At the end of December, after many fraught months of negotiation, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, was at last able to welcome a trade deal with the European Union’s largest trading partner, China.

For the first time last year, the mainland wrested the title from the United States as $709 billion flowed between the EU and China during 2020. On the Chinese side, President Xi Jinping cleared negotiators to make enough concessions to ink the deal by year-end.

The deadline was important to China since a new US presidential administration was about to take office. The incoming Biden administration had voiced its disapproval of China, and it was unclear what course of action President Biden would advise after the antagonistic approach to trade with the country under former President Donald Trump.

Freer trade with the EU could be a boost that has come at a vital time for Hong Kong. Its economy had started slowing in 2018, even before the city was wracked by protests and the city slipped into recession in mid-2019, months before the COVID-19 pandemic. A year of pro-democracy protests in 2019 exacerbated a slowdown in trade and services, caused by many multinationals becoming keen to diversify away from China for their production as higher US tariffs on Chinese-made goods and services kicked in.

Professional services – banking, accounting, law – supporting China’s enhanced trade with Europe are sure to be run out of Hong Kong. But, in February, the latest figures at the time of writing, Hong Kong’s Grade A office-space market saw a record amount of space surrendered, at 1.77 million square feet. That’s the highest level ever recorded, according to Jones Lang LaSalle. It brings Grade A vacancies to 9.3% citywide, and a startling 7.5% in the highest of high-end locations, Central. Meanwhile, the shining skyscrapers that have replaced the “godown” warehouses in East Kowloon stand 14.3% empty. Central’s vacant space stands at a level last seen in 2004, during the last major recession, and the recovery from the original SARS.

But will the EU-China trade deal ever come into effect? That’s far from certain after China and the EU slapped each other with reciprocal sanctions in March, over labour and human-rights standards in Xinjiang.

It will also never pass if Hong Kong activists have their way. The EU trade agreement requires ratification by members of the European Parliament. In mid-March, they were being lobbied hard by 24 Hong Kong activists not to approve the pact. The day before the Hong Kong activists delivered a letter to that effect, China’s parliament, the National People’s Congress, had voted to approve new laws to make sure only Chinese “patriots” could be elected to office in Hong Kong.

It is the second year in a row that the National People’s Congress has laid down the law on Hong Kong, without the input of any Hong Kongers. In 2020, the Chinese legislature approved an unpopular National Security law, outlining crimes of treason, sedition and secession in the city which led to mass protests. Since its enactment, many pro-democracy politicians and activists have been charged, either under the new law or under rarely used legislation. All the pro-democracy members of Hong Kong’s legislature, the Legislative Council, have resigned.

The political clampdown is seeping into the popular psyche. In total, 21% of Hong Kongers – or 1 in 5 – plan to leave Hong Kong permanently, according to a March survey by the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute. Most have yet to actively prepare to do so, but the trust of Hong Kongers in the city’s political and economic future is not strong.

The same survey, conducted from March 15-18 of 5,697 Hong Kongers, finds that 65% of citizens lack confidence in the city’s political future, with a similar number saying they do not have faith that personal freedoms will be maintained.

This pessimism also colours their impression of the city’s business prospects. Half (52%) of Hong Kongers say they are “somewhat” or “very” unconfident about Hong Kong’s economic prospects, and another 22% say they are “half-half.” Only 24% are sure the economy is heading the right way.

Businesses such as the city’s largest bank, HSBC, and its flagship airline, Cathay Pacific, have publicly affirmed their faith in the city’s economic and social future. But these corporate expressions of confidence belie private concerns. The strongest driver behind a wish to emigrate is a perceived loss of personal freedom (38%), with another 11% of Hong Kongers saying they’re most worried about the prospects of family members such as their children.

"A net brain-drain is underway, reducing demand for premises,” David Webb, the Hong Kong-based shareholder activist and founder of Webb-site.com, says. “I believe this is a combination of net departures of expatriates, and net emigration of Hong Kong people seeking a brighter, freer future, and foreign passports if they don't already have one.”

Whether emigration comes to fruition – people may cite daydreams when surveyed that they never execute – could determine drivers for residential real estate in particular. For now, property values are driven by expectations of interest rates and rentals, Webb notes. Although property markets take longer to adjust than the stock market, that is happening.

