It’s been five years since the early hours of 14 June 2017, when Grenfell Tower in west London suffered a catastrophic fire and 72 lives were lost.

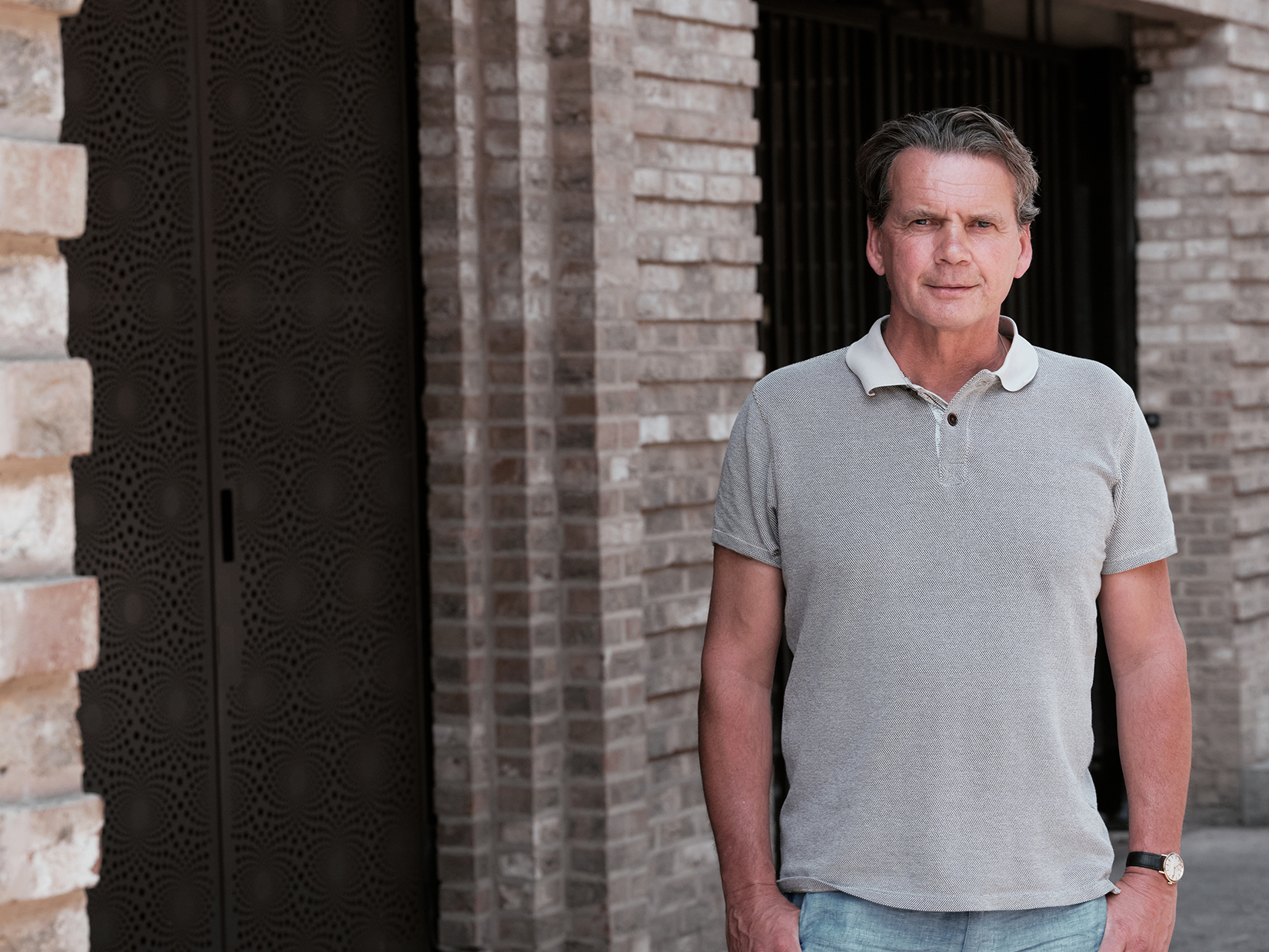

Ed Daffarn is a former resident of Grenfell Tower, who lived on the 16th floor. He is a member of Grenfell United and has been attending the Grenfell Tower public inquiry, which continues to examine the circumstances of that tragic night.

He spoke to Modus to explain how the fire exposed major shortcomings in the social housing sector, why he believes social housing tenants continue to be mistreated and what must change to prevent similar disasters occurring in the future.

Where are you today and what is happening there?

We’re now in the aftermath stage of the Grenfell Tower public inquiry. The inquiry is just focused on the seven days after the fire, but our ill treatment has been a lot more expansive than that. I’ve always thought of Grenfell as a tragedy in three acts – how we were treated before the fire, how we were treated on the night of the fire and how we were treated subsequently.

On the night it happened, we were left standing in the street and if it hadn’t been for the local community and local faith groups and youth centres opening up, we would have been standing there a long time. Being abandoned in the fifth richest country in the world in the 21st century, when we purport to be very different to that, was very painful and still hurts.

