Illustrations by Jack Taylor

The American dream to own one’s home has circulated far and wide, from Australia to Canada and China. While the saying goes that an Englishman’s home is his castle, it’s not so much the German dream and Romanians don’t see what all the fuss is about.

Members of the millennial generation, those born between 1981 and 1996, are now in their prime homebuying years. For those living in countries that prize homeownership – and reward it handsomely with tax benefits – the elusive quest to buy a home seems increasingly out of reach without outside help as home price increases have outpaced wages for several years. And in what has proven to be a topsy-turvy housing market after two years of intense house price appreciation, getting a foot on the property ladder does not look like it will become easier anytime soon.

Among countries where property ownership remains an imperative, perhaps nowhere do millennials have it worse than Australia. “Homeownership is an entrenched ideology and it’s really difficult for the younger generation to get a bite,” says Braam Lowies MRICS, senior lecturer in property at the University of South Australia.

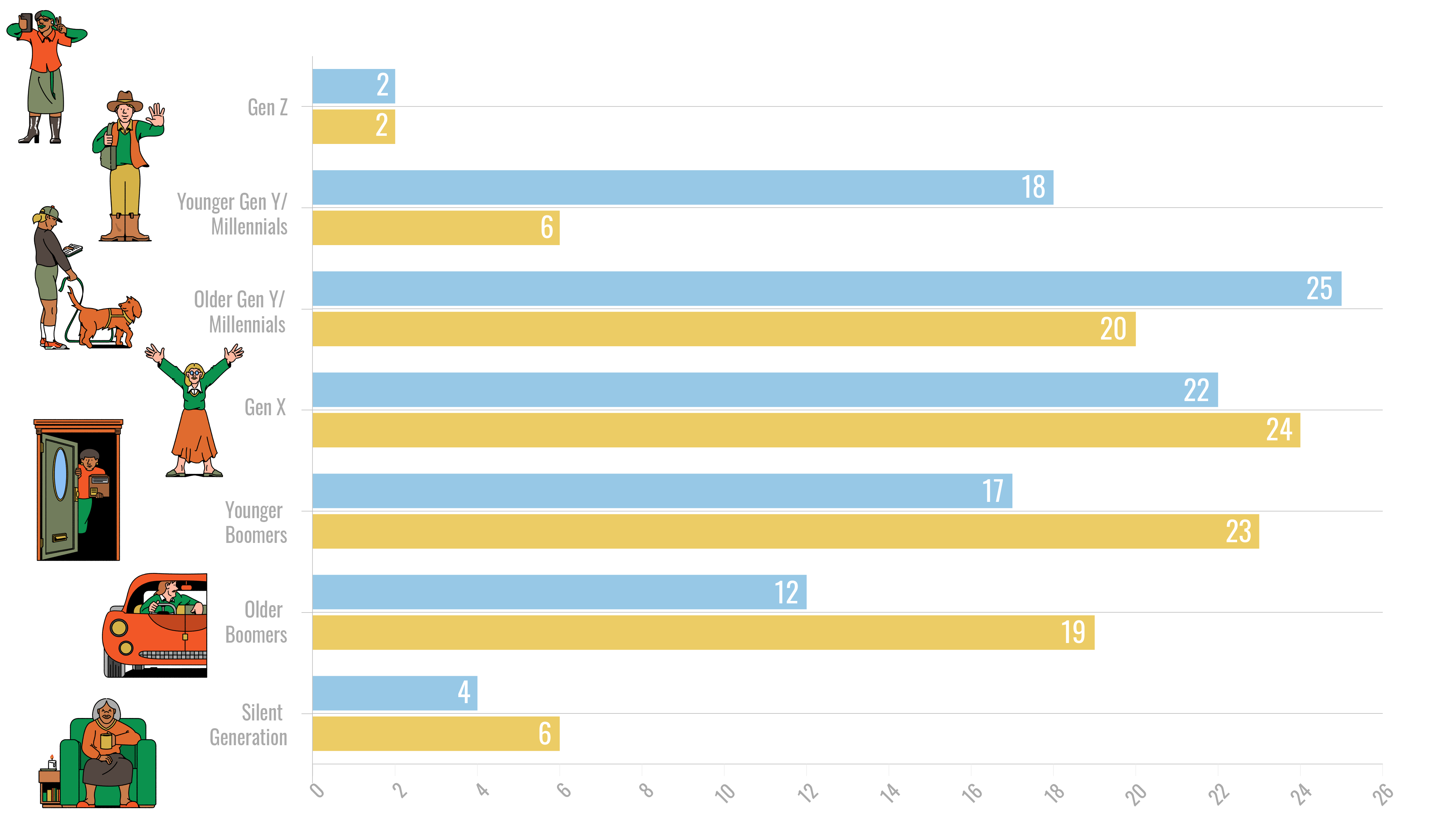

Share of buyers (blue) and sellers (yellow) by generation, %

In the United States, 2022

Source: 2022 NAR Home Buyers and Sellers Generational Trends

The generations relating to this graph are defined by their year of birth:

