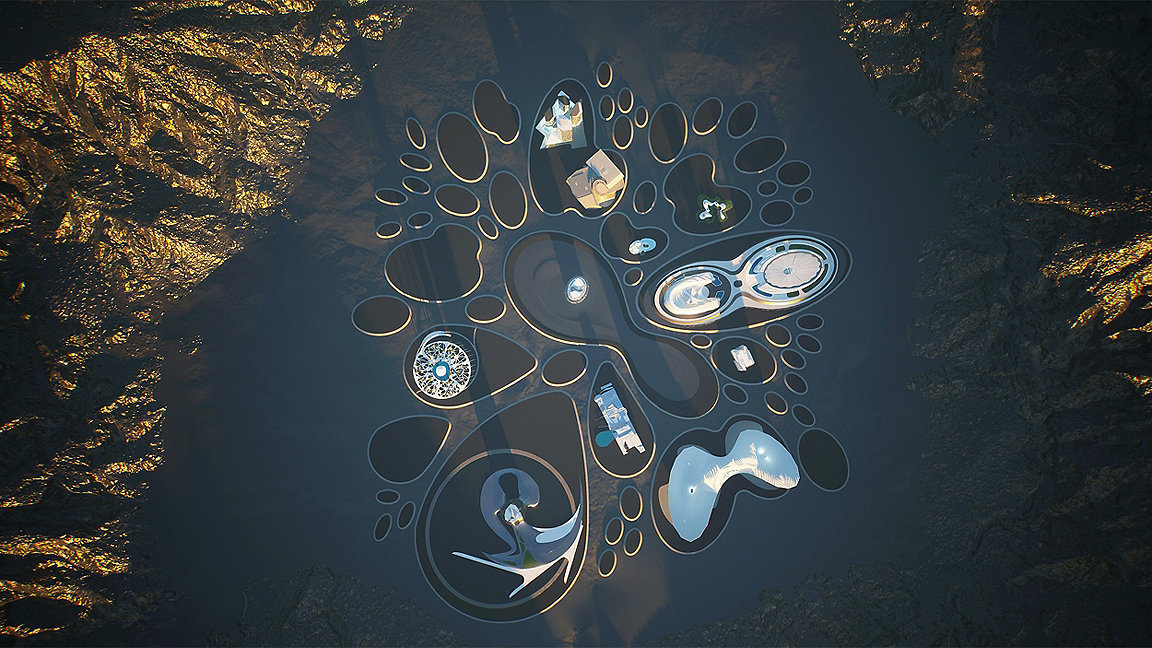

Metrotopia aspires to become a virtual communication hub in the metaverse. Image © Zaha Hadid Architects

The metaverse enables people to experience a different environment to their physical location, connecting and exploring computer-generated, primarily virtual reality (VR) worlds in real time.

For example, an employee working from home but in an immersive, virtual experience can feel as though they are in a meeting room with colleagues.

The terminology could confuse matters, however. There is not a single metaverse platform or technology; instead, it encompasses a vast interconnected network of virtual worlds, games, social media, and other digital experiences. Various tech giants have invested heavily in VR and augmented reality (AR) technologies to create immersive and engaging experiences that anyone anywhere can access.

While the metaverse is still in its formative stages, it could revolutionise the way we interact with each other and the world around us.

Metaverse develops land economy

The concept of land has taken on a whole new meaning in the metaverse. In these virtual ecosystems, land refers to plots of digital space that users can buy, sell and develop. Like that the physical world, virtual land can vary in size, location and value, with prime locations commanding premium prices.

As the metaverse grows and becomes more integrated with our daily lives, the concept of virtual landownership is expected to become an increasingly important aspect of the digital economy. Already, companies are emerging to support the buying and selling of virtual land, and virtual architects and developers are creating stunning virtual real estate for users to explore and inhabit.

What might this mean for surveyors? Transactions in the metaverse typically use non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that represent ownership of specific parcels of virtual land. NFTs themselves are unique digital assets, created and verified on a blockchain network. Each has a unique digital signature that proves its authenticity and ownership, making it impossible to counterfeit or duplicate.

On metaverse platforms, users can buy virtual land parcels with cryptocurrency and receive an NFT representing their ownership of the land. This allows users to buy, sell and trade virtual land just as they would physical real estate.