What was your experience of the fire in the early hours of 14 June 2017?

It was a really hot evening – I’d gone to bed and started listening to a radio show and that had kept me up a bit later. I was lying in bed awake around 1am and heard my neighbour’s smoke alarm going ‘ping ping ping’ through the wall. I didn’t even get out of bed, I just assumed my neighbour must have burned some food.

About five minutes later I heard some shouting in the communal area and that got me out of bed. I put on a pair of shorts and a t-shirt, went to my front door, opened it, and instead of seeing my neighbour out there like I expected, this black, acrid smoke was swirling around.

I closed the door straight away and my heart sank. I thought ‘this isn’t just my neighbour, we’ve got a proper fire going on here’. We’d been told by the TMO (tenant management organisation) that we should stay put if something like this happened. And that’s probably what I would have done if it hadn’t been for the fact my phone rang and it was a neighbour of mine from downstairs who just shouted at me ‘GET OUT, GET THE F*** OUT!’

It was something in the power of his voice and the way he told me that I didn’t say, ‘look, I’ve opened the door, seen a lot of smoke and I think I’ll stay here’, I just thought, I need to go. So I wrapped a wet towel around my mouth, went out into the hallway and closed the door behind me.

Then I had to walk between my front door and the emergency stairwell which was probably about 15-20 feet, not a great distance, but I couldn’t see anything because the smoke was so thick. Instead of finding the door to the stairwell, I found a wall. And I started panicking and pawing at the wall, so I dropped the towel and started inhaling the smoke. I was thinking ‘I’m going to die now’. At that moment, a firefighter had come through the door and was crawling along the ground where the smoke was thinner. He grabbed hold of my legs, stood up and pulled me out of there into the stairwell.

Once I got my breath back, I experienced what is called ‘fight or flight’ and just ran for my life down the building and got outside at about 1.30am, by which time the fire had been going for 40 minutes. It was the most horrific scene, the whole side of the building was ablaze, people were at the windows and it was really distressing.

The firefighters said it was a million to one shot they found me because they’d actually come to get my neighbour whose smoke alarm had gone off. Unfortunately, he died in the fire – we lost two people on my landing.

“I’ve always thought of Grenfell as a tragedy in three acts – how we were treated before the fire, how we were treated on the night of the fire and how we were treated subsequently” Ed Daffarn, Grenfell United

Is it still the case that official instructions are to stay inside during a fire, in buildings of that type?

Yes, even now the advice is still ‘stay put’, because compartmentalisation is meant to work. There were previous fires in towers where it was a concrete structure and didn’t spread, but in our case they used this cladding that was like petrol on the outside of the building and it wasn’t safe to stay in the building any more.

“I went to my front door, opened it, and instead of seeing my neighbour out there like I expected, this black, acrid smoke was swirling around” Ed Daffarn, Grenfell United

You were labelled ‘a troublemaker’ by the local authorities for raising concerns about fire safety in Grenfell Tower. Do you think landlords and TMOs are now paying more attention to residents on similar issues?

I would certainly hope so. Before Grenfell, the only way you could get your voice heard was to set up a blog and use modern social media methods like Twitter. One of the things we were most keen to change after the fire was that Twitter shouldn’t be the only way to get your voice heard by your landlords.

I’m not saying that I wasn’t a challenging individual for these people, but they needed challenging. They didn’t like being questioned. The KCTMO (Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation) spent a lot of time during this inquiry trying to drag my name through the mud. The truth of it is, that we stood up to people who wanted to have it all their own way.

Unfortunately, five years on, I think many social housing tenants would say that the system hasn’t changed significantly enough. The white paper on social housing is supposed to be the vehicle to bring meaningful change.

What issues did that night highlight with high-rise housing?

We sat down very early on with some civil servants from what was then the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. We basically tried to hold them to account to make sure our concerns were at least being considered and listened to. We started off with a list of eight themes and issues and in the end they were whittled down to four main issues: how complaints are handled; how the regulator operates; tenant voice and how tenants are listened to and their concerns addressed; and the fourth is professionalisation – very few of the housing staff had any professional housing qualifications at all.

When you’re a social housing manager and you’ve got 200 properties under your control, the fact that you have no qualifications is bit worrying. We were the victims of that and want to make sure it doesn’t happen to other people.

A member of our committee works in the city in banking and he was quite keen to see if we could get a senior management regime introduced, where you’re responsible for the people under you. That was introduced to banking after the 2008 financial crash. We tried to get that included but failed.

We were trying to get the regulator to split with the commercial arm, which looks at the finances of the housing associations and TMOs, and we failed with that as well. We were dealing with Robert Jenrick (then Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government). We had a good relationship with James Brokenshire, a less productive relationship with Jenrick and we’re just in the process now of seeing what Michael Gove will or will not do.

How might Grenfell change the future of social housing?

