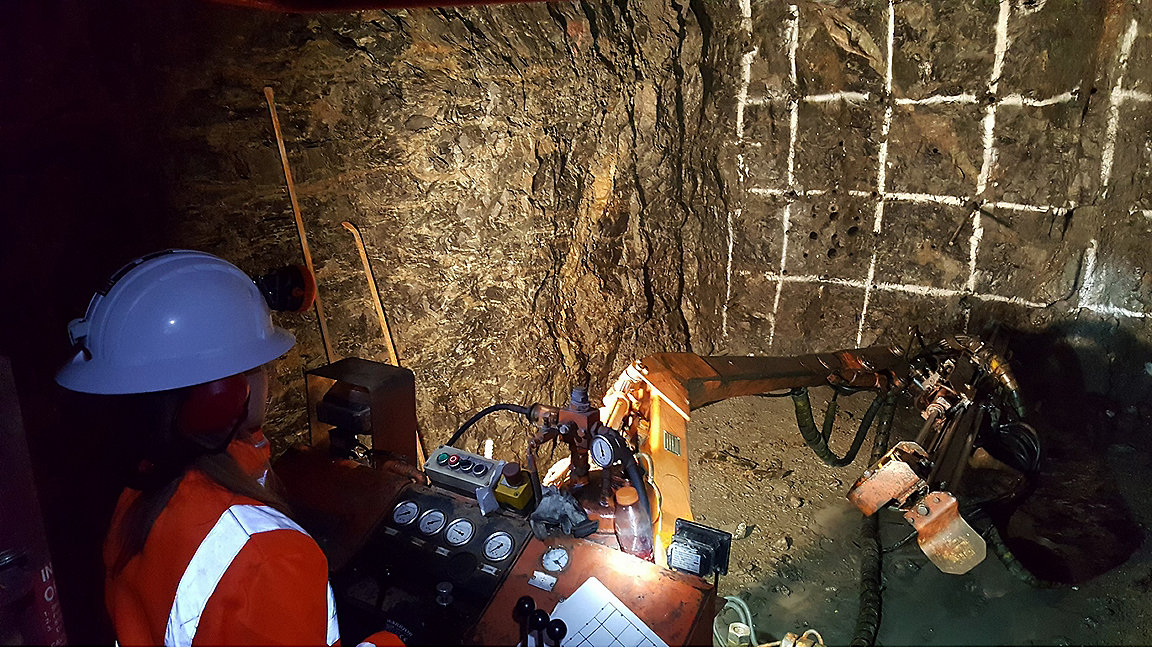

Face drilling with a single boom drill jumbo at South Crofty. © Cornish Metals/Steve Tarrant

LJ: What is the current capacity of rare metals in the UK?

Kim Moreton: The question should really be: how much exploration are we doing? Any exploration programme requires some target or certainty for those funding it.

Greater awareness among landowners and the owners of large estates could advance minerals exploration. People imagine that mineral exploration on estates would be for coal, sand and gravel, which were the traditional markets. But we're seeing more and more exploration for metals. It will be a whole other issue to set up exploration programmes that can identify what else is under the ground, and establish whether it is there in quantities that are currently commercially viable.

A lot of British expertise is deployed overseas, but exploration is being carried out across the west country, in areas of Wales and in parts of Scotland. The UK has significant known reserves of gold that continue to be mined, and more projects are in the pipeline.

Global resource availability and global supply chains have come under even greater scrutiny since the war in Ukraine, and focused attention on the UK's own resources. One critical mineral is tungsten: the hardest metal with the highest melting point, it is used in many sectors of the economy such as automotive, technology, energy and manufacturing. It is classified as a conflict mineral – mined by forced labour in certain parts of the world – and the EU and the US have identified a significant risk to supply of tungsten concentrates in the near future.

Meanwhile, the overhaul of the UK's electricity distribution system to accommodate renewable generation and mass-market electric vehicle (EV) ownership – cornerstones of the energy revolution – will require significantly greater quantities of copper, tin, nickel and other metalliferous minerals, far in excess of those currently available. The UK is therefore seeing a return to exploration and resource assessments.

And you can't mention rare metal capacity without thinking about the planning regime's capacity to handle mineral applications. Planning authorities are under huge pressure because of budgetary cuts.

Planning departments do their best. They're often faced with seriously complex, multi-layered information: water tables, complex ownership rights, long-term restoration plans and biodiversity net gain (BNG). For instance, where the site can be repurposed and restored after extraction it is possible to secure BNG in the long term. However, the pathways to achieving this are complex and require a matrix of skills.

