Two farmers exchanging Kenyan currency Photographer: Simplice, Shutterstock

Academics sometimes refer to decentralisation as one of the most important reforms in political systems of the past 30 years, with a majority of states around the world devolving some degree of authority and responsibility to the local level. Yet for devolution to fulfil promises of increased accountability, responsiveness and improved local governance, there also needs to be a level of fiscal decentralisation. How are local governments to respond to their citizens' demands and provide services effectively if they have no budgetary authority?

One of the core aspects of fiscal decentralisation globally is building the capacity of local governments to raise their own finances, also referred to as own-source revenues (OSR). Compared with sometimes unpredictable and untimely intergovernmental transfers, OSR can provide local governments with reliable funding and autonomy in service provision. OSR also increases creditworthiness and thereby supports access to external finance.

Ultimately, greater reliance on OSR also tends to strengthen the accountability of local governments, and gives them an incentive to improve service provision and representation in exchange for tax contributions.

The challenges of OSR

While their merits are largely accepted, using OSR systems effectively and efficiently remains a challenge for many local governments, especially in developing countries. Low-income countries generate around $12 per capita per year from OSR in local governments, compared with $2,944 per capita per year in high-income countries. Local OSR systems can also distort the way that markets would otherwise function because they can be cumbersome, costly to administer, coercive and prone to capture, where local economic and political elites manipulate OSR systems such that they serve their interests at the expense of the wider population.

-

insufficient tax authority

-

lack of tax collection capacity

- concomitantly poor tax policy.

In outlining these policy recommendations, the literature also commonly emphasises the importance of political leadership for successful OSR reform. This is needed because effective OSR policies and institutions may not be in the interest of tax collectors, politicians or economic elites, who benefit in one form or another from tax loopholes, lack of enforcement or reduced business and property tax rates. The UN Human Settlements Programme, UN-Habitat, suggests that more research is needed to understand how to foster the political will and leadership for reforming OSR.

Optimising OSR in Kenya

UN-Habitat has successfully supported the development of property tax systems in fragile contexts such as Afghanistan and Somalia, as well as strengthening OSR systems more broadly in places such as Kiambu, Kenya. The programme is developing an optimisation tool called Rapid Own-Source Revenue Analysis (ROSRA), which will help local governments to prioritise interventions and provide the largest possible return for investment in reform.

To test the tool, UN-Habitat launched a pilot with the County Government of Kisumu in April 2019. Kisumu is one of Kenya's 47 most economically significant counties, in the far west of the country on the banks of Lake Victoria. It is home to 1.2m inhabitants and Kisumu city, the third largest in Kenya.

Kisumu's ecology and climate lend it to agriculture, while its lakeside location and international airport have the potential to make it a hotspot for trade and tourism. To fulfil this potential, however, Kisumu requires significant public and private investment.

It needs to provide basic services to the 40% of its urban population living in slums and increase access to water and electricity, which at present are available only to 58% and 46% of the population respectively. With only 15% of roads being surfaced, Kisumu also requires significant investment in infrastructure to decrease transportation costs for agricultural produce and attract private investment in the county's underused rural areas.

