The principles of the circular economy have an important role in reducing waste when offices are vacated. A recent survey carried out by researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) therefore explored attitudes towards the circular economy, and what needs to be done to increase the implementation of its principles in office strip-outs in Australia.

In 13 interviews with owners, leasing agents and negotiators, builders, sustainability consultants, furniture logistics and quantity surveyors, 77 per cent of interviewees were found to have a good understanding of the circular economy; however, while the remaining 23 per cent understood that strip-outs generated waste and that this has negative impacts, they were not aware of the term circular economy. For 46 per cent, an ideal solution would be zero waste. Most respondents expressed the view that, ideally, all fixtures and fittings would be re-used, repurposed or recycled with no landfill, correlating with the definition and three principles of the circular economy as expressed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

Regarding make good, the Australian process analogous to dilapidations, all respondents stated that the most common outcome was completing the strip-out and returning the premises back to base build. All confirmed that owners take responsibility for making good in at least 75 per cent of strip-outs. Typically, building surveyors work with owners or tenants to negotiate, draft and prepare a claim, usually six to nine months before termination of the lease. Once the scope is agreed, tenants and landlords reach a financial settlement that can reduce the waste associated with services: when the landlord takes responsibility for make good in this way, they can negotiate with incoming tenants and encourage them to use existing services, carpets and so on. Although this is beneficial for services, partitions, carpets and ceiling tiles, it does not reduce furniture waste.

Ten interviewees stated that lead time and the time taken to complete strip-out together represent a major barrier, and both are key to ensuring the re-use of furniture. To enable furniture to be rehomed, an inventory of all of it and its re-use potential is needed. Even when early settlement is reached, consultants are not given time to complete inventories because tenants are still using the space. There is generally insufficient access time during strip-out to organise re-use or recycling of the furniture on site.

Eighty-five per cent thought tenants were interested in sustainability, although motivations varied: 48 per cent thought tenants were genuinely concerned, 20 per cent thought interest was superficial, while 24 per cent thought tenant interest stemmed primarily from the prospect of saving money. Large landlords focused on sustainability, with mid and lower tiers not so interested. Our research revealed that tenants engage with waste because it's visible. Lease duration correlates with interest in sustainability; longer leases equal greater attention. Most tenants want fit-outs to look good for minimum cost, whereas premium tenants already include sustainability in their operations.

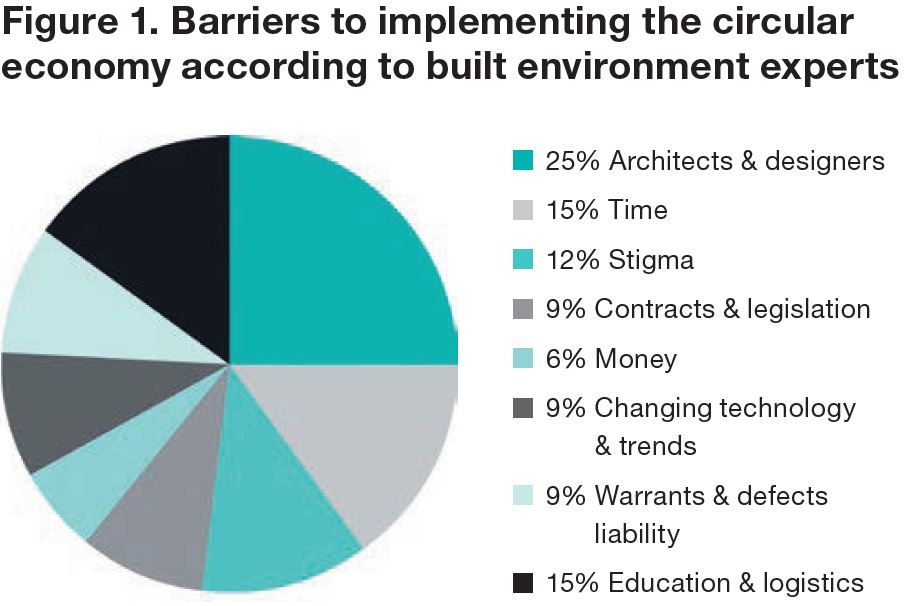

Perceived barriers to sustainable strip-outs are the lack of mandatory waste targets; corporate branding overriding the possibility of re-use; a lack of skills and knowledge in fitting-out to circular economic principles; a shortage of places to recycle; designers promoting new furniture; the stigma attached to used furniture; the inconsistent quality of waste that is re-used; technology development; and changing tastes in fit-out design. Other barriers identified were lack of cost savings; time; lack of warranty; concern that builders may make less money; and a lack of tenant awareness.

Difficulties with access to the tenancy after expiry, goods lifts, designing products for disassembly, and architects' or designers' relationships with suppliers also featured. The biggest barriers are education and logistics, architects and designers, time and stigma. Eight themed barriers are highlighted in Figure 1.

