Photography by Ellis Vener, archive images from Getty

Montgomery, Alabama is a veritable open-air history museum – from the era of chattel slavery to the US Civil War and post-war Reconstruction period, to the Jim Crow era and Civil Rights Movement.

Above all, its historical sites shine as exemplars of effective nonviolent resistance to injustice and inequality. At the same time, African Americans suffered violence that was commonplace during decades of oppression and throughout their struggle for freedom.

In January, we profiled Warren Adams MRICS, the City of Montgomery’s land use control administrator. He is a Scotsman who is immensely proud to be part of the preservation of this historic state capital in the American South.

Following on from that profile, here are four noteworthy sites in Montgomery – with Adams explaining the distinct heritage preservation challenges each faces.

Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church 454 Dexter Ave. Montgomery, AL 36104

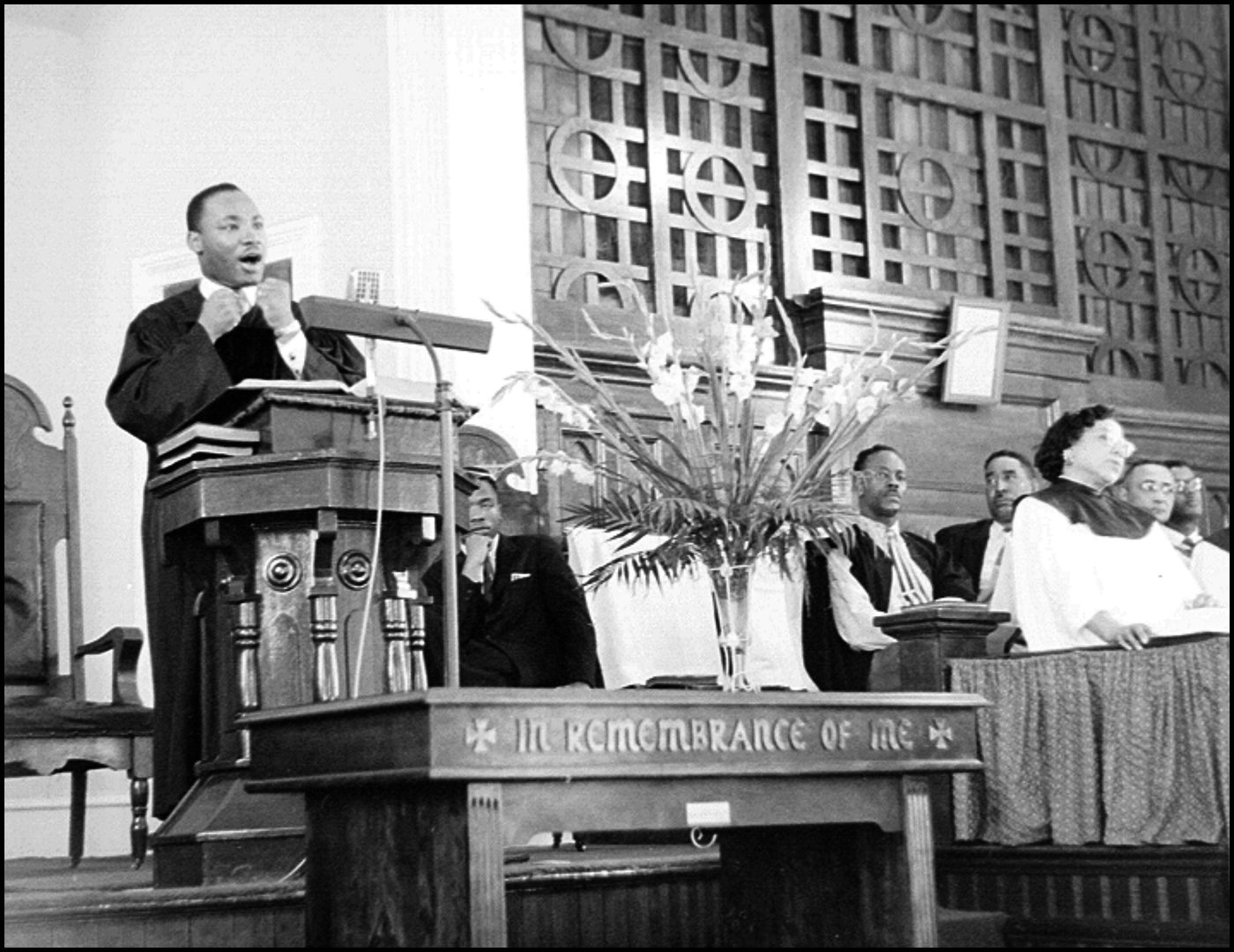

Freed slaves founded a Baptist church in 1877 and later purchased a lot on Dexter Avenue. The Gothic Revival red brick church was completed in 1889. In 1954, a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr took the pulpit, the only congregation King led by himself in his career.

In December 1955, Montgomery was thrust into the national spotlight when Rosa Parks was arrested after refusing to give up her seat in the ‘coloured section’ of a bus (in accordance with Jim Crow segregation laws) for white passengers.

Four days later, Montgomery’s black residents began boycotting the public bus system. King was instrumental to the boycott’s planning and execution, from his office in the church basement. The boycott ultimately lasted 13 months until the US Supreme Court ruled that segregation aboard public services like buses was a violation of the US constitution.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr delivers a sermon on 13 May 1956 at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

