Cujus est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos – Latin for 'Whoever's is the soil, it is theirs all the way to Heaven and all the way to Hell' – is the classic introduction to airspace in lectures. However, the practical application and importance of the concept can sometimes get lost on busy property managers.

While English property has not developed a market for buying and selling air development rights, the concept that the owner of the land also has a controlling interest in the space above it or the building sited there is still sound. It is therefore perfectly possible for an owner of airspace to find themselves in a significant commercial negotiation with neighbours about the right to construct above their property.

The airspace can be a source of immediate income generation, and even be the key to securing the longer-term development potential of the asset itself. Mature players in the property market have a long tradition of defending and profiting from the control of airspace above their key urban holdings.

Although the complexity of increased height and massing on a development site has made upward development potentially unattractive in the recent past, this is now changing and becoming more appealing on both commercial and residential units. In part, this is due to the recent expansion of permitted development rights (PDRs) – which may have been missed by some practitioners, understandably distracted by the global pandemic.

The Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) (Amendment) (No. 2) Order 2020, which came into force on 31 August last year, amended the General Permitted Development Order (GPDO) by creating four new PDRs, classes AA to AD. Each class allows for the construction of one or two additional storeys, consisting of new flats, on top of the highest existing storey.

Class AA also allows for 'development within the curtilage of a dwellinghouse' under Part 1 of Schedule 2 of the GPDO. This enables homeowners to extend existing homes of two or more storeys by up to two additional storeys, or add one storey to a one-storey home.

Airspace access

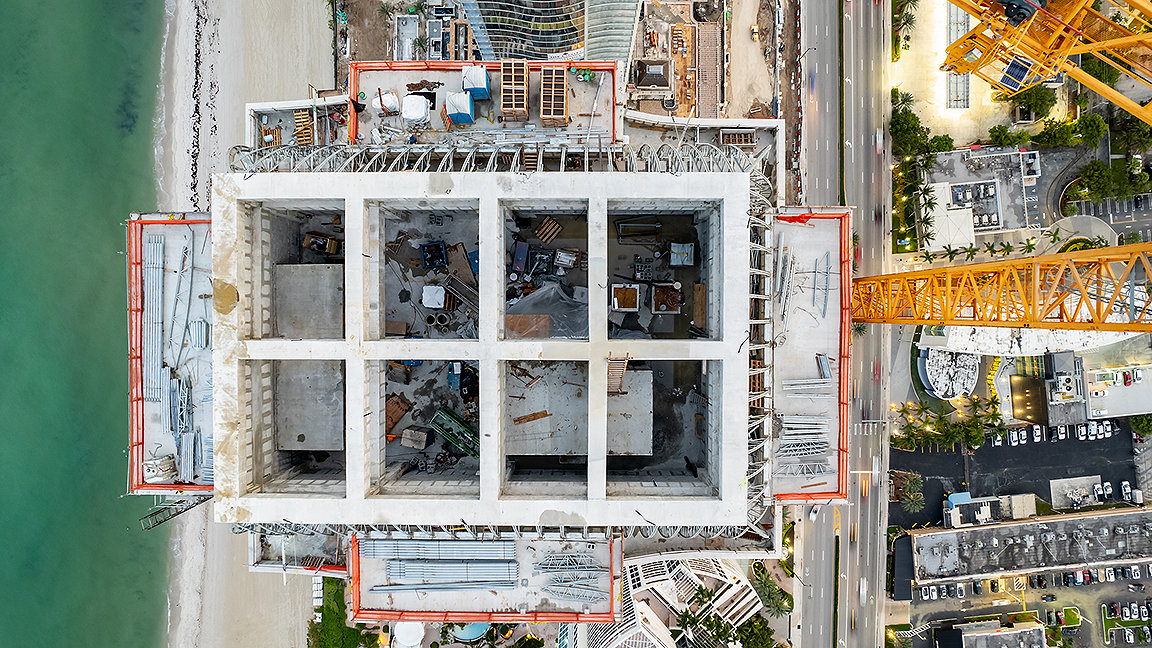

Properties on small or enclosed urban sites are likely to need entry into neighbouring airspace for scaffolding, works access and tower cranes. Once the activity crosses the boundary, the rights of the airspace holder are triggered. If they wish, they can even prevent access altogether because this is considered a trespass. That is when negotiations will probably become necessary.

What is an airspace owner likely to want in terms of consideration? Will a financial premium be requested, or would the neighbour prefer a reciprocal release of future access rights so they can work on their own development? It seems there are points of common confusion or misdirection that have led to certain regularly surfacing myths.