There are skills issues too, because of the issues that a mineral proposal or developments such as the gigafactories in Sunderland and the West Midlands, which will make EV batteries, pose.

'You can't mention rare metal capacity without thinking about the UK planning regime's capacity to handle mineral applications'

To sum it up, rare metal capacity is a multidisciplinary challenge. But it can be met, and can be an intrinsic part of the revival of the UK's primary production and resource efficiency.

Chartered minerals surveyors are at the heart of the process, from identifying rights and ownership, feasibility studies and initial exploration permitting through to operations, environmental planning, royalties, closure planning and restoration. Mineral surveyors are in demand, and it's probably the most exciting time for our discipline in decades, with lots of opportunity ahead.

'Mineral surveyors are in demand, and it's probably the most exciting time for our discipline in decades'

LJ: What are the global geopolitical issues for minerals?

KM: Rare earth metals aren't actually very rare. They're quite well distributed across the planet's crust. Where they are in concentrations that are currently viable to extract happens to be in China: but China doesn't have the same environmental protections and planning considerations around extraction that we have in the UK.

Your hi-tech vehicle might have begun its life in China, with some young people digging in a giant wet, open pit to bring up tons and tons of material to process. By comparison, it typically takes a minimum of six years for an application for mineral extraction in the UK – and that's just the planning.

LJ: How are all these issues affecting the UK minerals sector?

KM: To get a perspective on this, we need to look at how everything is related. One of the side effects of the ongoing electrification of vehicles has been a lively debate about the amount of energy that's needed to extract and create new battery storage infrastructure. Some people believe that means there is no net green advantage in the short to medium term. But you need to consider the global emission scenario as well as local emissions.

One school of thought suggests the UK should retain all the rare earth elements extracted here because we produce very little of these. The EVs built in the UK aren't super-sexy Teslas, they're down-to-earth, affordable, reliable vehicles such as the Nissan Leaf. UK-built EVs currently rely on power packs and power plants manufactured elsewhere using materials sourced elsewhere. There is a huge opportunity to localise production of both.

Japanese manufacturers have always paid attention to vehicle recycling and reuse. There's a well-trodden recycling path, but there's no single manufacturing standard yet, and the variety of battery formats is a hurdle to the profitability of mass-market recycling.

The BSI has introduced PAS 7062 to promote good design, manufacturing and handling practices. EV battery pack geometry is a major consideration in mass-market automobile manufacturing, recycling and end of life, but as yet there is no convergence between global manufacturers.

