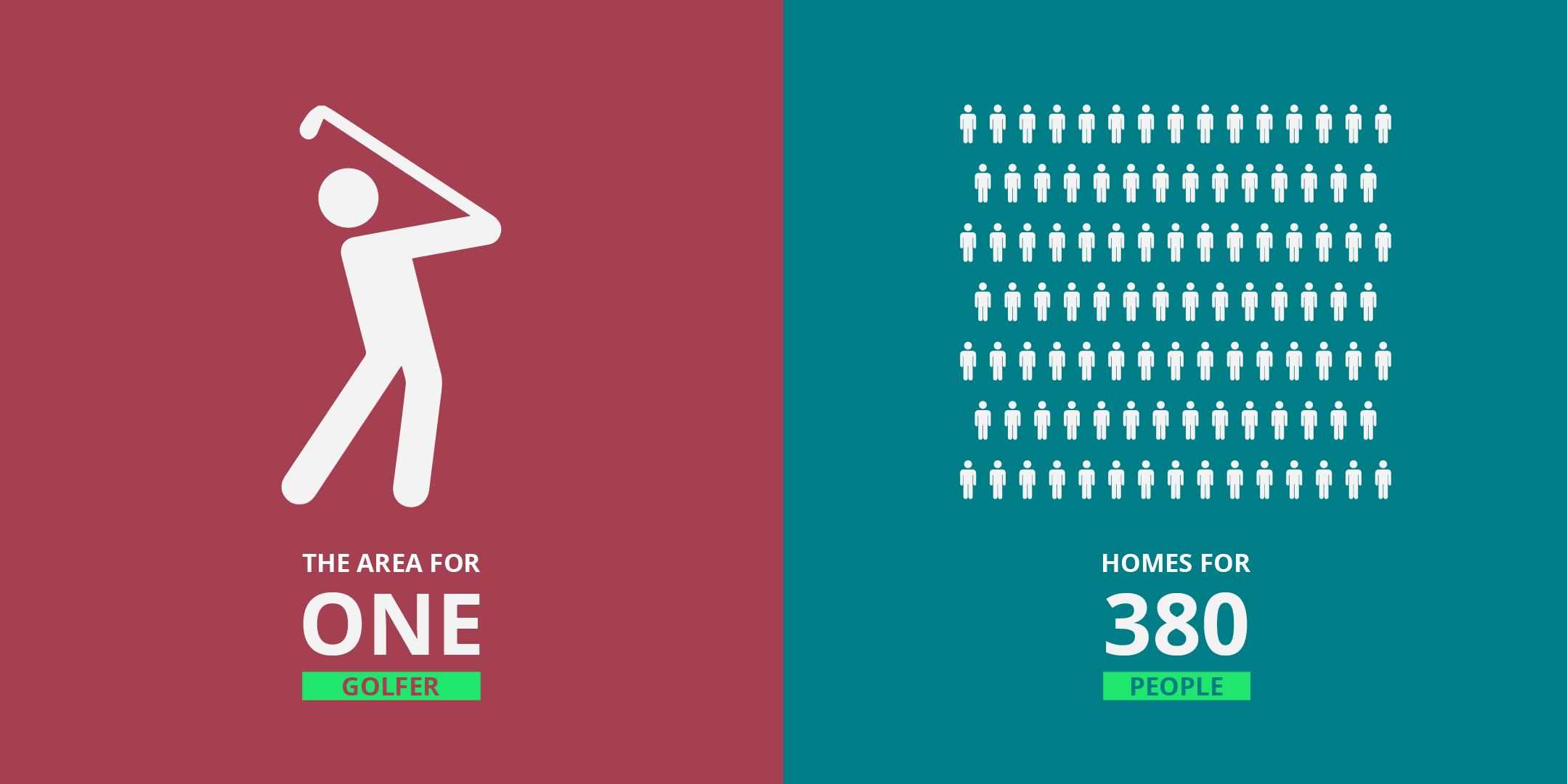

Golf courses are the third largest category of open space, though, occupying more than 4,330ha. With each golfer requiring around 1.6ha to play, this significantly limits the capacity of the city's courses to deal with a wider societal need.

Indeed, one of the definitions of metropolitan open land as set out in the London Plan is that it must 'serve either the whole or significant parts of London' – a difficult argument to make when the density of use is so limited and the barriers to entry so high. The area required for a single golfer to enjoy a round could provide homes for approximately 380 people. So is it time to start replacing golf courses with housing?

'The area required for a single golfer to enjoy a round could provide homes for around 380 people. So is it time to start replacing golf courses with housing?'

Although it is often presented as a binary choice between fields or concrete, development in open space does not have to be a zero-sum game. There is no reason why, with a little creativity and imagination, we cannot find ways to improve public access, promote biodiversity, provide vital new social infrastructure, parkland, food production, leisure uses and new housing, while at the same time respecting the important contribution that open spaces make to the character of suburban London – or even enhance them.

Releasing land for homes

Clusters of high-density housing, set in biodiverse landscapes and linked to the wider public transport network by cycle routes, would be entirely compatible with the broader policy aims of the London Plan, if carried out in an intelligent way. Policy must evolve to allow this to happen.