“Although record-low interest rates have supported valuations, the rate curve has now begun to rise while rentals have been falling,” Webb says. Hong Kong commercial rents have fallen for 21 months in a row. “Rentals are highly sensitive to occupancy rates, and hence highly sensitive to economic activity.”

A net brain-drain is underway, reducing demand for premises. It is a combination of net departures of expatriates, and net emigration of Hong Kong people seeking a brighter, freer future

Companies are certainly shedding space, although corporate motives may be harder to discern. The Singaporean bank, DBS, in mid-March reportedly surrendered two of the eight floors it occupies in the Swire Properties development One Island East. The bank’s Singapore management had already said it would offer employees bank-wide the flexibility to work remotely for as much as 40% of the time, as well as introducing a job-sharing scheme.

Société Générale in late March gave up one floor in another Swire development, Three Pacific Place, again citing out-of-office work as a factor. Most eye-catchingly, Standard Chartered is moving out of eight floors that it occupies in the Standard Chartered Bank Building in Central. On construction, the bank agreed to a leaseback deal with Hang Lung Properties, which developed the current skyscraper and is landlord to the bank in the building that carries its name.

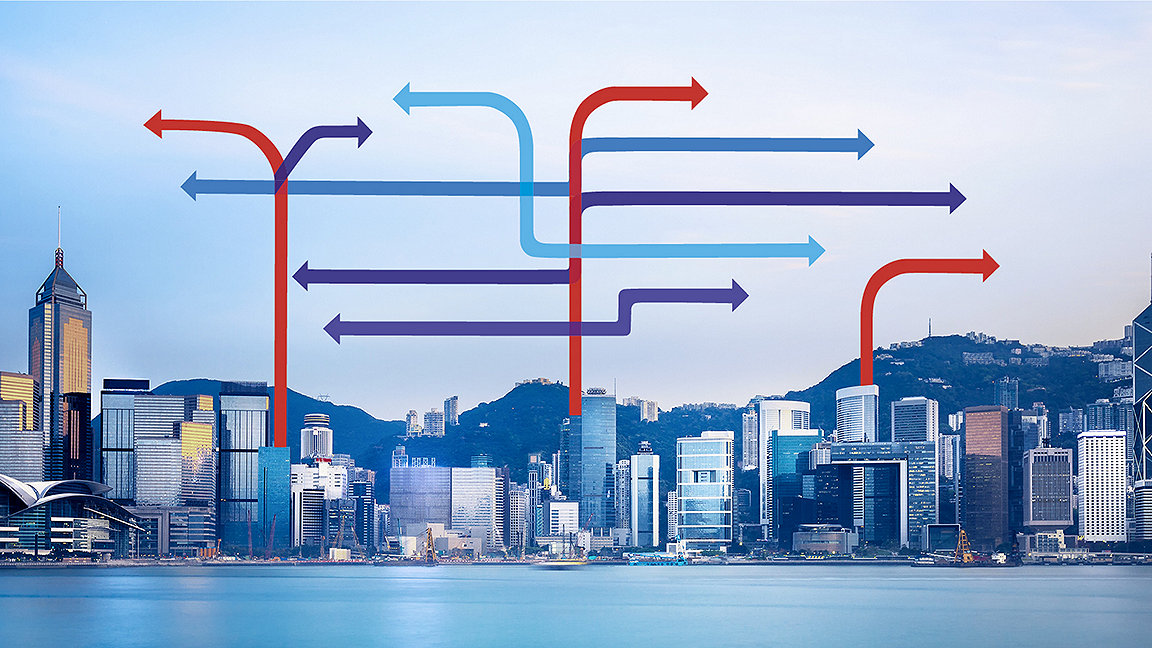

The tallest tower on Hong Kong island, Two International Finance Centre, is a microcosm of what’s happening citywide. In 2020, the European banks UBS and BNP Paribas cut back on the space they lease, together with Japanese investment bank, Nomura Holdings, and the US index provider State Street. Mainland Chinese companies have largely taken their place. The little-known Bank of Dongguan, for instance, moved into the 25th floor vacated by Nomura.

When the tower first opened in 2003, multinationals accounted for close to 70% of the tenants. But mainland Chinese tenants now account for 43% of the 81 occupants of the harbourfront tower, according to the Apple Daily newspaper. Hong Kong service providers have also beaten a retreat, their number dropping from 10 in 2003 to just three now, two of which – the MTR subway operator and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority – are government-backed. Henderson Land, one of the city’s largest developer, also remains.