The first is that where a scheme enjoys PDRs, the work taking place above has effectively been approved by the government and access is therefore permitted. However, this is not true. The granting of permitted development simply has the same legal effect as planning permission, and does not override private ownership rights held by a neighbour. Therefore, scaffolding and access for cranes and workers are still private matters that need agreement in the form of a licence or deed.

The second myth is that developers who have been in the business for decades believe they do not have to negotiate access with a neighbour because they have never done so in the past. Again, this isn't right. Just because previous clients have been poorly advised or unaware of their rights does not excuse or override the fact that your present client's neighbours, who may be professionally advised by an RICS member, are not fully aware of their ownership rights and the need to agree access to their neighbours' airspace.

The third myth is that asking for a licence or deed is aggressive and unneighbourly. In fact, documenting consent in a written agreement protects both the owner and the neighbour, such that only a poorly advised developer will seek undocumented access for construction works, however minor. A licence confirms and records the terms of the agreement, obligations for repair and reinstatement of damage, insurance and the extent of the duration of the grant. Insurance is a key component, and should be extended to cover areas beyond the boundary of the site.

Development is a commercial business activity, and the parties should approach the task with an appropriate mindset. Holding one owner to ransom is rarely in either party's long-term interest, and a well-advised owner should, through their property manager, be a willing negotiation partner, provided the access request is supported by reasonable provisions in terms of licence, insurance, premium payment and reciprocal development access, as relevant.

More typically, when a developing party is refusing to negotiate it is they who are the aggressor, seeking to avoid engagement and force or bully access without meeting standard terms. They are likely to be subject to legal action.

The fourth and final myth is that by the time you get an injunction it will all be over. An injunction can actually be sought and obtained quickly, and property managers should have a list of knowledgeable chartered building surveyors who specialise in neighbourly matters and can help with expert reports and evidence when difficulties are encountered, or where development starts in airspace without agreement.

Indeed, larger funds and trusts with multiple assets now have specialist neighbourly matters surveyors on call ready to support legal action in the event of an emergency. The RICS Neighbourly Matters Scope of Service, due to be published next year, will help define the requirements for appointment.

Once appointed, the chartered surveyor can inspect the site, confirming the trespass and airspace violation. Their subsequent report will help the client's legal team submit the necessary court papers. Most competent surveyors can prepare such a report swiftly, and injunctions can then be obtained in a very short period of time – in some cases within hours.

Other airspace issues

It is sometimes possible for building works to take place without needing access, even though the activity or construction itself is near or on the boundary. In other instances, access can be granted through appropriate use of the Party Wall etc. Act 1996, as explained in the current edition of Party wall legislation and procedure, RICS guidance note. If a party wall award is in place and the detail of the access is defined, property managers should therefore ask to be made aware of any relevant documents.

When access is required to existing buildings, an order can be obtained under the Access to Neighbouring Land Act 1992. Although this is a cumbersome piece of legislation, it does enable entrance to an adjoining property for maintenance and repair in some circumstances. This can be a costly option, but is nevertheless a way to force an unwilling neighbour to provide access.

If this is a possibility then those advising on appropriate consideration or licence sums should also consider the potential use, by the repairing owner, of access provisions in the 1992 Act, and perhaps lessen the requests to sums likely to be considered appropriate under its terms.

Activities at or close to the boundary should also be carefully considered, for instance when neighbours create boiler flues in a flank wall. If a flue is drawing and venting from and into your client's airspace and goes unchallenged for a period of time, then the boiler may have acquired an easement of air.

A property manager aware of such an interference should note that this possible easement may mean the neighbour could stop any potential future development that would obstruct the operation of the flue, or demand costly changes to maintain its use. Therefore, it is important both to negotiate and accommodate the use, but also protect your client's future rights by agreement.

In a similar way, windows created at the boundary facing across the airspace will if left unchallenged acquire a common law right of light via prescription. But this is easy to stop: just approach a specialist RICS surveyor, and consider service of light obstruction notices under the Rights of Light Act 1959.

If there oversailing features on a property such as flues, windows and fire escapes, they can be regularised in a deed of grant. This can be negotiated and recorded by surveyors, and the features then remain in place for the term of the grant. When the party accepting the oversail for a term or period later comes to redevelop, they can thus ensure that any barrier to doing so – namely, the oversailing feature – can be removed.

Property managers always need to be thinking about the future development potential of a site, and protecting it from encroachment or burdens that in the long term will devalue the client's property.

'Activities at or close to the boundary should also be carefully considered, for instance when neighbours create boiler flues in a flank wall'

Andrew Thompson FRICS is senior lecturer in building surveying at Anglia Ruskin University

Contact Andrew: Email

Michael Cooper FRICS is director, head of neighbourly matters and building surveying, at Cooper's Building Surveyors Ltd

Contact Michael: Email