Walk around any big city and you will see an urban landscape shaped by disease. The cholera and yellow fever epidemics in Europe and the US spurred the movement for efficient wastewater infrastructure, which in turn shaped the size and orientation of streets. Parks such as New York’s Central Park and Boston’s Emerald Necklace were created to purify the air and for people to escape unhealthy neighbourhoods in the 1800s and 1900s. The flat roofs, terraces and balconies of modernist architecture owe much to the design of sanitoria, which began in the mid-19th century as a cure for tuberculosis.

“After vaccines became more widely used, the impetus to more closely tie the built environment to health became less urgent, but it is no less important [today],” says Sara Jensen Carr, architecture professor at Northeastern University in Boston and author of The Topography of Wellness: Health and the American Urban Landscape. “The built environment can be both highly supportive to health outcomes or detrimental to disease, especially as it is inequitably distributed,” she says.

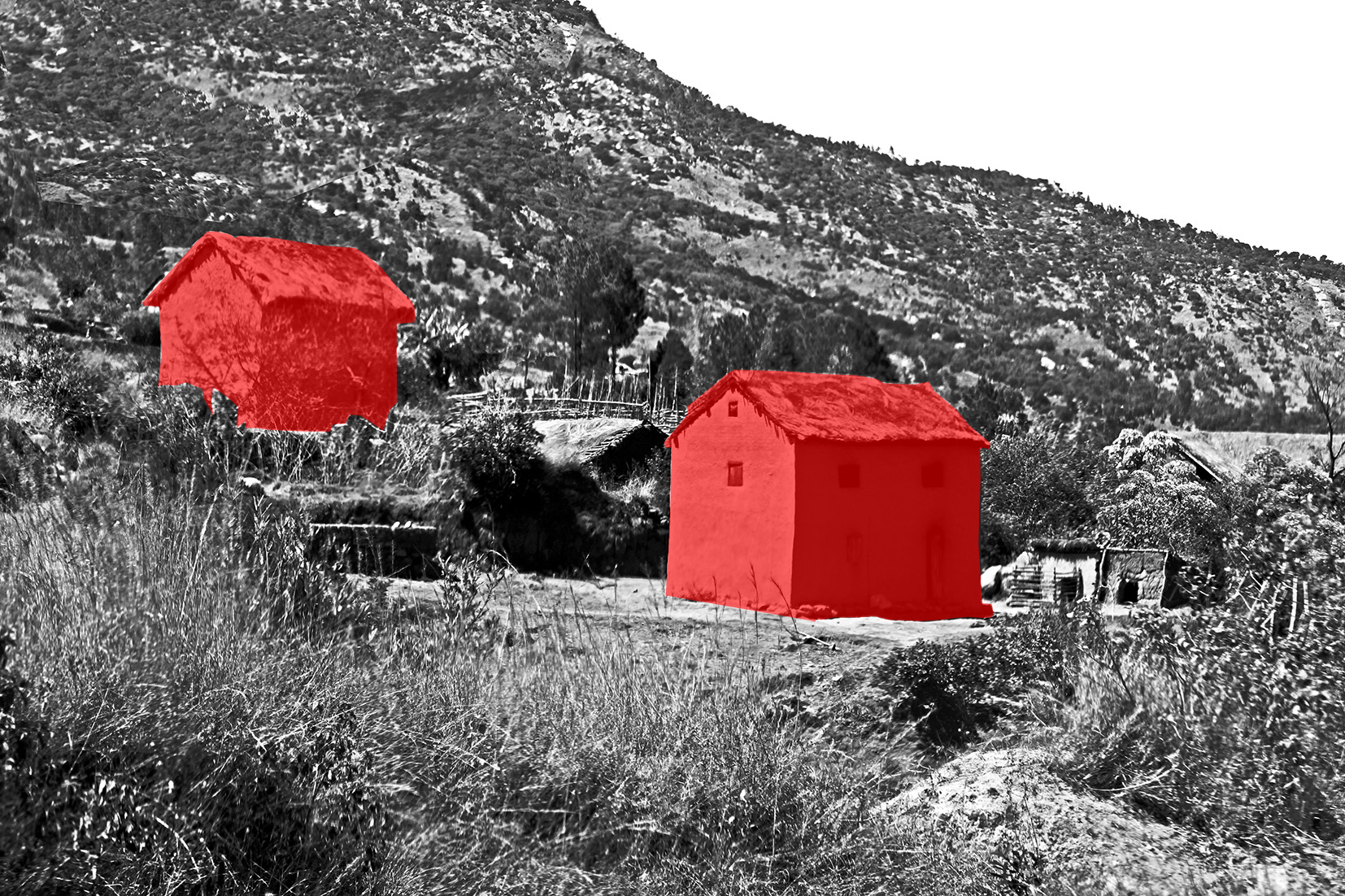

Consider insect- or vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue or zika, which today account for more than 17% of all infectious diseases worldwide. Malaria alone kills more than 400,000 people every year and in sub-Saharan Africa, 80% of transmission by Anopheles mosquitoes (the only genus that carries malaria) occurs at night in the home. A project led by Steve Lindsay, professor of public health entomology at Durham University, has shown that by applying claddings such as bamboo, shade net and timber, and elevating houses by up to 3m, you can reduce the infection rate by 80%.

