Global crises in finance, food, environment and energy over the past decade have led to large-scale land acquisitions (LSLAs) in the global south – which have sparked debates about their socio-economic and environmental impacts.

- enhanced food security

- clean energy

- job creation

- rural infrastructure development

- broadened tax base

- eco-tourism.

- Their opponents are concerned about:

- land dispossession and involuntary displacement of local people

- environmental degradation

- local food security and sovereignty becoming compromised

- casualisation of jobs

- less access to water.

"They collaborate to promote economic growth and poverty reduction as public goods"

LSLAs are not new, but the current wave is specific in four main ways. First, LSLAs are happening in a highly connected global capitalist network, not within the national borders under individual states' control.

Second, development institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank Group, the Organisation for Economic Corporation and Development and the World Trade Organization are playing a big role in promoting LSLAs by arm-twisting host countries to liberalise economic policies and encourage investments.

Third, LSLAs give investors access to global market shares to the detriment of already financially constrained smallholders in host countries. Finally host country governments are enabling access to land as they liberalise investment policies, particularly agricultural policies.

The convergence of these four factors partly explains the two preferred modes of investing in land: low-risk direct land investments that purchase or rent land from landowners by an established operator; and indirectly, high-risk purchase and control of a stake in an agricultural company to increase its value. The latter investments can also involve land acquisition.

One way to invest in land is through a public–private partnership (PPP), where government agencies and private entities collaborate. Each partner contributes to setting goals, planning and decision-making and allocating resources, risk, benefits and accountability. They collaborate to promote economic growth and poverty reduction as public goods.

- the different incentive structures in public and private sectors

- prohibitive costs both direct and indirect

- the negative perceptions between the public and private sectors

- the high levels of competition and risk that are associated with valuable resources and assets.

PPPs as collaborative arrangements, responding to crises such as food, finance, environment and energy, raise ideological and operational concerns. While host governments need to boost the economy through investments in land, they lack capital and expertise. Although the private sector can offer this where it will increase profits, an LSLA PPP contract is likely to be challenging because investors perceive state agencies as slow, inefficient, and resistant to change. In LSLA deals, there is not only a willing seller and willing buyer, but many others, particularly multinational financial institutions, playing their role to encourage policy changes in host countries to enable private investments.

LSLAs in Zambia

The 1975 Lands (Conversion of Titles) Act prohibited the sale of land in Zambia. However, the Lands Act 1995 repealed the earlier legislation and allowed land tenure to be converted from customary land to leasehold. In 2002, the government decreed that nine farm blocks would be established in which 967,750ha of customary land would be converted to leasehold.

This farm block programme was modelled on contract farming. Each farm block was parcelled into the core venture – the largest parcel of the farm block for an agri-business – as well as commercial farms, medium farms and smallholder farms. Nansanga in central Zambia is one such block where smallholder, medium-sized and commercial farms were meant to produce crops to sell to an agri-business occupying the core venture. The agri-business would then export these in the sub-region and overseas.

