The built environment is evolving in response to a myriad of both long-standing and new shocks and stresses. Disruptive effects stemming from environmental change, societal instability, global infectious diseases and man-made threats such as terrorism challenge the resilience of our cities and their infrastructure.

To meet these challenges, national and metropolitan governments, infrastructure operators, emergency services and others have deployed a range of tools and approaches. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) – commonly known as drones – offer some new opportunities to enhance responses to, and recovery from, disruptive events in cities. The UAE’s international Drones for Good competition has showcased the diversity of potential UAV applications, ranging from power grid fault detection to organ transplant delivery.

The breadth of the possible applications of UAVs has led to over £78m in research grant funding for UAV-related projects in the UK alone over the past few years. This means that the application of UAVs to support urban resilience is only likely to increase in the coming years.

However, UAVs are a dual-use technology. Their capabilities also make them attractive to those who may intend to cause disruption, damage, or human casualties in cities. The increasing operating ranges and payload capacities of commercially available UAVs have established them as a tool for terrorists, criminals and protesters worldwide.

This dual-use characteristic has a significant implication for urban resilience: on the one hand, UAVs can facilitate response and recovery to disruption, enhancing resilience, but on the other hand, they can threaten resilience by introducing novel risks into cities.

Opportunities

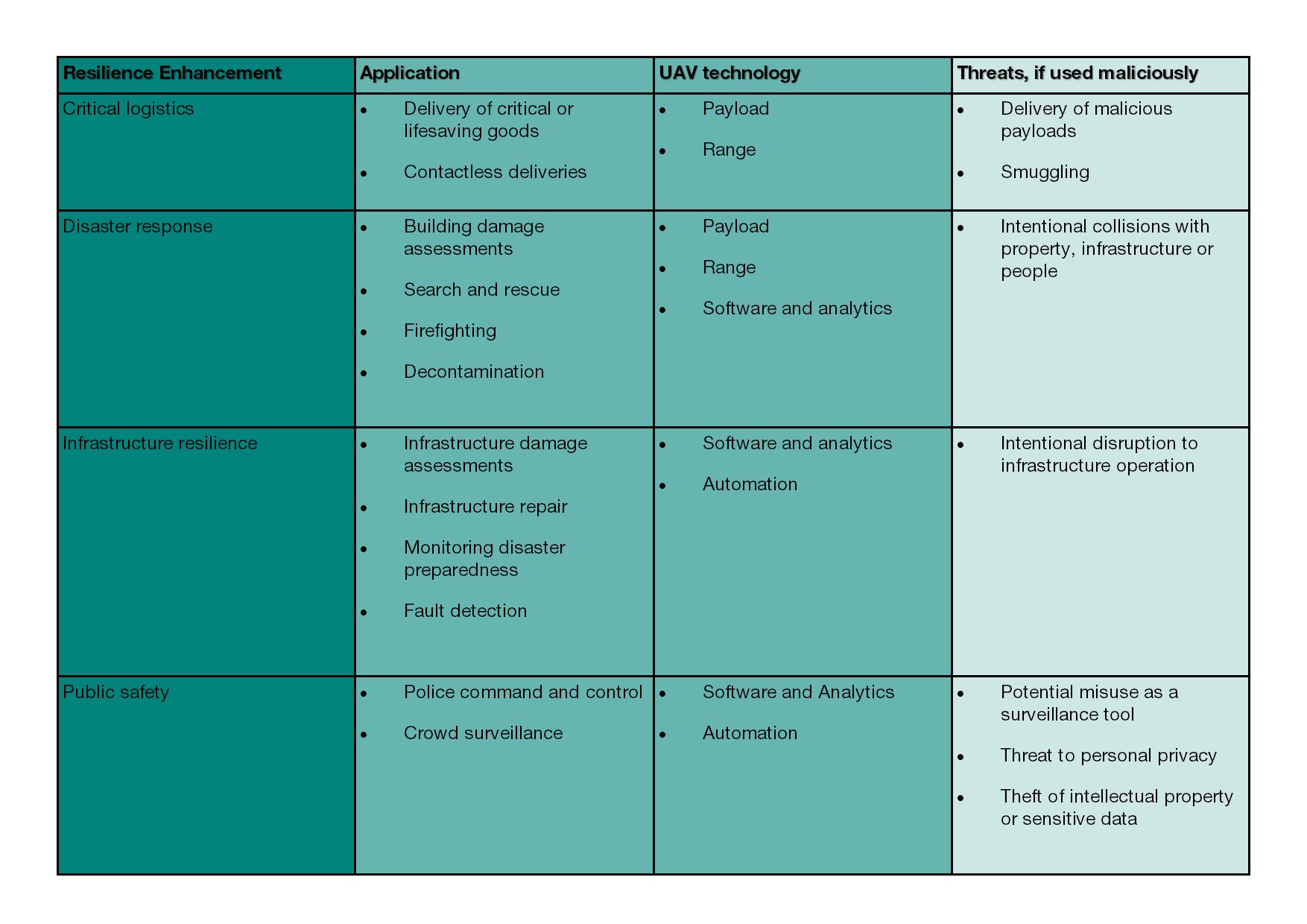

UAVs offer a range of opportunities to enhance urban resilience following shock events. The chart below summarises some of the main roles that UAVs could perform to aid responses to and recovery from natural disasters or other disruptive events in cities.

