Having considered the risks of exposure to radon in a previous article, surveyors need to be alert to homes that make it easy for the gas to enter after it is released from the ground. This includes older housing stock in areas of high radon concentration, typically Victorian or Edwardian properties that have suspended timber floors, cracked walls and foundations, cavity wall voids and so on.

Properties built before 1910, which might have coal cellars or basements, are extremely vulnerable to radon gas entering through gaps in floorboards or between skirting boards and solid brick walls. However, modern properties with cavity walls are also at risk.

A common problem is poor-quality retrofits. For example, a timber floor may have been removed from an old property and a solid floor installed, but the damp-proof membrane under the floor has not been properly linked to the original damp-proof course in the wall. This results in a gap between the two through which radon can pass. This is similar to a moisture path but may be even smaller, as radon has a much lower density than water vapour.

Practical actions

A common solution – especially for new builds but also some existing properties – is to install a sump system underneath the property. This is linked to a tube that vents outside the building.

There are also externally vented miniature sump systems, where ducting goes inside under a timber suspended floor, for instance, to extract radon. Other types of sump include those with fans to help move air away from underneath the habitable space, and passive systems that naturally vent the area below the property.

Apart from sumps, other possible responses include improvements to natural underfloor ventilation, such as subfloor air vents; again, these are similar to moisture mitigation measures. Additional low-level vents might need to be installed, particularly in areas with high concentrations of radon gas.

Mechanical underfloor ventilation systems are also a common solution, and include machines that increase the internal air pressure, bringing in air from the outside and so forcing the internal air out through trickle vents.

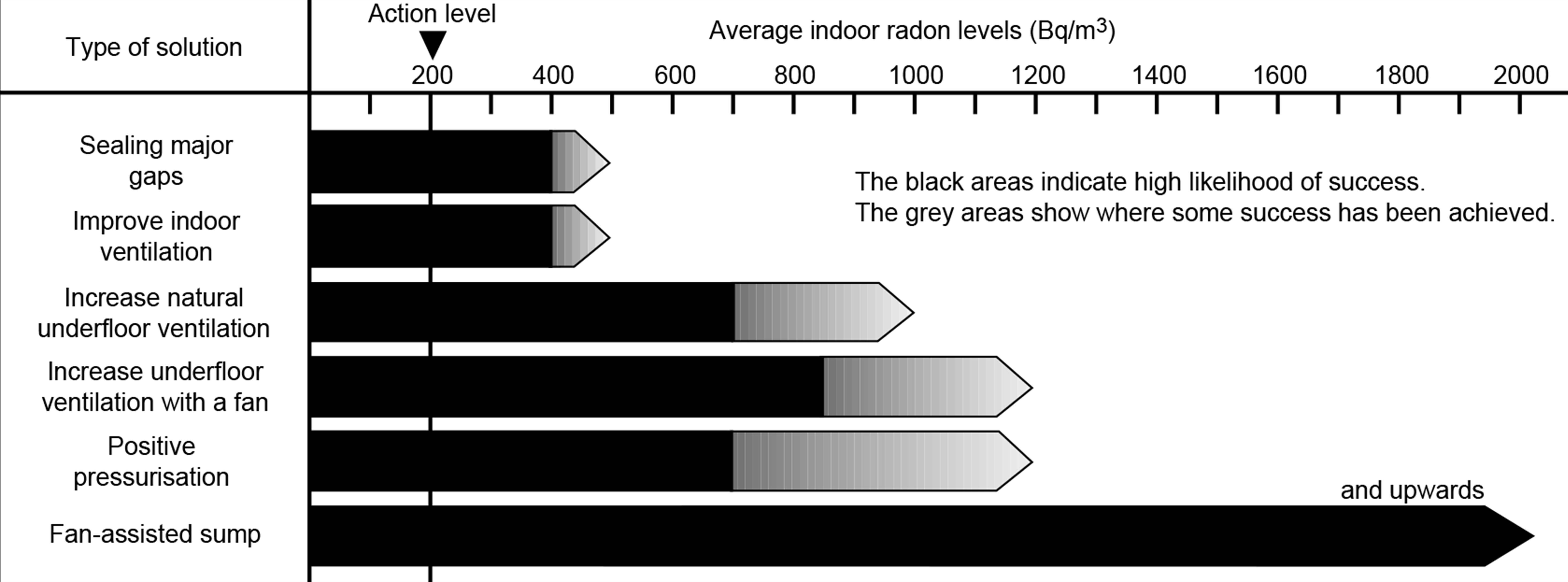

Beyond these technical approaches, simple steps can be taken such as sealing a floor. The BRE has produced a useful guidance sheet on the likely effectiveness of different measures (see Figure 1), such as covering the floor with a seamless vinyl covering or using a paint-on system. However, paint-on membranes can break down after several years, which will increase the risk of radon ingress.

It is important to remember that suspended solid floors in older homes didn't include damp-proof membranes, which means that they are not only vulnerable to moisture transmission but also radon.

Making ground-floor rooms gas-tight is almost impossible – a ground-supported solid floor improves the odds, but only if it uses a membrane. A physical damp-proof membrane that is about 1,200-gauge (as per the requirements of Approved Document C) and properly linked to the damp-proof course is sufficient to stop radon gas, but may still require the addition of any combination of the above mentioned options.

Another simple approach is to ventilate a property, using not only extractor fans and trickle vents in windows but also by opening windows after a shower or when cooking, which will dispel vapour-laden air as well as dissipating radon gas.

An underestimated danger

A 2018 article in the Journal of Environmental Radioactivity that studied radon in Northampton, UK, detailed some critical recommendations and observations. Findings included that concentrations may exceed the action level in areas of high radon concentration, where tests should be carried out in new homes in once they are occupied. The study also showed that there was little awareness or concern among new homeowners about radon and its risks.

Radon can move around our homes where nobody can see it, smell it, touch it or identify it. While testing for radon is cheap and straightforward and remedial works are not overly invasive, raising public awareness is one of the most significant challenges. Radon might be a noble gas, and as such is inert and odourless, but should still be considered an invisible killer.

Radon and COVID-19

A recent study monitored homes across Cameroon for 3 months during a COVID-19 lockdown. The aim was to estimate the effects of the lockdown on inhaled doses of radon and the associated cancer risk.

Cameroon is a good location for a radon study because it has uranium-bearing sedimentary rock formations and extensive mining activity, with high radon concentrations across the country as a result.

The study used E-Perm Electret, Raduet and Radtrak radon detectors, and found that 80% of dwellings in 2 regions – Poli and Lolodorf – had radon concentrations above the World Health Organization (WHO)'s reference level of 100Bq/m3.

More than 50% of the dwellings in Lolodorf recorded radon concentrations in excess of 300Bq/m3. Other areas, such as Bakassi, had dwellings with radon levels of 1,280Bq/m3. The study calculated that the average radon exposure time at home over 3 months was 2,160 hours.

The report concluded that the extra time spent at home due to COVID-19 increased the risk of certain cancers, particularly lung cancer. It is predicted that there will be additional fatalities due to the greater exposure to radon gas.

The study provides a warning for occupiers spending more time at home due to the COVID-19 restrictions imposed in areas where there are high concentrations of radon.

Related competencies include: Building pathology, Housing maintenance, repairs and improvements, Inspection, Legal/regulatory compliance, Maintenance management