“The smell of people attracts mosquitoes, so we’re now doing computational modelling of air movement in African houses,” says Lindsay. “If we can understand how that air flow gets out, we can understand how the mosquitoes get in.”

These are simple adaptations with big net effects, so why aren’t they already being scaled up? Part of the reason is that epidemiologists today have little interaction with engineers and urban planners. Lindsay hopes coronavirus will change that. While diseases such as Covid-19 come from all over, and cross over to humans from all sorts of animals, if there’s one commonality, he says, it’s stressed landscapes. These are often characterised by aggressive conversion of wild land for farming, logging and mining, which force species to change their habitats.

Overcrowded informal settlements, typically lacking basic sanitary or healthcare infrastructure, can also be hotbeds for transmission. In Africa, for example, while good-quality housing has improved over the past 15 years, the proportion of the population in informal settlements remains stubbornly at 45%.

"Disease spills over from the poor to the rich and the poor bear the impact"

In the face of rapid urbanisation and population growth, and when you can travel anywhere in the world in 48 hours, future epidemics are likely to occur more often than they do now, says Lindsay. The question is what we do to reduce the threat. “The coronavirus illustrates how diseases spill over from the poor to the rich, and the poor bear the impact. We’ve got to rebalance the focus from tertiary medicine to prevention, which is public health, and we’ve got to get engineers and city planners to make decisions about health together.”