Part of the problem of social housing is the culture within that sector. We were not respected and not listened to. They wanted to label us as rebels and troublemakers but we weren’t and there were other people like us up and down the country who raised concerns about the environment they were living in, be it damp, a rundown residential amenity or repairs not happening. Instead of being respected and treated properly by the landlord, they target you and that’s so wrong.

By profession, I’m a social worker and that’s because I believe people need to be treated with respect. Injustice to individuals needs to be challenged. Here we have a great injustice being done against a whole cohort of residents. It was a really awful experience to be a victim of the KCTMO.

I readily acknowledge there is a small percentage of very good housing providers and a larger percentage of housing providers that do a so-so job. But unfortunately there is large percentage of housing providers down the bottom… I’ve said it many times about the KCTMO – it was a racket, they were a mini-mafia, a non-functioning organisation who didn’t care about their residents. They weren’t in it for their residents, they were in it for what they could get out of it.

If ever a housing association needed evidence that they needed to improve, Grenfell was it but the fact that we are having this conversation now means it hasn’t worked. We need a regulator that is capable of carrying out proactive, unannounced or very short notice visits to really get under the bonnet of what these organisations are doing. Looking at how they treat complaints, handle evictions, how they facilitate tenant voice.

I hesitate to say the Ofsted model but schools really fear their visits and they talk to the parents and it’s short notice. It’s got to be meaningful; we can’t allow the rogue landlords to game the system. What the KCTMO was good at was gaming the system and knowing how to deal with a weak regulator.

Would you include physical building inspections in that too, by someone independent who has a job similar to a surveyor?

My understanding is that some of that stuff is being dealt with in the Building Safety Bill. It’s not my area of expertise but I think there’s now a responsible person for buildings and an onus on housing associations to have a named individual to ensure that health and safety issues are addressed properly.

Grenfell Action Group wrote a blog that some people said prophesied the fire. But it wasn’t a prophecy because if your landlord is unable to meet even the most basic of their health and safety obligations, then you’re not a prophet to see there could be catastrophic consequences.

“I’m not saying that I wasn’t a challenging individual for these people, but they needed challenging” Ed Daffarn, Grenfell United

What do property developers need to do to improve safety standards in social housing?

What the Grenfell Tower inquiry has brought to light is the shocking failure of the construction and property development industry in addressing even basic health and safety issues. It seems that health and safety fell very far down the priorities of the architects, developers, local council and building controllers.

All these different contributors did not have safety as their focus. The architects wanted to make the building look nice and the local council focused on the colour of the cladding but no one was asking how we keep people safe. As Grenfell or Lakanal House show, if you don’t build a safe building it’s going to come and get you later.

Is it the case that there wasn’t a sprinkler system in Grenfell Tower?

There was never a working sprinkler system inside Grenfell. One of the things that was really upsetting in the immediate aftermath was the council did a bit of victim blaming and tried to suggest that we as residents had refused a sprinkler system because we thought it would take too long to install. We were never consulted about a sprinkler system. And the reason we were never asked about it is because we weren’t considered important or valuable enough to have that kind of precaution put into our home.

There was a fire-resistant cladding that was available but they went for the cheaper, non-fire resistant option. It's the commodification of the housing industry – if you get involved with housing you can make a lot of money out of it.

In a few generations’ time they’ll look back and the judgement on what we’ve done with housing will be withering – our lack of care about how we build, what our priorities are when we build and the long-term outcome of that.

“There’s a feeling that we were treated as second-class citizens because we lived in social housing” Ed Daffarn, Grenfell United

What outcomes are you hoping for from the Grenfell Tower inquiry?

At Grenfell United we have three very clear aims. One, that truth and accountability comes out of the public inquiry. Our second aim is justice, that people go to jail or are held accountable for what they did to us. And the third one is change – people shouldn’t be going to bed at night with the same cladding on their buildings that we had on Grenfell. Five years later that’s still happening.

For me it’s about returning some dignity and respect to people living in social housing, ensuring they are listened to when they raise concerns and are treated as proper human beings. There’s a feeling that we were treated as second-class citizens because we lived in social housing. That really needs to change.

The Beveridge Report and the vision for the UK of delivering free healthcare, education and housing was what we demanded as a country after the Second World War. Social housing pays for itself, people who live there pay their rent, it’s self-sustaining. It’s a brilliant concept, on a level with the NHS or free education. But it’s come to be seen as something very different.

After the fire, some of the press ran stories that spoke of illegal immigrants, ‘spongers’ and sub-letting. The truth is we were articulate, hard-working, intelligent and community-minded people from broad ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds. We had a banker living in the tower, we had social workers, teachers, all kinds of different people. And we had some vulnerable people who weren’t able to work, with severe and enduring mental health issues.

It was painful that after the fire we were portrayed in that way – maybe that’s a hint as to why people who live in social housing are treated the way they are; people view them through the negative stereotypes seen in the media.

We came together because we were being treated very badly. I’m proud of the community we had beforehand and one of the great shames of the Grenfell fire is that we don’t have that community anymore.