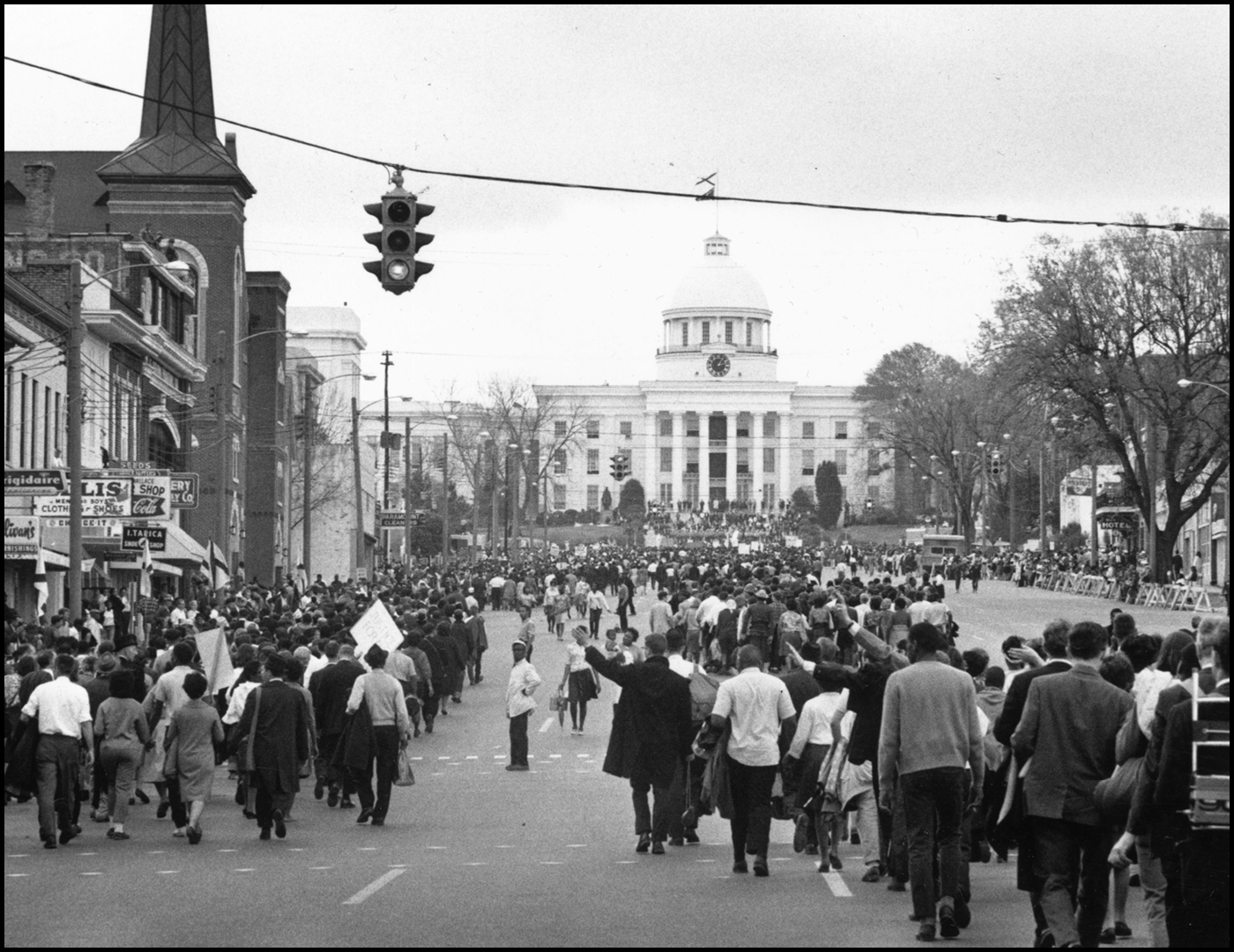

Martin Luther King, Jr and his wife Coretta Scott King lead the Selma to Montgomery March

Dexter Avenue was nominated in 2008, along with two other churches, for UNESCO World Heritage designation. In 2016, researchers at Georgia State University proposed an expanded nomination of 13 Civil Rights Movement sites across the southern US. So-called serial nominations are time-consuming because they entail preparing detailed management plans and securing stakeholder buy-in for multiple locations. Adams is tasked with shepherding the management plan for Dexter Avenue, which means liaising with the current congregation. “They are absolutely on board and support the nomination,” he says.

The building itself is well-preserved, so Adams’ primary focus is the surrounding area, known in UNESCO parlance as a buffer zone. When approving World Heritage Sites, UNESCO committees want to ensure that a site’s historical context will be respected. In the case of Dexter Avenue, that means maintaining views to the nearby Alabama State Capitol and along the length of Dexter Avenue to a historic fountain near Parks’ fateful bus stop. “With this being a downtown area, there is concern that at some point higher buildings could be built around the church,” Adams says.

The march led by Martin Luther King Jr approaches the Alabama State Capitol

“How do we convey the significance of the neighbourhood and what it looked like?” Warren Adams MRICS, City of Montgomery

Alabama State Capitol

City of Saint Jude 2048 W Fairview Ave, Montgomery, AL 36108

Despite a US constitutional amendment approved in 1870, local governments in Southern states had effectively prevented newly enfranchised African American citizens from exercising the right to vote. This was done through legal manoeuvres and using violent intimidation. In March 1965, some 600 protesters plotted a 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery to press their case on the steps of the state capitol.

After multiple false starts, and attacks by the police and vigilantes (which in one case killed a Unitarian minister), a crowd numbering 25,000 reached the Capitol on 25 March. The night before, they made their fourth and final campsite on the grounds of City of Saint Jude Catholic Church on Montgomery’s outskirts. The campus was home to a hospital serving the African American community; King’s children were born there. By then, the Selma to Montgomery March had become a national phenomenon. Top musicians like Harry Belafonte, Leonard Bernstein, Nina Simone, Tony Bennett and Joan Baez played a concert for the weary marchers.

Today a road sign marks the occasion without even mentioning the march’s name. The patchwork interpretation is indicative of challenges to convey the historical events on what is officially the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail. But anyone retracing those important footsteps now would encounter busy roads, derelict buildings and no sidewalks.