- Gen Z - 1999-2011

- Younger Gen Y / millennials - 1990-1998

- Older Gen Y / millennials - 1980-1989

- Gen X - 1965-1979

- Younger boomers - 1955-1964

- Older boomers - 1946-1954

- Silent generation - 1925-1945

Lowies is the co-author of a February report, “Not living the dream,” about the dire straits facing the country’s first-time homebuyers. The report notes that 73% of Australians over the age of 65 own their homes, while the government is encouraging them to age in place with home care and home support packages. Of those Baby Boomers, some 68% were already homeowners by the time they were 30-34, while just half of millennials have reached that milestone by the same age.

When a property does come on the market, meanwhile, it’s liable to be snapped up by an older investor rather than a younger family starting out. “That’s housing policy in this country,” Lowies says. “If you don’t have a second property, you’re certainly thinking of it if you have the means, because that will make your retirement even better.”

Earlier this year, Australia crossed the AUS$1m threshold for median house price, making it among the most expensive markets to buy property in those countries where homeownerships is highly valued.

Globally, house prices levelled out by September and are even beginning to decline in some markets, as central banks raise interest rates. But there are not yet indications of major dips in house prices coupled with sufficient wage increases to make housing broadly more affordable.

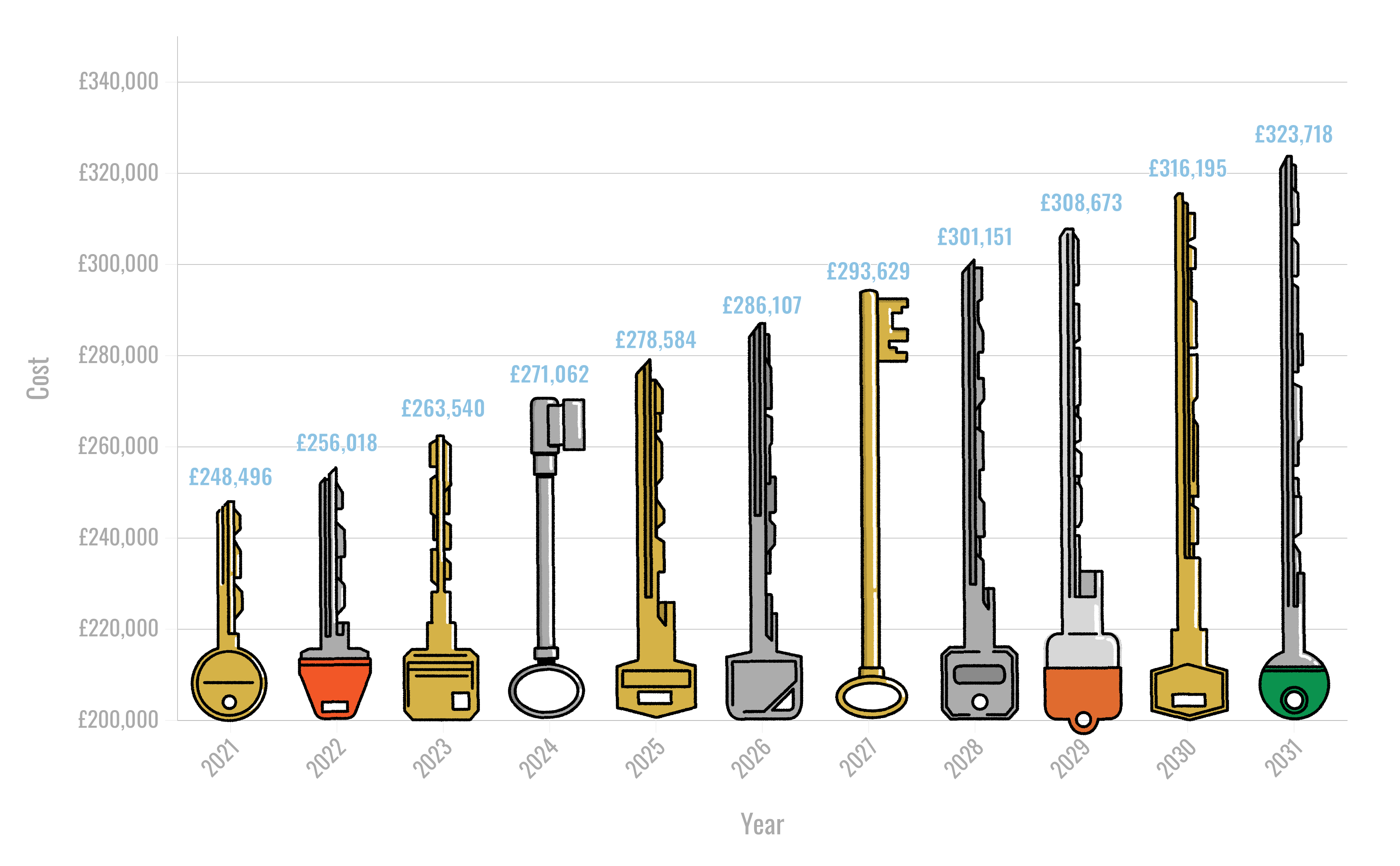

What will the average cost of a first house in the UK be in the next decade?

Source: Compare the market

A foot on the property ladder