This could be achieved without a net loss of golfing capacity. The intelligent consolidation of a single course could shorten some higher-par holes without reducing their total number, releasing much-needed land for other uses and improving the experience for time-poor players.

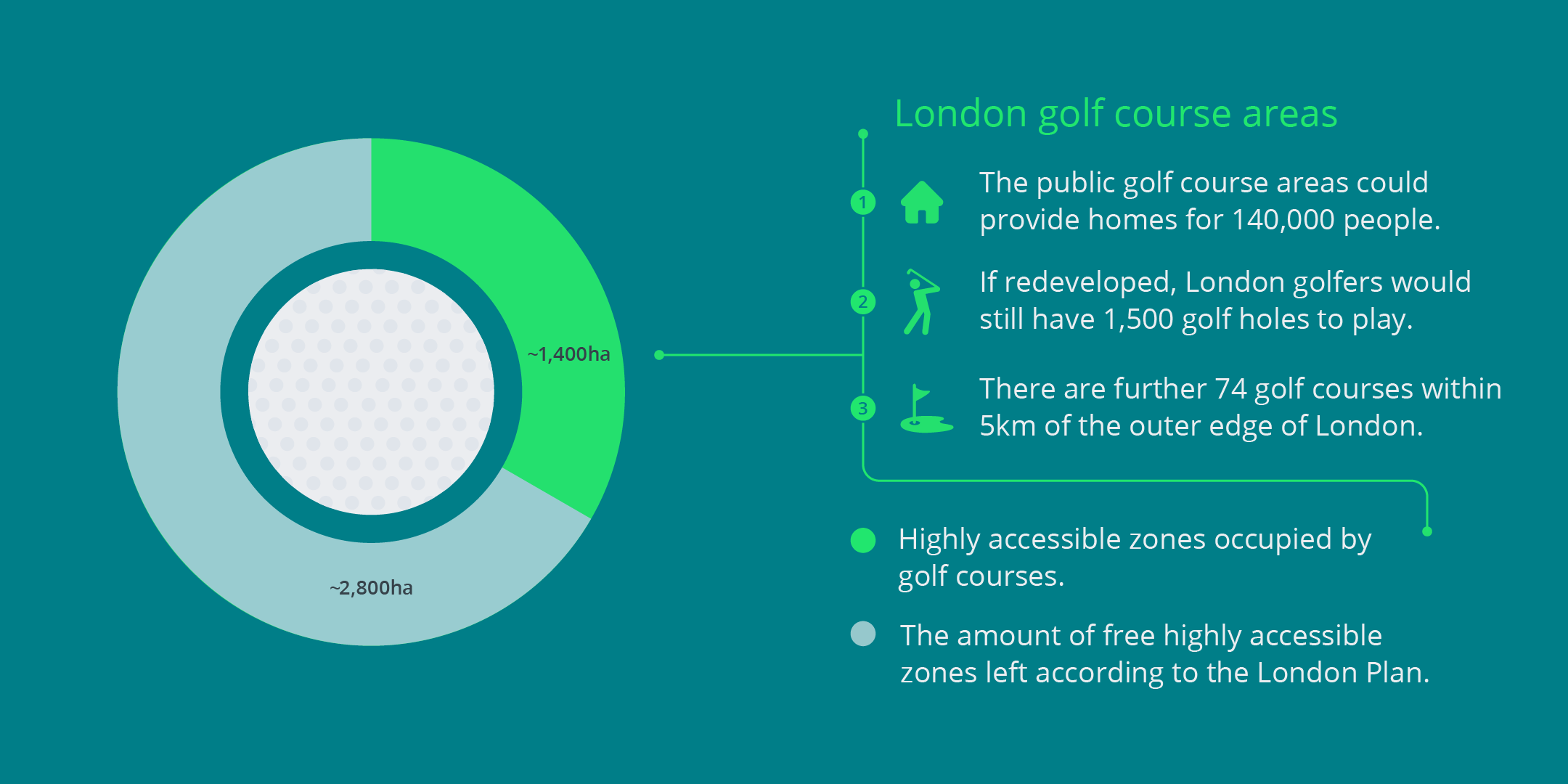

A surprising number of London's courses lie in easy reach of public transport or close to high streets. More than 1,400ha – exactly a third – lie within what the London Plan considers to be highly accessible zones and therefore suitable for incremental intensification.

The areas of public courses that meet these criteria could alone provide homes for 140,000 people, and London's golfers would still have 1,500 holes to play. Most of London's courses lie within the outer edges of the city, and there are a further 74 courses no more than 5km over the border into the Home Counties. Golfers are not deprived of choice when it comes to places to play.

The challenges facing London are myriad, and no single change will solve the current housing crisis. But failing to house those who need a decent place to live is not a result of factors outside our control, but a choice. Access to decent housing is one of the most significant contributors to social and economic inequality. Perhaps more sophisticated thinking about the use of land in London is one way in which we might start to bridge this divide.