.jpg)

Green infrastructure offers significant economic, social and environmental benefits for development. Green roofs, for instance, improve air quality, provide space for social interaction and relaxation, manage storm water, reduce the urban heat island effect, and offer space for food production and wildlife habitat. While some benefits accrue to owners or occupiers and others to society as a whole, there has been increasing uptake of green infrastructure internationally.

Benefits and barriers

Green roofs and walls can recreate ground space lost to the increasing development necessary to house growing populations, and will be valuable in adapting to the higher temperatures that climate change is causing in cities.

- improved insulation and reduced energy consumption

- attenuation of storm-water flooding

- increased local biodiversity

- providing an environment for endangered species

- enabling local food production

- offering local amenity space

- provision of social space.

There are meaningful economic returns for each of these benefits, such as a price premium of around 9% for sustainability features in top-quality commercial property (Newell and Lee, 2012).

Despite these advantages, one of developers' key concerns remains the high costs of green infrastructure (Downton, 2013). Specialised knowledge and skills are needed for installation and maintenance, and this presents a major barrier to uptake. It is therefore vital to identify multiple short- and long-term performance benefits and economic and environmental values to establish the viability of green infrastructure.

Furthermore, the capacity of the construction industry to provide green infrastructure in most countries (Wilkinson et al, 2018) is still limited, and it needs to be able to supply the skills to meet anticipated future demand. These and other barriers are summarised in Table 1.

"Specialised knowledge and skills are needed for installation and maintenance, and this presents a major barrier to uptake"

| Type of barrier | Description |

| Economic |

|

| Environmental | Understanding of system maintenance may vary, affecting operational lifespan Additional water consumption to maintain Additional energy consumption to maintain Competition with other sustainable technologies such as rooftop solar thermal and PV |

| Social | Occupational health and safety during installation and maintenance |

| Technological | Structural capacity for retrofit Perception that systems are prone to leaks Durability of systems Reliability of systems and need for maintenance Access to roof for installation and maintenance Orientation/access to sunlight Lack of guidance for owners and property/facility managers Construction industry capacity |

Table 1: Barriers to green infrastructure

Source: adapted from Wilkinson & Dixon, 2016

| Type of barrier | Description |

| Economic |

|

| Environmental | Understanding of system maintenance may vary, affecting operational lifespan Additional water consumption to maintain Additional energy consumption to maintain Competition with other sustainable technologies such as rooftop solar thermal and PV |

| Social | Occupational health and safety during installation and maintenance |

| Technological | Structural capacity for retrofit Perception that systems are prone to leaks Durability of systems Reliability of systems and need for maintenance Access to roof for installation and maintenance Orientation/access to sunlight Lack of guidance for owners and property/facility managers Construction industry capacity |

The research project

We have been looking to establish the value and performance benefits of green infrastructure as part of a research project involving the University of Technology, Sydney, the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, and the Stockholm School of Economics. The project is supported by the Kamprad Family Foundation for Entrepreneurship, Research & Charity, and we are working with Swedish residential companies and developers such as Ikando Bostad and Svenska Bostäder.

The project has piloted the use of virtual reality (VR) to collect data on how people perceive and value green infrastructure in residential development. Although architecture uses various means to represent imagined spaces – such as pencil and paper, computer-aided design and 3D models – VR was chosen because it offers cost-effective, enhanced interactions and allows users to explore future environments in real time.

Potential buyers of apartments were invited to use VR headsets to explore different developments. The headsets tracked their eye movements, so time spent looking at different parts of the development could be quantified.

This was then analysed against qualitative interview data, where participants spoke about what they liked most and why. This provides evidence that when people stop to look longer, they like what they are seeing; for instance, a particular room in the house.

Our research examined what this data meant for the green infrastructure features the participants were shown. The quantitative data we collected, along with semi-structured interviews, provided a comprehensive understanding of potential buyers’ views of their views. Initial indications are that buyers do value green infrastructure and are more likely to put in good offers on property with good green infrastructure.

The data will be collated with figures on property capital and rental values to determine various degrees of willingness to pay for such infrastructure. This will enable developers around the world to prepare better-informed business cases for green infrastructure.