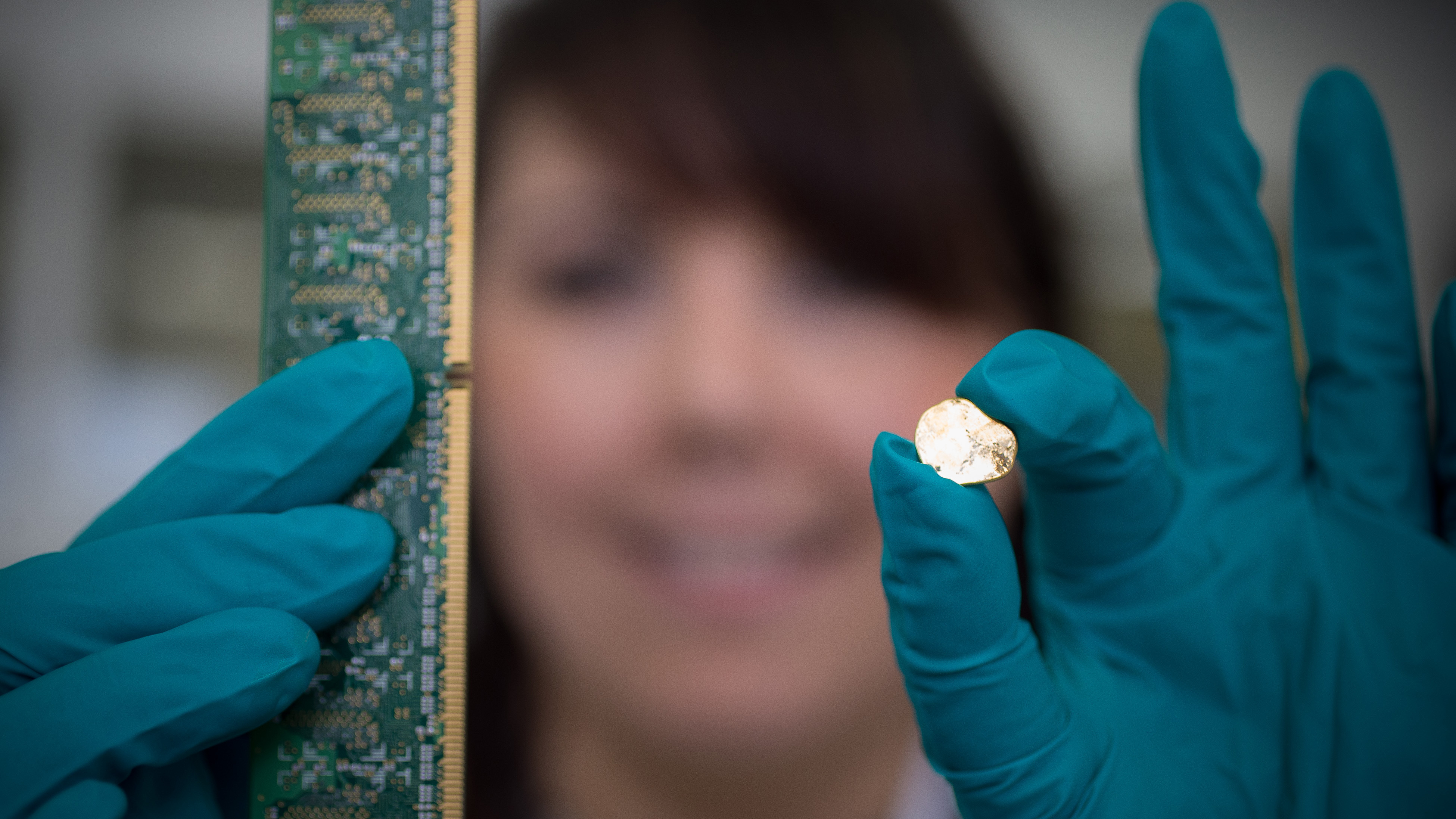

Recovery plant can boost UK skills

The Royal Mint is developing a processing plant in South Wales where the skills, infrastructure and environment favour commercial recovery of viable quantities of gold from waste electronics. This is encouraging, as the UK not only needs to protect and nurture its mineral and mining skill base, but also foster new talent in mineral processing, metallurgy and electrochemistry.

Recycling is also critical in renewable energy. Many wind turbines installed over the past two decades are reaching the end of their lives, but recycling them is not easy. The greatest difficulty seems to be with the turbine blades, vast pieces of complex, composite fibre structures. For now, the market hasn't found the best way to monetise recycling them. Capital prefers a quick return, and this part of the material cycle is not yet well understood by investors – and of course there has been easier money to be made elsewhere.

Compliance and regulation are the usual incentives for these advances. However, UK governance has proven – I choose my words carefully – somewhat haphazard and unfocused in recent years. Of course, RICS members can and should step up to the plate. I see a growing appetite from our land and mineral estate clients and operators for innovation and options to make investments and changes to meet these new challenges, despite the triple whammy of Brexit, COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine.

Another issue is whether or not the government has planned a sustainable financial model, where those who are benefiting from various tax breaks and revenues can continue to do so. There seems to be a shift in government sentiment away from onshore wind and solar, with news stories claiming that the technology is unpopular with the public. Whether this is a manoeuvre to placate rural voters remains to be seen.

The announcements about the Sunderland and West Midlands gigafactory developments are good news, though, because this builds the capacity, knowledge and skills to process materials and supply primary automotive manufacture. This hasn't really been done at scale in the UK before, except at one or two companies that until now have brought the finished components in to the country. Mineral processing to support such endeavours needs to be to be part of this strategy. In terms of bulk metals production, the UK has a single aluminium smelter at Fort William and a mothballed facility at Lynemouth.

LJ: Lithium has been in the news recently. What is it used for and why is it critical for a tech economy?

KM: Lithium’s characteristics offer high-charge density, other battery compounds are in development, but lithium is tried and tested and is the contemporary mass production preferred solution.

It's the key element of contemporary portable power storage. There is some suggestion that the current EV market is simply allowing drivers to pay for the privilege to pollute elsewhere, and some manufacturers haven't done much to counter that.

As with any new technology, EVs are expensive at the moment, and their cost is a divisive issue at a time when we're seeing huge drops in living standards.

The wider issue is whether or not there is sufficient capacity to rapidly enable all the households with EVs to charge them at home. There are probably plenty of people with a very efficient EV parked outside a large old house that costs them hundreds of pounds a month to heat.

It is key because it's the bridge between the internal combustion engine, skills, knowledge distribution centres, distribution points and EVs.