Commercial property, its appeal already dented by the pandemic, stands to take the most-direct hit. Commercial brokerages and property professionals will also face a drag if the multinational companies they typically represent depart, a void they need to fill with mainland Chinese clients.

“The demand for offices has been dampened by concerns from foreign businesses and investors over the medium- to long-term outlook for Hong Kong,” admits Tommy Wu, the lead economist in the Hong Kong office of Oxford Economics. “While the number of regional headquarters in Hong Kong didn’t change much in the past two years, some companies had moved key personnel out of Hong Kong – but this could be due to downsizing of the Hong Kong offices as a result of heightened political uncertainty or because of the pandemic.”

Asian capital and gateway cities such as Singapore and Tokyo stand to gain. While some companies make flashy announcements about their choice of Asian headquarters, the changes may not always be headline-grabbing if a company decides to shift headcount gradually away from Hong Kong to another Asia base.

Companies in particularly at-risk industries such as the media may uproot altogether. The New York Times relocated its Asia news hub from Hong Kong to Seoul, expressly because “China has stepped up its efforts to impede the affairs of the Asian metropolis”. Its digital newsroom takes over 24/7 coverage during the Asian day from the newspaper’s other two global headquarters in New York and London.

The decision in July 2020 to move that editorial base to South Korea came after the June passage of the National Security Law in Hong Kong. Employees of the newspaper have also struggled with work permits, as Hong Kong immigration authorities, for instance, refused to renew the work visa of veteran China correspondent Chris Buckley.

Such censorship by work permit is a common problem in mainland China that had not previously been an issue in Hong Kong. In March 2020, the Beijing authorities expelled multiple journalists working for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post from mainland China after the Trump administration said it would treat five state-owned Chinese news organizations including the official wire service, Xinhua, as government entities.

Any restriction of work permits for professionals in Hong Kong would further diminish Hong Kong’s status. “Other regional centres will benefit from a shift in multinational activity,” Webb says.

Hong Kong had claimed for 19 years the title of the world’s freest economy in rankings compiled by the Heritage Foundation, only for Singapore to supplant it in 2020. This year, the foundation ditched Hong Kong from the ranking altogether, since “developments in recent years have demonstrated unambiguously that those policies are ultimately controlled from Beijing”.

It will be hard to discern whether waning office demand in Hong Kong stems from the erosion of its position or trends to downsize offices, likely a combination of both. Wu notes that this drag on demand is exacerbated by the impact of “work from home,” which he believes “will likely persist” as a permanent option for many companies.

For residential, purchasing and price pessimism started before the political turmoil, when Hong Kong’s economy began sliding in 2018. While transactions in the Hong Kong property market froze temporarily during the 2019 protests, when it became hard to move around the city, “the political events didn’t seem to have much impact on the housing market,” Wu insists. “However, the demand for housing should be weaker for housing units gearing towards expats.”

The number of property transactions in Hong Kong, of all kinds, has been on a persistent slide since 2017. Last year’s tally of 75,781 sales & purchase agreements signed was down 12.5% from the level four years ago. It is a far cry from the 118,011 deals struck in 2012.

Residential deals were very slow at the start of 2020, when protests led into COVID-19. They appear set to make up for lost ground in 2021, judging by a strong first quarter. Home prices have fallen 4.9% since May 2019. But they look to be turning, with Cushman & Wakefield anticipating an increase of 5% in Q2 2021, compared with the same quarter last year. Holding them back is the high and still rising jobless rate in Hong Kong, at 7.2% as of February 2021. The import and export sector has been hard hit, alongside the retail and food sectors hit hardest by the pandemic. Like office vacancies, the jobless rate is now at its highest level since 2004.

A sustained outflow of Hong Kong households to countries such as the United Kingdom would surely drain some demand from the market. Britain has estimated that 322,000 Hong Kongers may emigrate from Hong Kong over the next five years, resulting in a “net benefit” of £2.9 billion (US$3.7 billion). The numbers could be much higher as about 3 million citizens qualify under a new visa scheme launched in January that allows five-year residence with the chance to work, followed by a year of permanent residence and, ultimately, citizenship.

The future of Hong Kong’s property market both at a commercial level and on the residential scale will reflect whether plans turn into action. The prospects of the property profession in the city will surely follow suit.