Value and willingness to pay

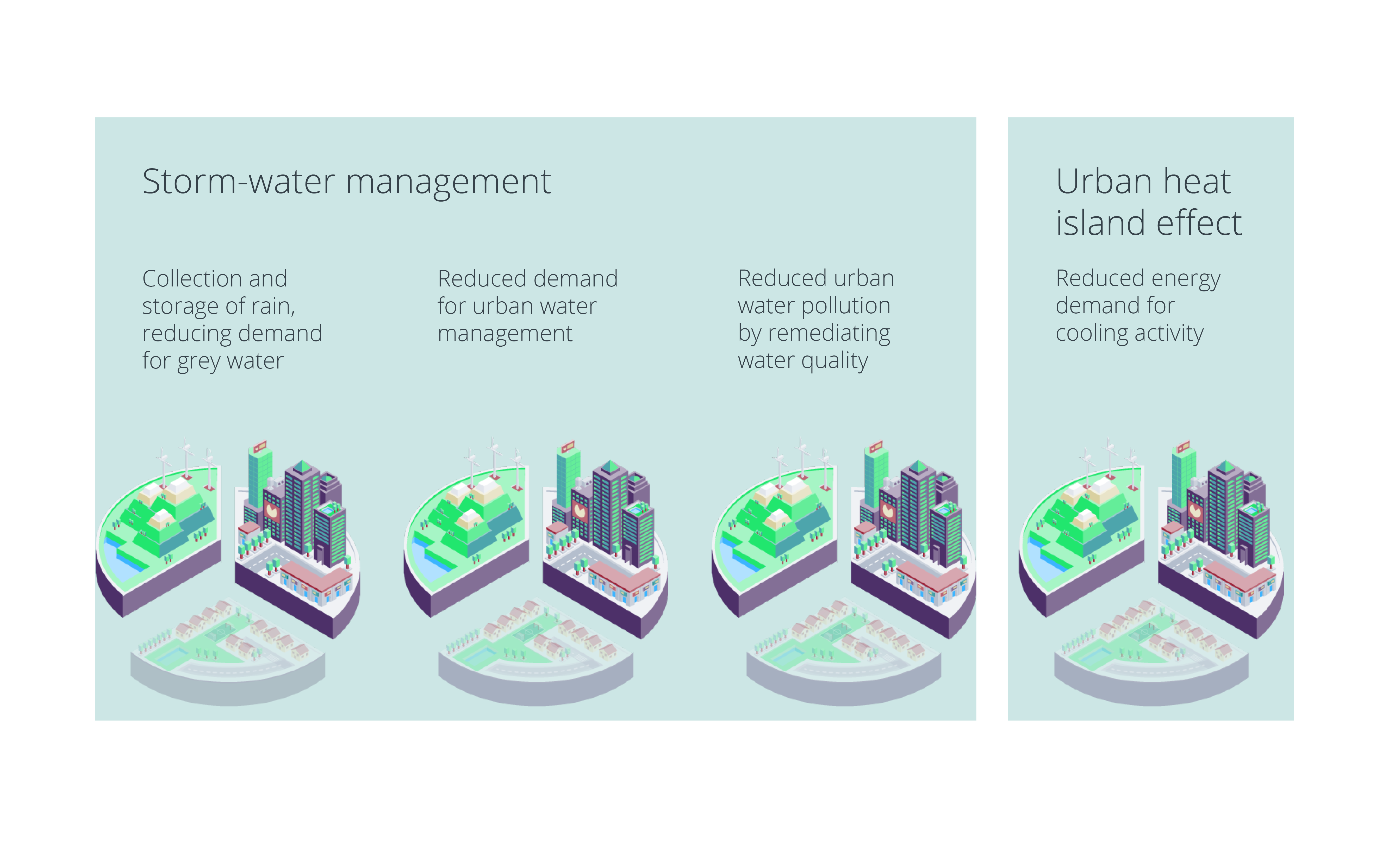

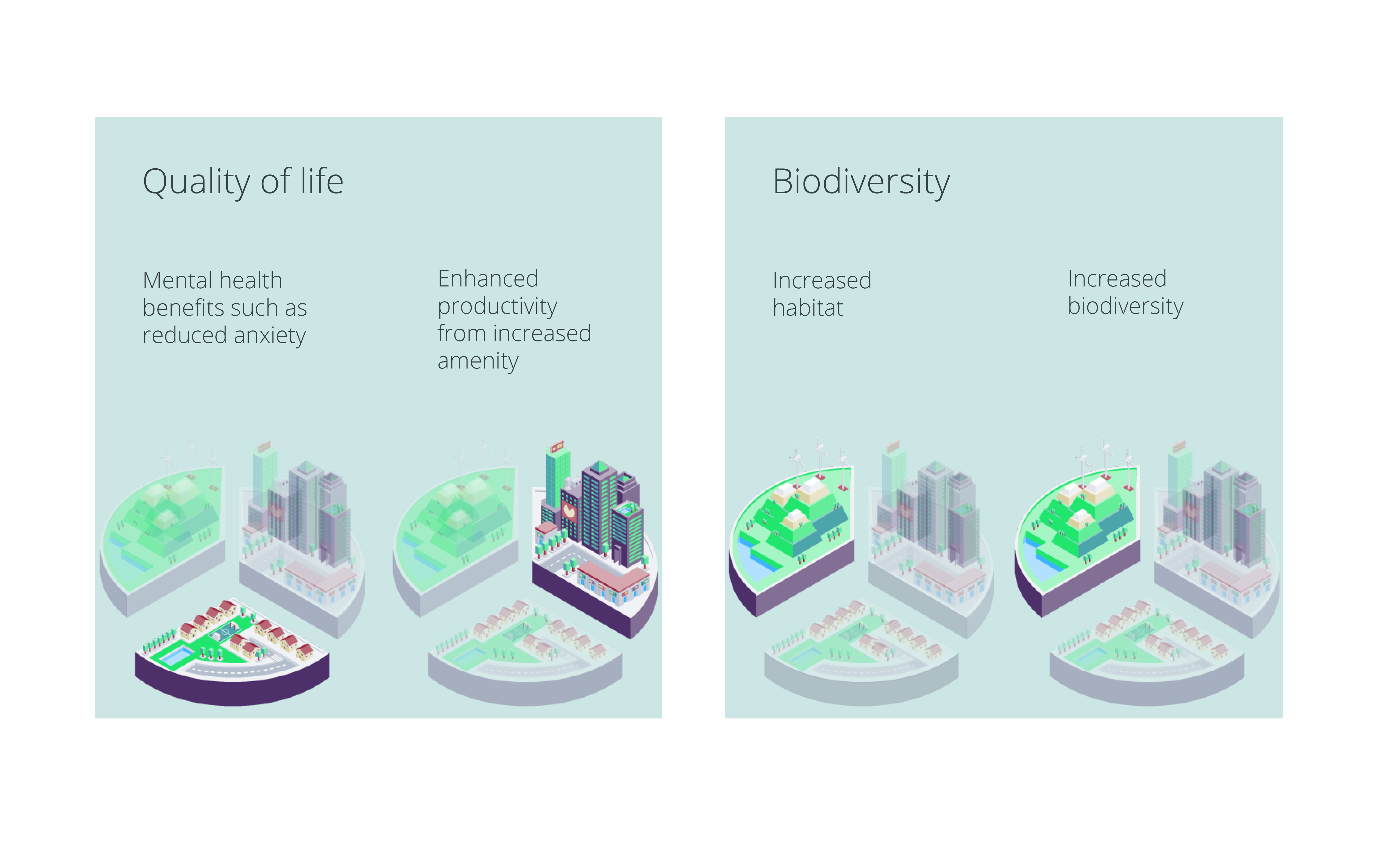

The accelerating rate of investment in green infrastructure we identified in the literature review section of the research indicates that stakeholders increasingly perceive its value. Figure 1 summarises the different kinds of value it offers.

Figure 1: Types of value offered by green infrastructure

There are various approaches to quantifying the net value of green infrastructure. The most common are cost–benefit analysis, the triple bottom line – that is, economic, environmental and social – life-cycle assessment and life-cycle costing. Life-cycle assessment focuses on the environmental impact of production, use and disposal of the buildings, while costing concerns the expense of construction, operation and maintenance over the study period. Though all methods enable the analysis of costs and benefits, none offers a reliable evaluation of trade-offs between economic and environmental performance.

While recent work to evaluate the business case for green infrastructure, such as a US General Services Administration report, has attempted to identify and quantify the economic, environmental and social value created, a more comprehensive approach is still needed.

This therefore remains a challenge for green infrastructure as owners and investors incur substantial direct costs, whereas the value is shared by various stakeholders including tenants and the local community and economy. As a result, we recommend a range of subsidies to compensate investors.

Other applications

The innovative approach of using VR technology to gain a deeper understanding of the way humans experience their environments has enormous potential in other areas of surveying practice.

For example, developers could use the technology to ascertain potential buyers’ preferences in proposed developments; estate agents could use the technology for selling or leasing property where site inspections may currently be more restricted; or tenants could visualise proposed alterations and adaptation works using VR.

The sky is the limit in the way we apply this technology in future to enhance our professional practice.

References

Downton, P., 2013 Green roofs and walls.

Newell, G. and Lee, C.L., 2012. 'Influence of the corporate social responsibility factors and financial factors on REIT performance in Australia'. Journal of Property Investment & Finance.

Wilkinson, S.; Brown, P.; Ghosh, S., 2018 Expanding the living architecture in Australia. ISBN 978 07341 4369 3

Wilkinson S.J.; Dixon, T. , 2016 Green roof retrofit: building urban resilience, Wiley-Blackwell

Related competencies include: Sustainability, Valuation