Once a user owns such a parcel, they can build and create a wide range of experiences and assets on it, whether virtual buildings, games or art installations. This means the metaverse has the potential to develop a vibrant economy.

Virtual landownership is also important because it allows users to establish a digital identity and participate in virtual communities. They can display their land and creations to establish their presence and reputation in the virtual world. They can even become virtual landlords by leasing their property in the metaverse.

Our colleagues at Deloitte in the Netherlands recently identified that demand in the virtual world also has the potential to affect demand in the real world. Their report says the need for actual retail space will decrease if virtual shopping, where users can, for instance, virtually walk through shops as an avatar, feeling and smelling products, is preferred over physical stores. Given that interdependency, might there one day be a trade-off between virtual and real property prices in all sectors?

How virtual and real estate differ

As compulsory purchase advisers, we considered whether metaverse land is indeed the same as physical land, and are metaverse land rights the same as physical land rights? In which case, might it ever be necessary – or possible – to acquire land compulsorily in the metaverse?

In the physical world, compulsory purchase allows certain bodies to acquire privately owned land or property without the owner's consent, in specific circumstances. Its purpose is to enable certain projects – such as the construction of roads, railways and airports – or urban regeneration, where there is a compelling case in the public interest. Could such a need ever exist in the virtual world?

Clearly, the properties of land in the metaverse are very different to those of physical land. One main reason for compulsory acquisition of land is the limited supply on our planet; so there are some circumstances where demands on that supply mean that private rights need to be overridden in return for compensation.

However, unlike physical land, metaverse land is not bound by physical constraints and can be infinitely replicated and modified, allowing more creative and flexible use cases. Theoretically, there could be an infinite number of metaverse worlds with infinite amounts of developable land. This might suggest that there would never be a need to acquire virtual land on a compulsory basis – more could just be created.

That said, location factors could prompt a readjustment in virtual land interests; for example, in prime locations where the relationship with other metaverse occupiers is particularly important.

One virtual land buyer reportedly purchased a plot of land next to rapper Snoop Dogg's NFT house in 2021 for $450,000 (£340,500). More recently, sportswear brands have acquired plots of land in metaverse ecosystems to create a presence there, showing that – as in the real world – specific interests can be important and valuable based on their relationship with others.

Another consideration is the legislative framework applicable to compulsory acquisition, which in the physical world varies globally depending on jurisdiction. The legal powers relating to land, and the circumstances in which its sale can be forced, apply to all land in that territory.

The same principle does not apply to the metaverse, however, which is not a nation of citizens governed by a head of state but instead an offering of a decentralised private entity. This led us to wonder who would govern any compulsory acquisition if it took place? So far we have not come across any equivalent frameworks.

Governance arrangements not yet clear

In due course, there could be situations in which virtual assets or virtual land in the metaverse are subject to acquisition by governing authorities or other parties for a public purpose or legal reason. For example, if a user's virtual asset or virtual land is in violation of the rules or regulations governing the metaverse, the governing authority with appropriate oversight powers could seize or revoke that asset or land.

Additionally, if the metaverse were governed by a decentralised or blockchain-based system, the rules of the network could allow for the seizure or redistribution of assets under certain circumstances. However, without a single legal framework applying to the metaverse, this would likely require collaboration between countries to determine the appropriate form of governance for virtual land rights.

Perhaps one day there could be a metaverse framework with parallels to the recently agreed UN High Seas Treaty, which establishes a legal framework for the use of international deep-sea resources and regulates activities to ensure that they are carried out in a safe and environmentally sustainable manner. This and similar treaties involve the cooperation of multiple countries and the establishment of international organisations to administer and enforce the rules and regulations.

As the metaverse is still an emerging concept, its governance is not yet fully established; neither is the way its real-estate economy operates. The circumstances that might require compulsory acquisition in the metaverse are therefore not yet clear. However, subject to take-up and demand it is possible that metaverse rights might need to be redistributed in the future. We continue to watch with interest.

Liz Neate is a director of real assets advisory at Deloitte LLP

Jack O'Neill is a manager of real assets advisory at Deloitte LLP

Related competencies include: Compulsory purchase and compensation, Data management, Legal/regulatory compliance