The UK's first cars were imported in the 19th century, and then produced under licence. In some ways the evolution of the UK's EV industry is following that pattern.

Based on the current trajectory of policy and investment, everyone's going to get an electric car, and lithium is an essential resource for this. The processing, manufacturing and recycling is well understood. These operations can be easily fitted into our existing automotive industry, which in turn encourages developments in mass-market energy storage technology.

There are also already healthy markets for used batteries from Toyota's Prius and Nissan's Leaf models, which are being repurposed for domestic energy storage.

LJ: What is the future of UK mineral extraction and exploitation?

KM: Demand for construction materials is increasing at the same time as the value of surface interests is going up. Surface interests are a major consideration in the exploration and development of resource extraction and of vital resource development value.

Mineral planning in the early part of this century has led to safeguarding of significant quantities of sand and aggregates in particular. Development pressures also continue to pose challenges for operators, and the lead times for planning applications aren't getting any shorter.

Mineral planning is, by necessity, complex and it requires a broad skill set. Planning departments have faced budgetary, skills and recruitment issues, so good mineral surveyors are essential to projects.

The UK government is also trying to secure the continued supply of UK fossil fuels from existing sources. The life of coal power plant is being extended and North Sea oil extraction is being reviewed to ensure energy security. A significant return to nuclear energy has been announced in the UK, in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It's focused attention not only on where our gas, coal and oil come from, but also our sources of uranium.

The $64,000 moral question is: how do we maintain some balance between where we pollute at home and where we buy our energy from? It's the dilemma of our times, and it's far too important for virtue signalling. In my opinion, there needs to be much more honest dialogue about this. Consumers are already paying a penalty for decades of heel-dragging by governments of both parties on energy supply, and the scramble to return to fossil fuels demonstrates the urgency of the situation.

'The $64,000 moral question is: how do we maintain some balance between where we pollute at home and where we buy our energy from?'

LJ: What does the sector need to be wary of?

KM: Environmental issues. Unfortunately, as with any major asset ownership, any type of extractive operation comes with a best-before date in terms of finding the balance between good stewardship and the practicalities of investment.

While there's a lot of excitement around minerals and metals at the moment – and a lot of exploration is planned – it's possible that in ten or 15 years, let's say, some other mass energy technology may come in, such as nuclear fusion or other ways of generating hydrogen. Then, unfortunately, that best-before date is up, for some investors.

While the spotlight is on our domestic resources, we need to ensure we nurture a culture that supports exploration licences for metals. We need to invest so we correctly manage extraction, communicating with all stakeholders, and making sure there are sufficient resources for meaningful restoration of sites.

Professional capacity is another issue. Degree apprenticeships and other models of learning and assessment that blend practical, academic and professional experience are so important. The UK's final cohort of mining engineering students graduate in 2024, and at the moment that's it. Even if a new programme is available from 2023, the UK will not produce mining engineers or mineral processing graduates until 2027 at the earliest. Unfortunately, universities don't seem to be interested in these disciplines – they prefer mass-participation degree programmes that attract hundreds of students in a cohort.

Meanwhile, as teaching staff from these minority disciplines retire, no one is replacing them. At Camborne School of Mines we're hoping that the University of Exeter is successful in bidding for the degree apprenticeship in mining engineering in England. We don't want the profession, or the discipline, to become invisible. The UK punches way above its weight in the global minerals industry, but the neglect of our sector's skills is damaging that.

Mineral surveying is varied, it's interesting. Few other professions include the variety of tasks and skills such as contact with your clients, the need to negotiate and be intellectually nimble, personable and persuasive, as well as the mix of technical and legal knowledge that includes not only land rights, valuation, ratings, planning and development, ground engineering, geology, but gets you out of the office on a regular basis talking to clients from an extraordinary range of backgrounds. There's nothing quite like it.

I hope at the very least we might see some master's programmes in the near future that would allow people from diverse backgrounds to qualify. One of the problems is that messaging about the career opportunities needs to be there for 13–15-year-olds, and it’s difficult to find one voice to represent the sector.

The Mining Association of the UK, ABMEC the British Mining Trade Association, Mining Education Trusts, the Institute of Materials, Minerals & Mining and industry partners have recently formed the UK Mining Education Forum, which is trying to plug that gap.

We need a wider discussion, one that doesn't stop at 'We don't want mining.' Everyone who wants a better future has a responsibility to be aware of, and to engage with, the dialogue.

Kim Moreton MRICS is chair of the Camborne School of Mines Association, and lectures in mining and mineral surveying at the Camborne School of Mines, University of Exeter

Related competencies include: Minerals and waste management, Minerals management