One of the strengths of UAVs is that they are free from fixed or pre-defined transport routes such as roads or railways. They can quickly access locations that are difficult to reach or have been cut-off following a natural disaster. This means UAVs can provide urgent medical supplies to local communities that are temporarily inaccessible due to a natural disaster. UAVs have already been used to deliver blood stocks, medicines, and human organs for transplant, and there are an increasing number of UAV medicine delivery services operating globally.

In April 2020, Alphabet’s Wing delivery service started making food and medicine deliveries to households under lockdown in the US due to the global outbreak of COVID-19. Likewise, two of China’s biggest tech companies, Baidu and JD.com, are using UAVs for contactless deliveries to hospitals and villages to maintain social distancing and minimise the spread of the disease.

UAVs are a particularly valuable tool to survey places that are unsafe for humans following natural or man-made disasters. Following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, UAVs were deployed to inspect and monitor radiation levels in areas that were unsafe for humans. Similarly, Californian firefighters now use UAVs to identify where fires have crossed containment lines and measure local weather conditions to predict the trajectory of the spread.

In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, UAVs are well-placed to conduct non-invasive structural surveys of potentially compromised buildings and infrastructure such as bridges or highways. Additionally, given their ability to survey a lot of ground quickly, UAVs provide an efficient means of conducting a search and rescue mission for missing or trapped persons. This capability has already been utilised by the emergency services in the UK. Finally, in Spain and China, crop-spraying UAVs have been repurposed to disinfect public thoroughfares to remove traces of COVID-19 in 2020.

UAVs provide opportunities for infrastructure operators to monitor and manage their assets by detecting faults. UAVs lend themselves well to surveying networks of infrastructure that span large sites or routes such as power grids, oil and gas pipelines, and alert maintenance crews to specific sections that may need repair or maintenance. This capability is likely to require a UAV to be permitted to fly beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS).

In the future, such an application could also extend to monitoring the disaster preparedness of infrastructure such as flood defences that protect an urban area located on a flood plain or near a body of water. One example is the Seychelles, where major national infrastructure and population centres are located on the coast. UAVs have already provided a low-cost solution to help manage the Seychelles’ coastal risks and develop the country’s national coastal management strategy through mapping of coastal erosion, infrastructure networks, and ecosystems.

Finally, UAVs offer benefits in enhancing safety in public spaces by providing the police and emergency services with a tool to monitor the size and profile of crowds and direct limited on-the-ground security personnel to the point of greatest need to address potential crowd disturbances or unsafe crowds.

Risks

There is, however, a flipside to UAV applications that enhance resilience. Their capabilities and characteristics also make them attractive to malicious actors. UAVs offer these actors a novel way to evade and circumvent traditional security systems, such as fences, gates, or guards by flying over them.

The payload capacity of UAVs has already been exploited by terrorists in Iraq to carry threat objects such as grenades to attack Iraqi security forces in Mosul in 2018. Furthermore, UAVs were reportedly used in the September 2019 attack on Saudi Aramco’s oil processing facility at Abqaiq, Saudi Arabia.

The attack ruptured fuel storage tanks and caused fires at the facility, suspending operations and temporarily dropping the kingdom’s oil production. Likewise, criminals have exploited the ability of UAVs to carry goods. In 2018, a UK gang was arrested for flying over £500,000 worth of contraband into British prisons.

UAVs have also been used to intentionally disrupt operations at infrastructure assets. In 2018, one or possibly multiple UAVs caused mass disruption over several days by simply flying near and over London’s Gatwick airport. This action affected over 140,000 passengers and 1,000 flights. This event inspired environmental protesters to threaten to use this tactic to disrupt Heathrow airport’s flight operations in 2019.

The increasing sophistication of audio-visual sensors mounted on UAVs, combined with facial recognition software, could lead to infringements of personal privacy, the theft of intellectual property or collection of sensitive information about property and infrastructure. In recent years, unauthorised UAV surveillance over movie sets, new product tests and commercial offices has been reported, which shows that this is a very real threat to the commercial world.

What does the future hold?

Given the fast, upward trajectory of UAV technical development, it is easy to imagine a future where the skies above our cities are filled with UAVs conducting a broad range of tasks. Advancements in battery power will enable UAVs to fly further, faster, and for longer. Developments in artificial intelligence are likely to enable multiple UAVs to perform tasks with minimal human direction.

These and other advances will open the way for new opportunities. Imagine, for instance, a swarm of UAVs working together to repair or reconstruct damaged buildings or infrastructure. With these new applications, new risks will also evolve beyond what we can identify today.

The proliferation of UAVs seems almost inevitable given their wide commercial application, and in response, governments are legislating and regulating to control their use. The UK’s so-called drone code is one example of regulation designed to restrict the use of UAVs by the public. However, as UAVs develop, the regulatory environment governing the use of UAVs will evolve too, which is likely to change the application of UAVs to enhance urban resilience.

The dual implication that UAVs poses for resilience highlights that UAV-related risks should feature in national and city resilience strategies. This can be done by integrating UAVs as a tool to help manage responses to disruptive shocks, by purchasing a fleet of UAVs as part of a wider resilience strategy for instance, but also by considering them as a potential risk and agitator of existing risks. As the global COVID-19 outbreak has shown, robust resilience planning is essential when mitigating novel risks. UAVs will have their part to play in making our future a resilient one.

Drones: applications and compliance for surveyors insight paper

Drone use ground rules Built Environment Journal