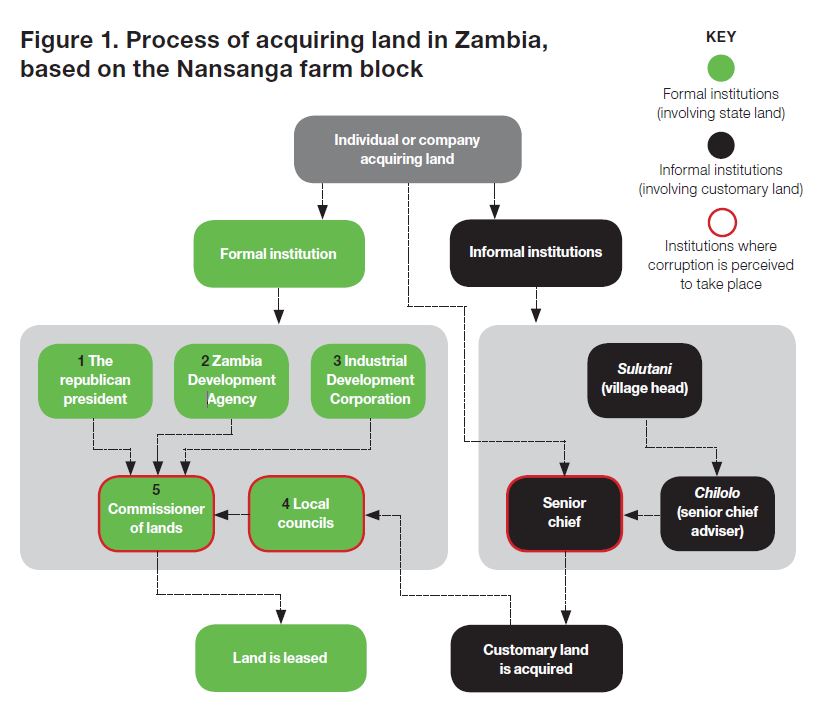

Figure 1 note: Local people in Muchinda chiefdom, the Lala, inherit land from their parents or are allocated land by the senior chief who, on payment of a $35 fee, issues a farm book. The book indicates the right to use land, but also that the land belongs to the chiefdom. Non-Lalas approach a sulutani who consults a chilolo. Land is sought, and if found in the chiefdom, a recommendation is made to the senior chief. If approved, the chief issues a farm book on payment of the fee. To lease land with a title deed, an application is made to the commissioner of lands through a recommendation from the local council. Land for development may need approval from the Zambia Environmental Management Agency and the Department of Resettlement, Office of the Vice-President

After converting customary land to leasehold, building roads and three dams, and issuing title deeds to would-be users of commercial and medium-sized farms, Nansanga has not gone into operation. Developed infrastructure has crumbled, and the core venture has not been occupied by any agri-business. This is largely attributed to the death of president Mwanawasa in 2008 and the change of government in 2011, which did not have the same agricultural policy as the previous administration.

Developed infrastructure has crumbled and the core venture has not been occupied by any agri-business. This is largely attributed to the death of president Mwanawasa in 2008 and the change of government in 2011 which did not have the same agricultural policy as the previous administration.

Before investing in Zambia, it's important to understand resources and the land tenure system. Since 1991, when the presidency of Kenneth David Kaunda ended, Zambia has been promoting pro-foreign investor policies and conditions, including the abolition of price controls, liberalisation of interest rates, abolition of exchange rate controls, 100 per cent repatriation of profits to investing nations, free investment in virtually all sectors of the economy, privatisation of state-owned enterprises, and trade reforms aimed at simplifying tariff structures.

" ... investors perceive state agencies as slow, inefficient, and resistant to change"

The land tenure system comprises two main components: customary land under traditional authorities, and state land managed by the commissioner of lands, on behalf of the president. These arrangements co-exist with different management structures. There are seven generally acceptable pathways of acquiring land in Zambia: five through formal institutions and two through traditional authorities.

The practice is that the socio-economic and financial status of the individual or organisation influences the pathway to acquire land. Multinational companies are more likely to go through the president, while foreign investors are more likely to go through the Zambia Development Agency.

The latter gives investors institutional support, including certificates of registration giving them access to land. To partner in public investments, the investor goes through the Industrial Development Corporation, a quasi-governmental body that promotes public–private investments. Urban individuals wishing to invest in rural areas are more likely to deal with the commissioner of lands, or approach the chief or local district council directly.

- macro level: the president, through the commissioner of lands

- meso level: district councils contracted by the commissioner of lands to carry out land governance functions

- micro level: traditional authorities, dealing exclusively with customary land.

- The interplay between land governance and the outcomes of LSLA deals is marred by party politics, underfunding, understaffing, lack of inter-ministerial coordination and what is locally called cadreism, a form of cronyism characterised by unlawful behaviour by political party sympathisers involved in illegal allocation of land that is nonetheless tolerated. Zambia does not have adequate institutional capacity to manage and govern LSLAs. Consequently, the negative environmental and socio-economic impacts of LSLA deals are more likely to outweigh the positives even if the latter are oversold and the former downplayed.

- The co-existence of formal and informal land tenure systems is a marriage of convenience between the state and traditional authorities. The many ways for acquiring land enable corruption in deals, while the state and traditional authorities have irreconcilable differences of interest in land governance – stalling the formulation of an enforceable national land policy.

- A chronic lack of data plagues Zambia's general land governance structure: not knowing how much land is state-owned and how much is customary land; the monetary value of rural, peri-urban and urban land; the types of investment in land; and the value of investments in land at national level. Because this information is lacking, land markets are not structured and the willing seller, willing buyer model dominates transactions.

Dr Andrew Chilombo is a consultant at the UN Environment Programme, West Africa sub-regional office in Abidjan, Ivory Coast chilombos@yahoo.co.uk

Related competencies include: Cadastre and land administration, Economic development, Legal/regulatory compliance