Hong Kong skyline

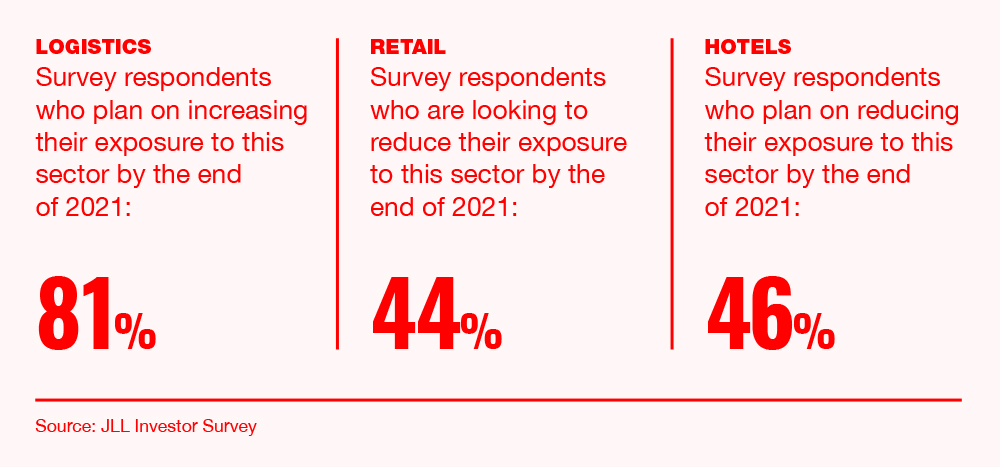

In the Asia Pacific region, the strongest property sectors coming out of COVID-19 (even before we come out, in fact) are the logistics industry and data centres. Delivery and data have been the essential backbones of our newly confined world.

Lockdowns and work-from-home arrangements have “fundamentally changed the way people shop and work, trends that are likely to continue”, says Denis Ma MRICS, a partner at Hong Kong-based wealth-management company Generations.

Retail space, considering the shift to online commerce, was already given a wide berth by many property investors even before the coronavirus. Mall closures and social distancing only made operations tougher during the pandemic, and there isn’t a clear way back.

Local last-mile heroes

Unexpectedly, Ma, who previously headed Hong Kong research for JLL, sees a future for “select retail assets” in the suburbs of large cities. These may benefit from the same kind of geographic dispersal that is likely to occur with office space, when companies deploy a decentralised hub-and-spoke system of satellite offices and scale down the expensive headquarters downtown.

Suburban retail operations could succeed if they are able to morph to accommodate third-party logistics fulfillment. They may also benefit from the shift from e-commerce to q-commerce (quick-commerce) whereby small amounts of goods are dispatched over short distances in record time.

Last-mile logistics have been a problem for large merchants and distributors. If the local mall becomes your last-mile delivery dispatch or click-and-collect pickup point, it stands to gain a new revenue stream, as well as frequent footfall.

Retail’s problems pre-date the COVID-19 crisis, but the poor economic environment is heightening tensions between store operators and the owners of the retail space. There have been some subsidies offered to retailers in Asia, but they have done little to plug the hole in their profit-and-loss statements caused by the lack of business. Retailers that were already heading out of business have been pushed faster that way.

“For retail, COVID-19 has really just exacerbated the structural changes that were occurring in the sector,” Ma says. “While we continue to see reasonable interest and demand on the leasing side, there remains a substantial expectation gap in rentals between landlords and prospective tenants.”

“For retail, COVID-19 has really just exacerbated the structural changes that were occurring in the sector” Denis Ma, Generations

Rises and falls of residential

Residential property has been another problematic area for institutional investors, mainly because it is “bitty” and difficult to invest in at scale. Adding to that, valuations have been pushed near record highs in the most popular cities in Asia-Pacific by persistently low interest rates, which have encouraged buyers.

Ma says Generations is “relatively optimistic” about multifamily apartment assets and co-living operations in larger cities. People who previously might have been trying to step onto the property ladder may have been blocked by the COVID-19 crisis and resultant recession. To make matters worse, access to capital is cheap, meaning landlords can expand portfolios.

“Demand for rental properties will be supported by a more fluid workforce and poor housing affordability, ironically because of a sustained low-interest-rate environment,” Ma explains. But he is cautious about the housing market in general, saying: “Elevated housing prices and significant levels of household debt are likely to curtail any upside in housing prices over the short-term.”

The end of the vanity office

Meanwhile, flagship offices in city centres are losing their lustre. Such properties with strong rental covenants had been the preferred destination for a lot of capital from institutions such as pension funds and insurers. The investors often viewed their holdings as something akin to a bond in terms of assured long-term rental cashflow.

That position is now at risk. The success of work-from-home policies in many companies has encouraged executives to consider ditching their vanity corner offices. Companies such as Twitter and Google have declared that all employees can work from home.

While this wouldn’t work for all companies, many larger businesses may convert to a “hotel” style of office, which people visit when they want or need to access to colleagues and facilities. Cutting two days of office per employee per week cuts 40% of traditional work-week office demand.

Slow recovery for hotels

Actual hotels – rather than your “o-tel” part-time office – are likely to be the last sector in Asia to recover from COVID-19. It is unclear how long the massive disruption in business and leisure travel will last. Even when those trips become possible, they may be less common, and require greater distancing by the hospitality sector.

It will bring the world full circle if China, the place where the COVID-19 crisis began, ended up as the saviour of the hotel and travel industry. As the world’s biggest source of tourists pre-crisis, the Middle Kingdom is also one of the first nations to allow a return to country-wide and international travel.

“Early indications suggest that domestic tourism in China has picked up since travel restrictions were eased,” Ma says. “If this translates into the outbound market, then markets that are reliant on Chinese outbound tourists, such as Hong Kong, Macau, Philippines, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam and South Korea would stand to benefit.”