Sprucing up the trail ahead of the march’s 60th anniversary in 2025 is a priority for Adams and his team, which recently applied for funding to install sidewalks, bus shelters and internet access along the Montgomery section of the trail. “We’re very conscious of the fact that we should have more signage as people enter the city,” he says. His office is also working to convert substandard apartments on the site into renovated affordable units for older persons amid a housing shortage.

The City of Montgomery isn’t the only entity taking notice. In November, the National Park Service released the results of a study that found 26 nationally significant sites along the trail route, which could provide the basis of a future national park, the strongest level of federal investment in historic preservation.

Peacock Tract Intersection of I-85 and I-65

The head of Alabama’s roads department made his feelings clear on his business card: “I Stand for White Supremacy and Segregation.” When the federal government unveiled its interstate highway system, Alabama, like many other states, steered highways through prosperous African American neighbourhoods. After the I-85/I-65 interchange was built, some argue as retaliation for the neighbourhood’s civil rights activism, the Peacock Tract was never the same. But slowly its history is being uncovered and a second life may yet emerge.

“It’s a huge challenge,” says Adams. “How do we convey the significance of the neighbourhood and what it looked like? How do we bring back the experience of what it was like living and working here when so many buildings are gone?”

Adams is working with what is left. At the start of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Mount Zion AME Church hosted a key leadership meeting. Today the church built in 1899 is vacant and fenced off, the congregation having moved away from the highway’s shadow. But successive public and private grants over the last 20 years totalling in the millions of dollars have put on a new roof, renovated the basement and installed fire sprinklers. It may become a civil rights museum, although Adams is cautious about the long-term financial sustainability of that plan.

Across the tangle of concrete overpasses sits the Loveless School, built in 1923 as the first junior and senior high school for African American students. It too sits vacant, but in good condition. The city is in talks about converting the building to affordable housing, but any conversion will require an environmental study to see if the noise and pollution from the nearby highway is tolerable for residential use.

As this work proceeds in the Peacock Tract and along the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, Adams has proposed designating cultural rather than historic districts. He is sensitive to the burdens that historic landmarking places on property owners like architectural review boards. He seeks to balance heritage preservation goals with the need to revitalise communities who suffered intentional disinvestment.

Rosa Parks statue

“Montgomery was thrust into the national spotlight when Rosa Parks was arrested after refusing to give up her seat in the ‘coloured section’ of a bus.”