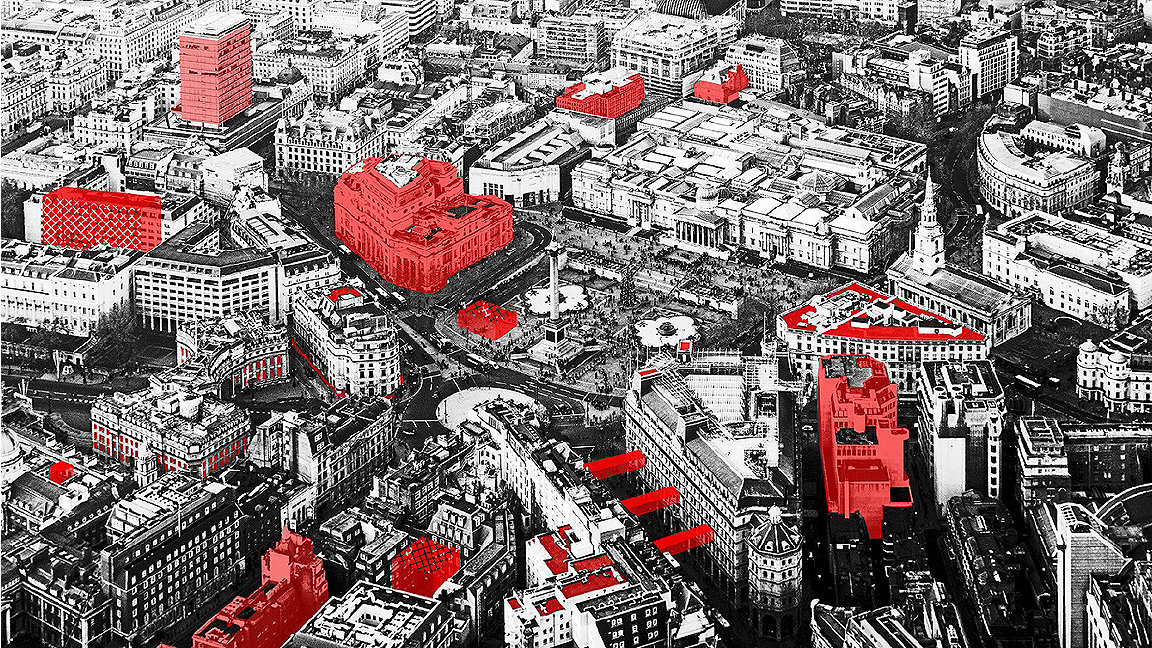

As countries around the world begin to get people back to work and reopen their economies, they will need to address this challenge. Research group _Streets at the University of Central London’s Bartlett School of Architecture, for example, found that only 36% of London’s pavements were wide enough for people to observe the government’s advice on social distancing, meaning that in most of the city, people would need to walk in the road to pass each other.

Effectively addressing the demands of social distancing will require reallocating street space: pavement widening, car-free zones and cycleways. It will mean brightly coloured markings on train platforms to indicate where to stand, and re-engineered passenger flows through stations. In Paris, mayor Anne Hidalgo has dubbed it “tactical urbanism” – the city and national government plan to spend €20m on a package to encourage cycling to reduce crowding on public transport, including 50km of temporary cycle lanes. Milan is aiming for 35km of cycleways; Brussels 40km. In New York, the city has closed 100 miles of streets to cars. Some of these measures will be temporary, others could alter the fabric of those cities forever.

Immediate measures, Jensen Carr says, are changes in the way we use public transport and buildings such as offices and schools. This correlates with what we know so far to be the most high-risk factor for virus transmission – internal population density. In other words, you are much more likely to catch or spread the virus in enclosed places where there is a high number of people per square metre of space, as this increases the chance of close contact and for droplets and aerosols to accumulate. This includes open-plan offices, churches, hospitals, trains, planes and cruise ships.

Elek Pafka, lecturer in urban planning at the University of Melbourne, wrote about this “micro-spatial logic” of coronavirus in a recent piece for The Conversation. Of 131 people whose infection centred around a high-rise office building in Seoul, 94 were in a crowded open-plan call centre on a single floor. Only three other people in the building were infected. The infected workers then spread the virus to 34 family members in their homes across the city.

Addressing this challenge in the short term will be shaped by a combination of policy and behavioural change. Convincing people that public transport is safe to use again will mean running it more frequently to avoid crowding and diverting some of that capacity to walking and cycling. Even then, the sudden transition to working from home is likely to stick, but by how much is likely to vary by sector, company and working culture. Companies will have to stagger occupancy to allow for more distancing. Some may decide to give up workplaces altogether. Schools will likely look at more long-lasting infrastructural changes to facilitate social distancing and sanitising. On a micro level, ventilation and conditioning systems will be scrutinised, and contactless technology will be installed in doors, elevators and bathrooms.

Health checks

Duncan White, global industry and science lead at Arup, says we should also expect more monitoring of our health. This includes people having their temperatures taken as they come into buildings, as well as through government-backed track-and-trace apps. Arup is using its pedestrian modelling software, MassMotion, to help airports and railway stations estimate safe capacities. Sensors will become more prevalent, and there’s likely to be an increased alignment of the data sets used to monitor people, which will be a challenge for data privacy.

Nicola Gillen, head of total workplace, EMEA, at Cushman & Wakefield, says that clients are starting to think longer term but are wary of how much physical investment to make in a climate that is going to change.