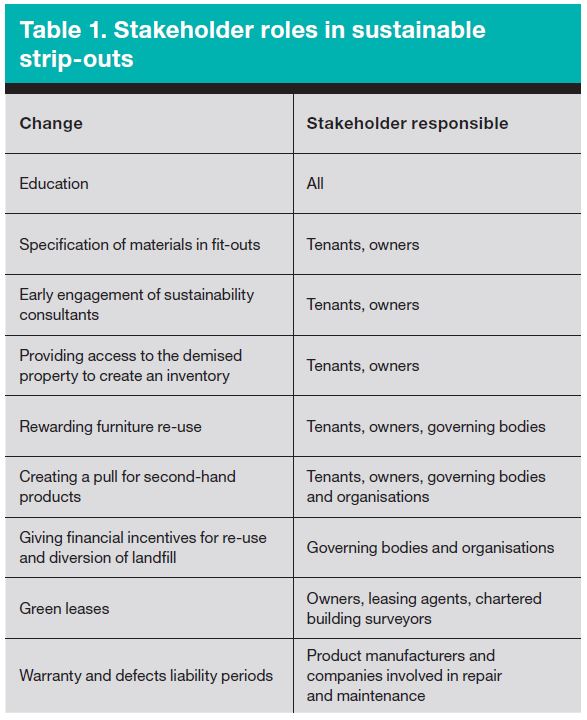

Suggested changes to overcome the barriers in Figure 1 include:

- educating tenants and architects on making sustainable choices

- specifying re-used materials in fit-outs; if not used, readily recyclable products with limited materials should be selected

- selecting materials that can easily be disassembled

- engaging sustainability consultants early so there is time to rehome materials

- ensuring sustainability consultants and those responsible for rehoming furniture have access to create an inventory at least two months before lease-end

- rewarding demolition contractors or tenants for re-using furniture

- creating a market for second-hand products; though this is reflected in the interior rating tool of the Green Star sustainability certification scheme, more needs to be done to engage A-grade tenancies that are not interested in obtaining such a rating

- providing financial incentives for re-use and diverting waste from the landfill stream

- green leases with sustainable material procurement guidelines for re-using strip-out waste

- providing warranties and defects liability periods on re-used services and furniture.

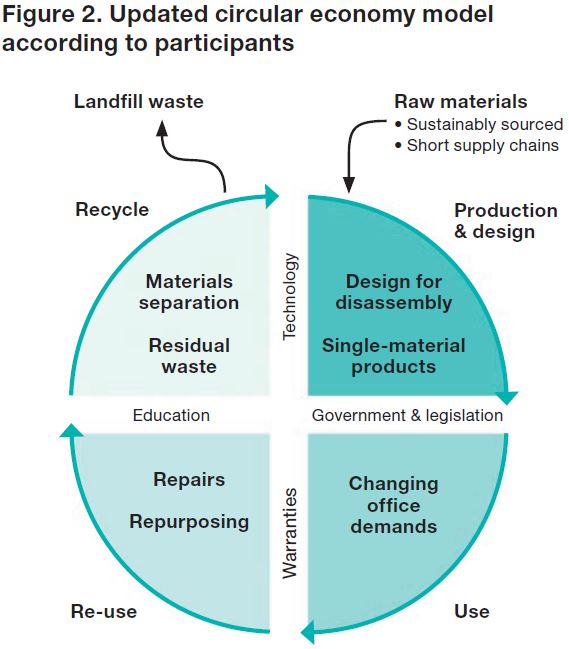

Through discussions, it was found that the theoretical model for the circular economy has limitations in practice for numerous reasons, including conflicting stakeholder wants and needs, market barriers, lack of incentives, the changing nature of fit-out design, contracts and government legislation. As such, an updated model was created, as seen in Figure 2.

All the main stakeholders need to collaborate if circular economic principles are to be successfully adopted, and owners and tenants should work together to ensure that materials are procured sustainably. As far as tenants are concerned a fit-out is transactional, only completed every seven years on average and as such most are unaware of take-back schemes or access to sustainable products. Cooperation with owners will help them improve fit-out design.

Early communication is key to allow owners to understand tenants' needs and explore opportunities to re-use parts of existing fit-outs. This can be financially beneficial for all. Communication is also necessary when coordinating the make-good process. If the owner is responsible, a furniture inventory should be produced at least two months before lease-end.

Leasing agents and owners need to work together to lease spaces without the requirement of making good to a warm shell, that is, a base building with a ceiling grid and floor covering, and all holes filled. To improve strip-out waste separation, green clauses should be incorporated into new leases. Finally, communication between builders or demolition contractors and owners is vital when seeking to re-use, as builders need adequate time or a financial incentive to take on used furniture.

If we are committed to reducing waste and implementing a circular economic paradigm then we, collectively, need to adopt the changes outlined above.

Lorna Hennessy BEng is a graduate engineer at Arup and a UTS alumna lorna.hennessy@arup.com

Related competencies include: Property management