Rosa Parks Museum

Streets of Montgomery

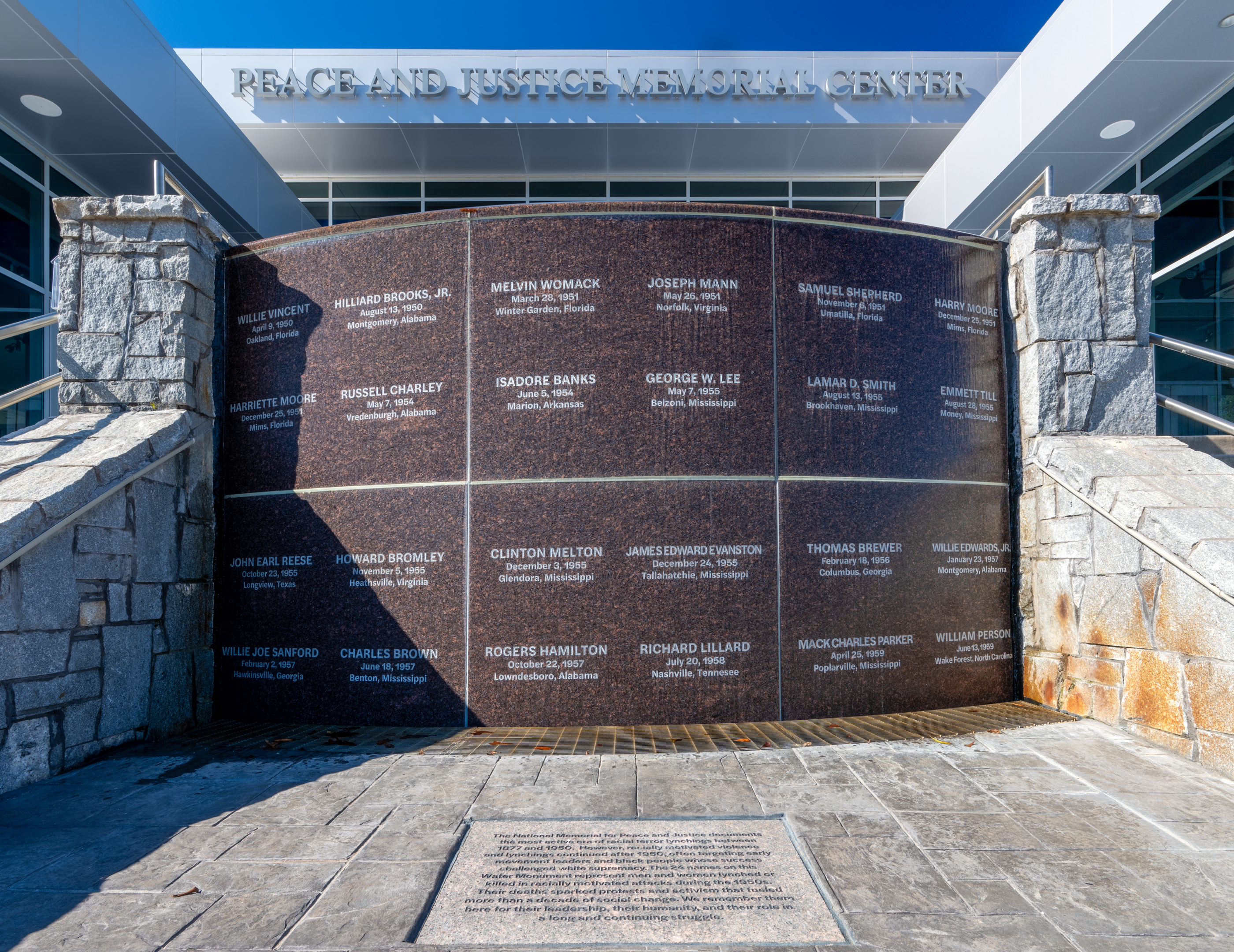

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice 417 Caroline St, Montgomery, AL 36104

The period from 1877 (after US soldiers retreated from the South and marked the end of the post-Civil War Reconstruction) to 1950, when Civil Rights activism took off, marked a reign of terror for black citizens in the 12 southern states. During this time, more than 4,000 unlawful killings of men, women and children took place. These executions were known as lynchings and they were symptomatic of the social, political and cultural order of the era.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) has raised international attention to this dark blemish on US history with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Designed by the EJI in partnership with artists, architects and builders, the six-acre site memorialises every person who fell victim to lynching. It is a monument at the scale of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin and the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg. Its debut in 2018 was a watershed moment for Montgomery, which had long embraced its role in the Civil Rights Movement but not necessarily reconciled with the ugliest elements of the South’s past.

For Adams, the memorial’s existence is proof that Montgomery’s civic identity is understood with eyes wide open. “I find everyone recognises the history, but the difference is that not all of it is celebrated,” he says. “The city has a chequered history, from slavery to the Confederacy to the Civil Rights Movement.”

While the memorial is a greenfield site, it sits in dialogue with the nearby Legacy Museum. This museum tells the 400-year story from enslavement to codified segregation to mass incarceration, on the site of a former cotton warehouse where enslaved black people laboured.

It’s a source of great pride for chartered surveyor Adams that he is responsible for looking after so many significant historical sites in Montgomery.

“To find myself in this position where I can actively contribute to what many people say is one of the most historic cities in the country, and possibly the world, is something that I’ve worked for since a young age,” he says.

“The city has a chequered history, from slavery to the Confederacy to the Civil Rights Movement” Warren Adams MRICS, City of Montgomery