Across the Pacific, Canadian millennials are likewise struggling, depending on their financial situation and timing. “The Bank of Mum and Dad was able to help a number of earlier millennials take advantage of the best pricing and interest rates in years,” says Sheila Botting FRICS, president of Americas Professional Services at Avison Young in Toronto. “The second and third waves behind them didn’t have jobs that paid them enough, or they held too much student debt. Whether you loaned them money or offered low interest rates, they couldn’t get a foot in the door.”

That distinction likewise exists in China, which despite a vastly different trajectory from housing markets like Australia and Canada has ended up in a similar situation. While China urbanised rapidly and built extensively to lift the country out of poverty, today’s Chinese millennials are facing similar challenges. “There is a big divide between those whose families bought property early on and can help with intergenerational transfers to pay for a down payment and those that don’t have that intergenerational wealth to fall back on,” says University of British Columbia professor Julia Harten, who studies Chinese housing markets. The Chinese term fangnu, loosely translated as ‘mortage slaves,’ describes a generation of urban property owners struggling under high debt-to-income ratios.

By August 2022, however, prices had dropped for 12 consecutive months as China’s red-hot property market shows signs of a bursting bubble and some high-profile developers are defaulting on loan obligations. While economists discuss the risk of a 2008-style subprime meltdown in China, other countries have tightened lending standards to avoid a repeat of the global financial crisis. The US Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, while the UK regulator adopted the MCOB (Mortgage Conduct of Business) rules requiring much higher loan-to-value mortgages, increasing required down payments, and requiring stress tests on borrowers’ income.

“It made the hurdle much higher [for millennials], but once they got in, then homeowners were paying less than tenants,” says London School of Economics policy fellow Kath Scanlon.