Cushman has already helped a million people return to the office in Asia, using a three-step process (see opposite). The first step looks at who needs to come to the office and why, the second looks at people’s commute. Third is understanding the volume of people who need to return. “For some clients the answer is none. Others are looking at percentages. Nobody is looking at 100%.” It’s only once this percentage is understood that it’s time to start looking at buildings. Most companies are bound by leases. Occupancy data for leased offices before coronavirus was 56%,” says Gillen.

“It hasn’t made sense for some time to bring thousands of people together in cities to work alone. Now, when we overlay the difficulty of social distancing and the implications of climate change, there will be more of a fundamental question about what can be done remotely and what is the best way to spend time on [face-to-face communication] – and it will be training, social events, and certain parts of the creative process. This doesn’t necessarily mean less office space, but it will be used in different ways.”

Claims that urbanisation might go into reverse is something of a “rabbit-in-the-headlights moment”, according to Jeremy Kelly, lead director of global research at JLL. “Even before the pandemic there was a narrative that smaller cities ‘will have their day’ and to a degree Covid-19 is helping that argument. It could encourage a more distributed urbanisation – not necessarily suburbanisation, but a polycentric structure – but we’re not predicting any fundamental decline in cities.”

Some of this redistribution could be supported by government stimulus funding, says White. For example, as the UK government looks to exert greater control over critical supply chains through onshoring manufacturing, warehousing and bio-pharmaceutical facilities, there is an opportunity for those investments to be mapped so that they go where they’re needed socio-economically. To support these supply chains, White predicts a surge in the need for cold storage and warehouse facilities, of which there is a shortage in the UK, to be delivered through rapid modular construction.

Space is already being repurposed on local high streets, which have been affected all over the world by enforced store closures. “The high street’s future doesn’t lie in retail,” says architect Jan Kattein, whose London-based practice specialises in high-street regeneration projects. “One of the most significant studies [for high streets] is the trend toward the experience economy. The crisis will lead to rediscovering the high street as a civic space – of work, learning, culture and community.”

It will also have a significant impact on the brief for public realm designers, he says. Alongside research by groups such as _Streets is a study by Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in Germany, which identifies a strong correlation between high levels of air pollution and deaths from Covid-19. It’s yet another argument for high streets being places rather than thoroughfares. And, as Jensen Carr says, “With any luck, cities will start to see the investment in public space as an investment in public health.”

The 21st century has so far seen SARS, MERS, Ebola, bird flu, swine flu and now Covid-19. While only a vaccine will cure the coronavirus, how we choose to adapt our cities is an opportunity to reduce the risk of the next one, and to start to see the built environment as a vector for positive health outcomes.

PANDEMIC PROOFING

1. Now safe for work

Cushman & Wakefield Netherlands has been collaborating with the Well Living Lab to pilot a design to help clients prepare for social distancing in the office.

In the “6 Feet Office”, signs direct people to walk around the space in a single clockwise direction. Floor markings tell people where to stand in elevators and when they’re in proximity to colleagues’ desks.

Everyone uses a paper desk pad, replaced each day, and screen protectors divide desks. The Well Living Lab will be collecting data from all participating sites to keep adapting the guidelines.

2. The plug-in hospital

To help healthcare providers respond to a potential second wave of Covid-19 cases, Arup has designed Carebox – a ready-to-use modular field hospital that will quickly ramp up critical care. The “plug-in” hospital provides access to medical gases and can be attached to existing hospital buildings. Two other specifications of Carebox enable new wards to be created in vacant commercial spaces, and for venues or temporary structures to be converted into hospitals. Arup hopes it will be effective in developing countries with limited healthcare infrastructure.

3. Reclaiming the streets

New South Wales in Australia is rolling out a state-wide programme to promote what it calls “temporary activation projects” to increase the amount of available public space. The Streets as Shared Spaces grant is designed to help local governments adapt streets, paths and local businesses to social distancing requirements. But the hope is the changes will stick. According to the NSW government, no project is too small and they can be a quick, low-cost method to demonstrate the value of a concept and test future permanent change.