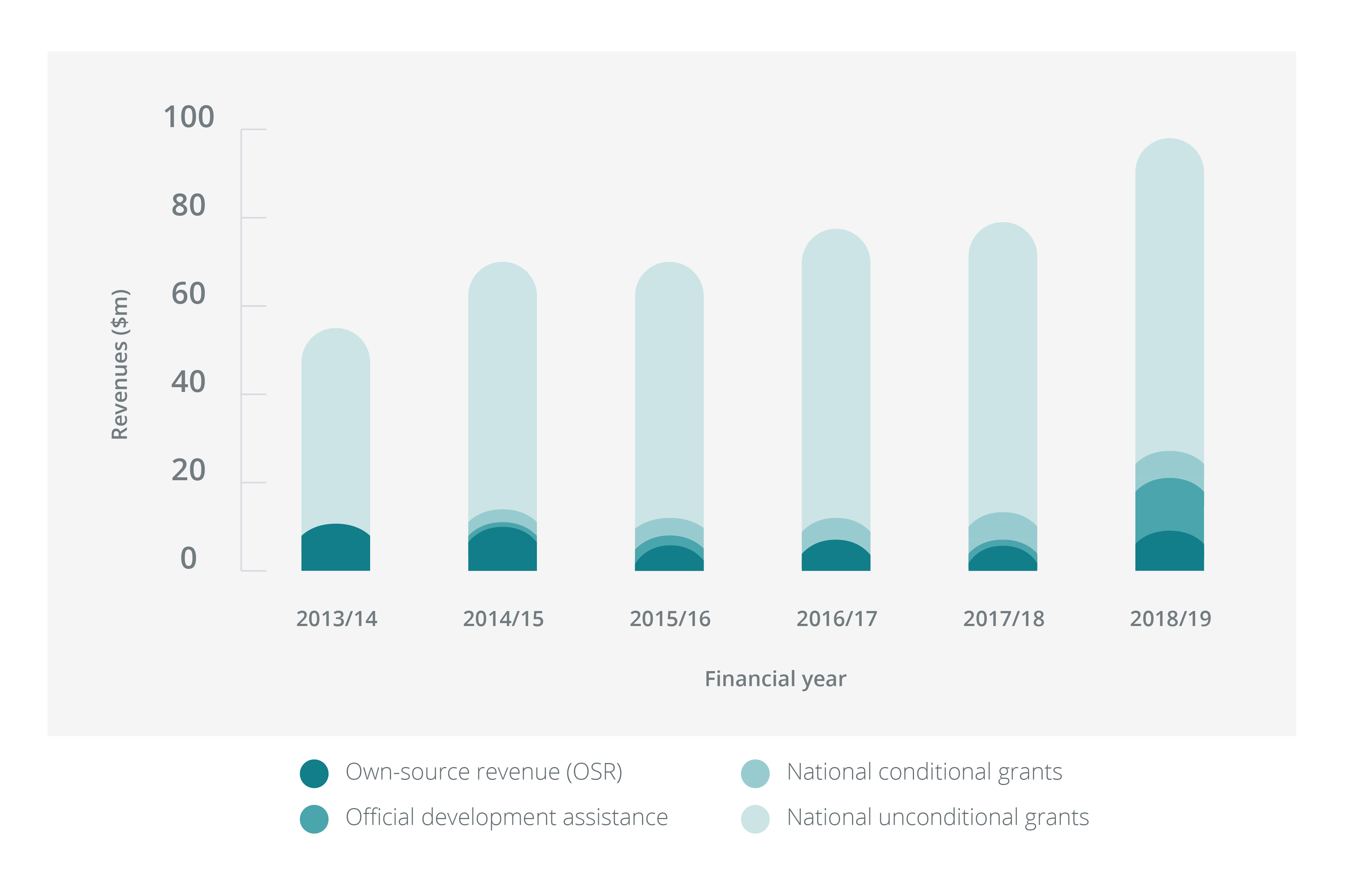

Investment on this scale requires significant reform and upgrading of its financial position. With a total budget of $96m in 2018/19 (see Figure 1), the county government could only spend $80 per capita per year, of which less than $28 was available per person for developmental expenditure.

After several months of data collection and analysis, UN-Habitat recommended that the county government build up its own analytical and management capacity and integrate the analytical steps of the ROSRA into its internal accounting and reporting systems, to create a more transparent and evidence-based OSR policy.