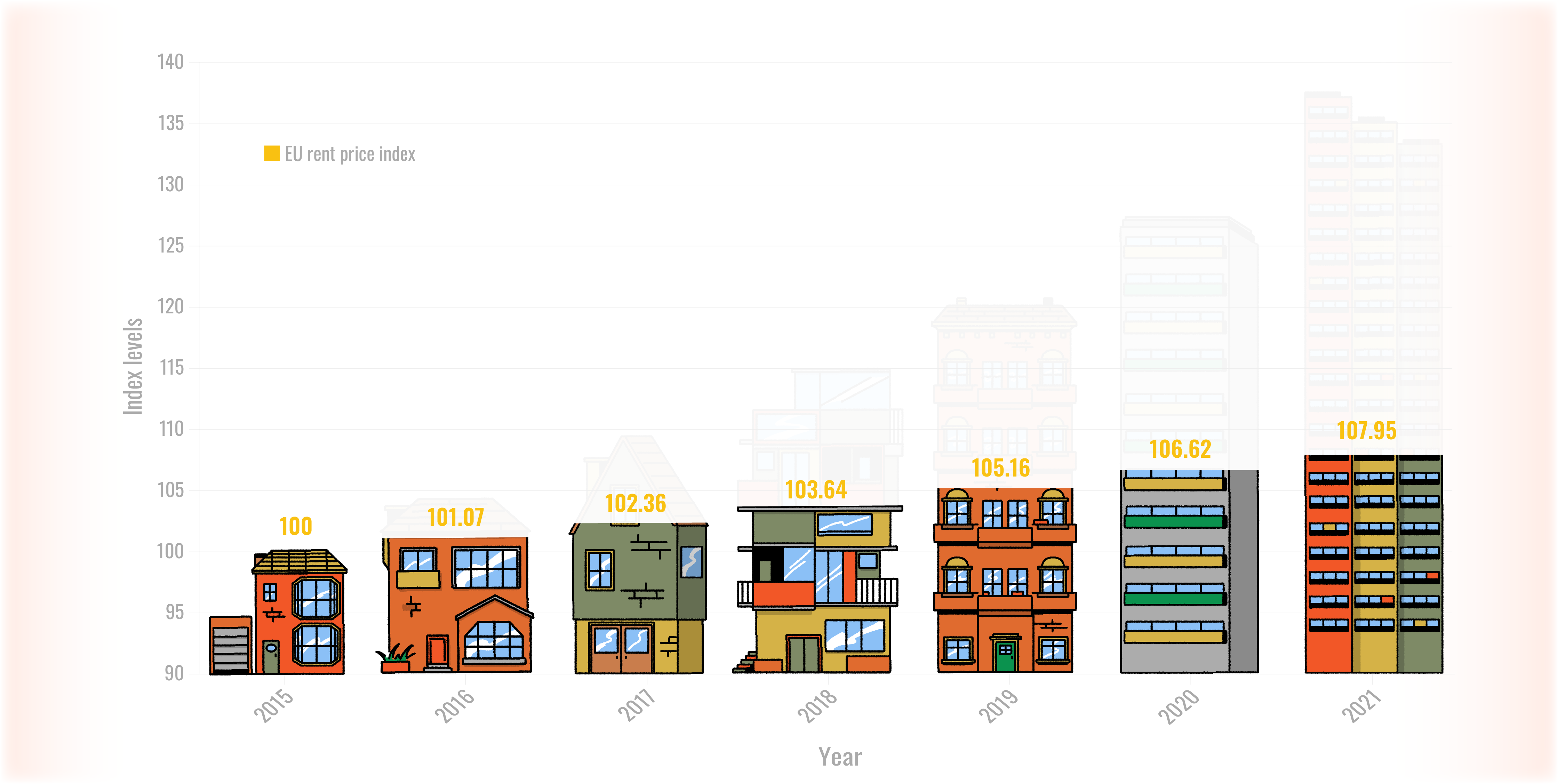

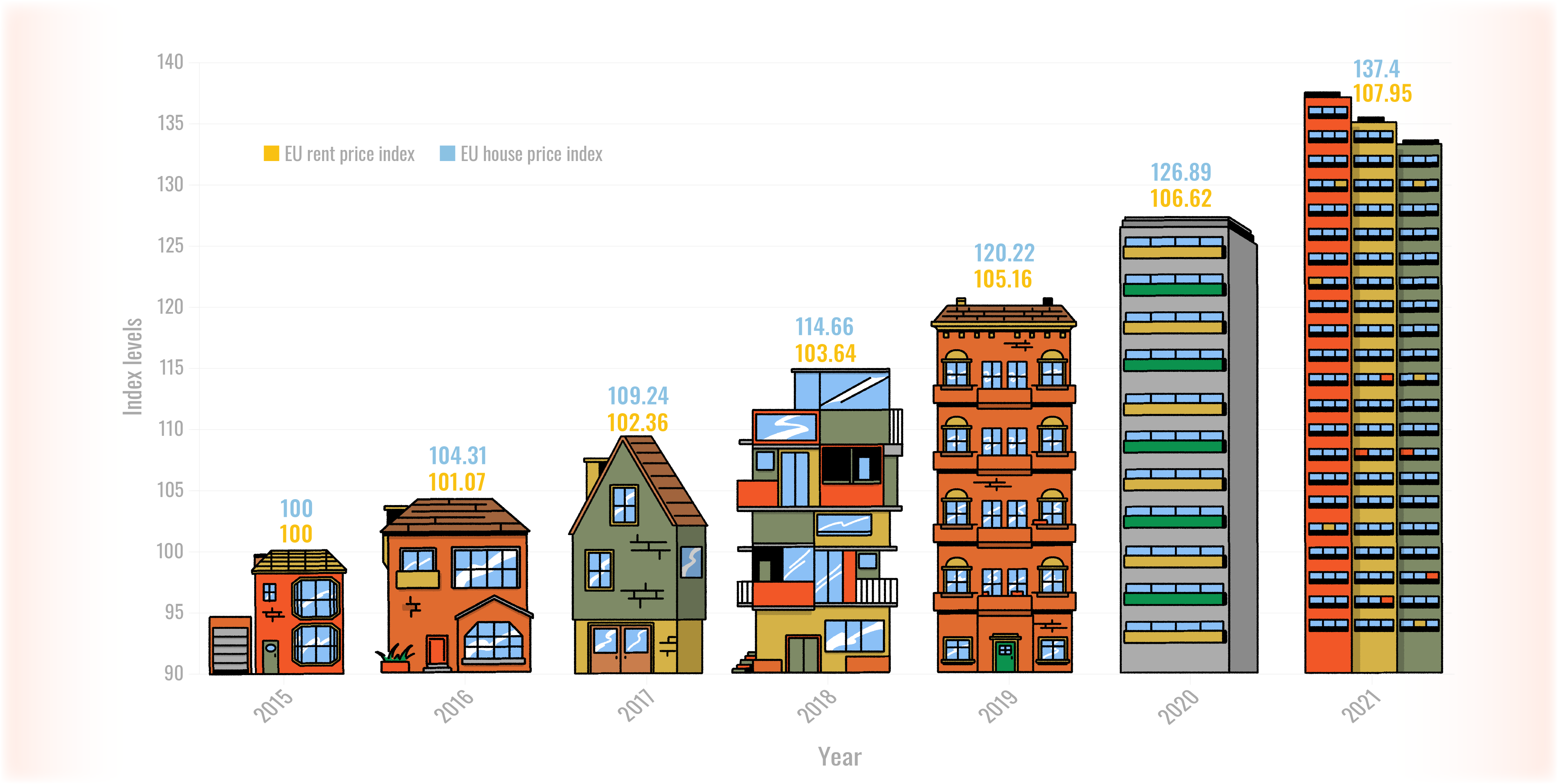

House prices and rents in the EU, 2015 - 2021

Click through to see the increase of house prices compared to rent, indexed to 2015

Source: Eurostat

Government help

What are governments doing to help millennials get over the hump? First-time homebuyers in England and Northern Ireland looking to escape so-called ‘Generation Rent’ benefit from a Stamp Duty exemption on the first £300,000 of property. Britons aged 18-39 can put £4,000 a year into a tax-free Lifetime Individual Savings Account, with the government adding a 25% bonus, which can be withdrawn to buy their first property.

Most Australian states offer a AU$10,000-15,000 first-time homebuyer grant – Tasmania’s is AU$30,000 – a concept that the Biden administration is now pushing in the US. In France, where the national homeownership rate is 64%, a number of housing policies can potentially benefit first-time millennial buyers. The prêt à taux zero loan offers zero down payment mortgages with a government-backed credit system to avoid making risky loans.

Those demand-side responses are only part of the equation, as house supply is another factor locking millennials out of the property market. New starts on Australian housing projects fell in the March quarter, though they rose slightly in the UK. Supply chain issues continue to hamper the construction sector, while some governments work to find more sites for development.

Toronto, the epicentre of one of North America’s most booming property markets, launched a Housing Now programme with well over 10,000 units, many affordable, in the pipeline. Ontario’s More Homes for Everyone programme is already bearing fruit: 2021 saw the highest level of new housing starts in over 30 years. The US states of California and Oregon recently eliminated single-family zoning, allowing at least two units on any previously single-family lot.

