It is something you do every day; and as a professional working in the built environment, it is highly relevant to your working life. But how often do you actually think about walking?

For many, walking is just what happens when we put one foot in front of another. However, it is both a mode of transport in its own right as well as a part of virtually all other journeys, whether by bike, bus, train or car. It brings great benefits – for individuals, for business and for cities.

Yet we are walking less than we used to. The distance people walk has gone down by about a tenth over the past ten years. According to the Department for Transport, people in England walk an average of about four miles per week, or just less than 200 miles a year. But averages can be misleading: every month, four out of ten adults aged 40 to 60 in England spend less than ten minutes walking continuously at a brisk pace. What's more, nearly a third of all car trips are shorter than two miles. So there is potential for change.

Public Health England (PHE) is clear about the health benefits of getting every adult active every day. As little as ten minutes of physical activity at a time benefits both bodily and mental health. Persuading inactive people to become more active could prevent one in ten cases of stroke and heart disease in the UK and one in six cases of death from any cause. It could reduce levels of depression by 30 per cent and reduce the risk of dementia – now the leading cause of death in England and Wales – by 30 per cent. As PHE states, 'if physical activity were a drug it would be classed as a wonder drug'.

Having healthy streets that encourage active travel is now enshrined in government policy. A key section of the draft London Plan, the capital's spatial development strategy, is the Healthy Streets Approach, which is designed to improve air quality, reduce congestion and help make the city's diverse communities greener, healthier and more attractive places to live, work and play. The mayor's aim for 2041 is that 80% of Londoners' trips will be on foot, by cycle or on public transport.

This means that development proposals will need patterns of land use that enable residents to make shorter, regular trips by walking or cycling. Specifically, development proposals will need to demonstrate how they support the indicators developed by the Healthy Streets initiative, such as encouraging pedestrians from all walks of life and creating shade, shelter and places to stop and rest. They will also need to reduce the dominance of vehicles on London's streets, whether stationary or moving, be permeable by foot and cycle and connect with local walking and cycling networks as well as public transport. For developers, this means thinking as much about the spaces between developments as the developments themselves. It means creating high-quality, attractive public realm that designs physical activity back into our everyday lives.

The Healthy Streets Approach can reduce air and noise pollution and help combat social isolation. Having people walking through urban spaces also makes those areas safer for others and is a great social leveller. It is people on foot who make urban centres vibrant and they support economic activity. Transport for London discovered that people who walk to town centres across London spend more per week than those who come by bus, train, tube, bike or car. And employers are increasingly finding that to attract new staff, particularly millennials, they need to be based in vibrant, walkable areas. Companies are therefore starting to incorporate walkability into their building layout, with some having their offices designed to encourage walking.

Samsung's US headquarters in San Jose, California is based on a walking layout so employees are never more than a floor away from stepping outside for a walk. Google's plans for its 'landscraper' headquarters at King's Cross in London include a 200m-long 'trim trail' on the roof to enable staff to exercise. Other companies are incorporating a 'daily mile' route to encourage employees to get out for a walk; for example, Saga's group headquarters at Sandgate near Folkestone has a marked-out mile in its grounds that staff can use for a meeting or a stroll at lunchtime.

Steve Jobs, the late co-founder of Apple, made a habit of the walking meeting. Anecdotal evidence suggests that such meetings lead to more honest exchanges with employees and are more productive than traditional sit-down sessions. Getting more people walking at work would make for a healthier workforce and not just by reducing the risk of diseases linked to physical inactivity. Research also shows that absenteeism rates are lower among staff who walk and that active commuters are better able to concentrate and under less strain than those who travel by car.

Moving towards a walking world requires the transformation of our towns and cities, many of which suffer from being designed around the car. We need to place walkability at the heart of our urban environment.

The Walkable city

The Walkable City is one that puts people first and shapes itself in accordance to its citizens' needs and desires. To address the complexity of the urban issues, a variety of actions and policies is required, diversified both by nature and dimension.

The starting point is to have a vision and strategy. Urban policies, involving city plans and innovative interventions, can promote a diffused, walkable approach. But this does not have to be a lengthy strategy: Greater Manchester's recent Made to Move report aims to double and then double again cycling in the conurbation and make walking the natural choice for as many short trips as possible. The city intends to do this by putting people first, creating world-class streets for walking, building one of the world's best cycle networks, and fostering a culture of cycling and walking, and the document has 15 steps to transform the way people get around.

We need to act to provide safe and efficient transport systems and improve street networks. Examples of such measures include improving walkable connectivity, pedestrianisation, better integration with public transport, reducing vehicle speeds, improving crossings and signage.

We need to create more liveable environments, with improved urban quality and redesigned public space that prioritises people on foot. This can include re-using redundant infrastructure, improving street design and furniture, creating pocket parks, improving micro-climates and having active street-level frontages such as shops and cafes.

We can help to create a sense of place and community that encourages the active and emotional participation of people in everyday life, for example through public art, open-street events, street fairs and inclusive design. Smart and responsive cities also enable us to create playful, interactive environments, providing wayfinding systems, monitoring the city and using digital evaluation tools.

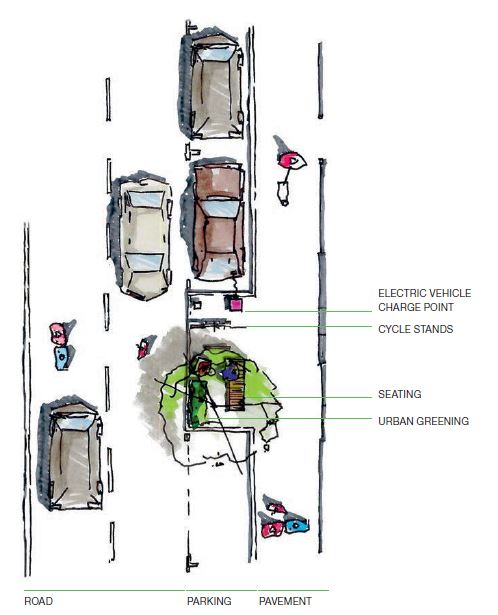

The good news is that we can design physical activity back into our everyday lives by encouraging walking as a daily means of getting around. The measures can range in size from a single parklet (see illustration) to major schemes such as the New York High Line public park, which was created from a former elevated freight-rail line. That means walkability can be improved for today and tomorrow, as well as in ten or 20 years' time.

We can all play a part to help improve walkability in our actions and decisions, as well as by encouraging walking in our businesses and creating walkable places as part of the developments we create in our professional lives. So, let's all think more about walking – and as it boosts creativity, what better way to do that than taking a walk? As Nietzsche wrote, 'All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.

Related competencies include: Masterplanning and urban design, Spatial planning policy and infrastructure