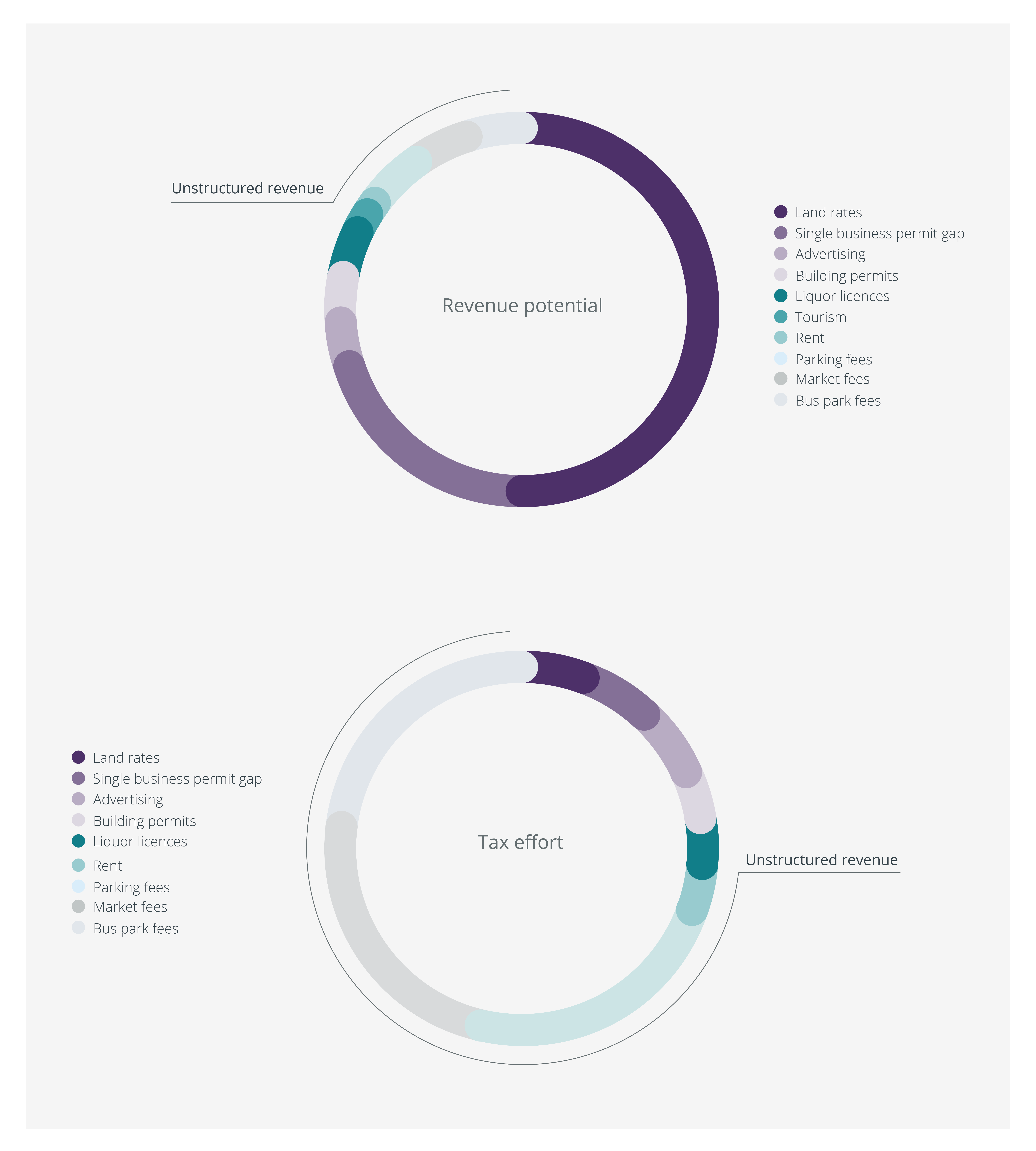

- the county government was only collecting around 19% of its total OSR potential in 2018/19

- land rates constituted nearly 40% of the overall gap between actual and potential revenue

- land rates received a fraction of the resources dedicated to tax collection although estimates of its profitability were among the highest (see Figure 2 and 3)

- unstructured revenue streams are generally difficult and costly to administer because they are collected daily rather than annually

- the overall tax system was highly regressive (see Figure 3) because of its focus on user fees – that is, unstructured revenues – and the failure of high-income groups to comply; nearly 90% of land arrears were owed by the 10% of landowners with the largest share of land, amounting to a total of 10 times the annual OSR.

The UN-Habitat findings were welcomed by the county government and described by its chief financial officer as "the most detailed and accurate analysis of Kisumu's OSR to date". There was little disagreement over the empirical data or the conclusions derived from it.

Despite this, the recommendations were not implemented. Instead, the system defaulted to business as usual, as a forthcoming UN-Habitat publication reports. The proposed reform foundered because the situation had not arisen by accident or lack of technical know-how, as the UN-Habitat team had assumed, but by design.

The OSR system was serving particular interest groups at the expense of the general public. The proposed shift away from unstructured revenues was opposed by tax collectors, who feared losing their jobs and opportunities for bribery as a result of more automated, structured collection processes. Large landowning elites would resist property taxes, since they would have large liabilities. Neither was simplifying the tax system in the interest of civil servants, who may deliberately complicate it to prevent transparency and retain opportunities for embezzlement.

The politics of OSR reform

The Kisumu case is no anomaly, and reluctance to reform OSR regimes is commonplace. After all, they are money-making machines and thus tend to be objects of considerable vested interest. Any change to a system is a politically delicate matter and will disrupt the status quo, creating new winners and losers.

The longer an inefficient system is left in place and the lower the overall adherence to the rule of law, the stronger the entrenched interests in the status quo become and the more difficult it is to make meaningful reforms. The bottleneck for successful OSR reform in Kisumu, as with most local governments in the developing world, is not lack of technical capacity but lack of incentive.

It is time therefore to position political will and leadership at the heart of OSR research. We need to better understand how to overcome vested interests in inefficient institutions, when effective policy options are chosen, how political leadership for reform comes about, under what conditions stakeholders build effective OSR institutions, and what shapes their political will.

"We need to better understand how to overcome vested interests in inefficient institutions"

Understanding the role that incentives could play and the politics of OSR reform is not only critical for optimising the relevant institutions and practices, but also to manage the trade-offs between various municipal finance interventions. Enabling access to private capital in the form of bonds, loans and public–private partnerships is commonly seen as a way to enhance the financial position of local governments that complements OSR reform.

However, by providing access to external funding, these initiatives can reduce the incentive for OSR reform and for making better use of internal resources. The sustainable financing of cities and local governments will ultimately require the development of OSR institutions and municipal finance foundations.

Gaining a better understanding of the conditions for successful OSR reform will help determine when the development of effective institutions can enhance the financial position of cities, and when it should be seen as a prerequisite without which access to external finance is inadvisable.

The majority of issues we face in international development are not a result of technical or capacity constraints. The challenge is to overcome vested interests. This is why institutions have moved centre-stage in the literature on economic development. It is widely accepted that effective institutions strongly correlate with economic performance, and likely also explain differences in economic output. It continues to be far less clear however, how these socially desirable institutions arise.

Just as with OSR systems, the question is when those involved can be constrained – or constrain themselves – not to pursue their self-interest above that of the public. Given the centrality of taxation in the literature on state building, and the close correlation of tax revenue and GDP, an analysis of the emergence of OSR institutions may also prove valuable for the broader development of good institutions.