Pre-pandemic, nearly a third of 20-34 year olds were living at home with their parents, a 46% rise since 1999

UK average house prices and weekly earnings

(12-month rolling average), indexed to Jan 1970

Source: New Statesman

Stronger rights for renters

The urgency to build more for-sale housing for first-time millennial buyers – and soon their younger Gen Z counterparts – is not universal. German housing policy, for example, does not tilt the playing field in favour of owners, who are less than half the population. “The bundle of services that you get as a renter is much more like homeownership in many other countries – indefinite tenure, the right to pass on your lease when you die, the ability to make renovations,” says Scanlon. “Until recently, real house prices didn’t increase. If you rented, you weren’t foregoing capital appreciation.”

For former Eastern Bloc countries, where state-owned housing was sold off cheaply, or even given, to tenants, homeownership rates are among the highest in the world: 96% in Romania, 92% in Hungary, and 90% in Lithuania and Croatia. Millennials in Southern Europe, meanwhile, are bound by different cultural norms: They typically don’t move out of their parents’ home until they are married, which creates less pressure for young, childless people to buy property earlier in their careers.

“Everybody subconsciously thinks their home country is the norm and everywhere else is some interesting aberration. Homeownership rates in the UK fell from an all-time high of 70% in 2003 to 64% in 2018 and that is seen as alarming, but they are quite high by German standards,” says Scanlon. “The better question is: Do people have a meaningful choice about what tenure they are in?”