Doris Brown never expected the water to reach her home. Raised a metre above ground level by a concrete block, her three-bedroom, single-storey house hadn’t flooded since she moved in as a teenager in the 1960s. But, in 2017, as Hurricane Harvey raged for a second day across her neighbourhood in Houston, Texas, Brown was in for a shock.

“The water started coming in through the back. Then I heard a crash — the roof had fallen in,” says Brown, 71, an activist and great-grandmother. “I’ve never seen anything like it. The water was just gushing over my clothes, and then the bathroom ceiling fell in too.”

Some of Brown’s neighbours rushed over with cans of food that were being stored for the local food bank to elevate her furniture above the rising water. Brown waited out the next few days — surrounded by flickering candles and sloshing around in ankle-deep grimy water — until the flooding receded enough for her son to drive over to rescue her.

About a week and a half after the storm, the carpet still wet, a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) representative came to assess the damage. But the agency refused her an award, saying that the roof collapsing in two rooms was due to “prior damage”.

Brown lives in the Fifth Ward, a low-income, predominantly black neighbourhood in the north east of Houston. Like most of those in her area, she had no flood insurance, and was told that her home contents insurance was insufficient. Unable to move or to afford a refit of her house, she had no choice but to stay in her home, despite it developing a serious mould problem.

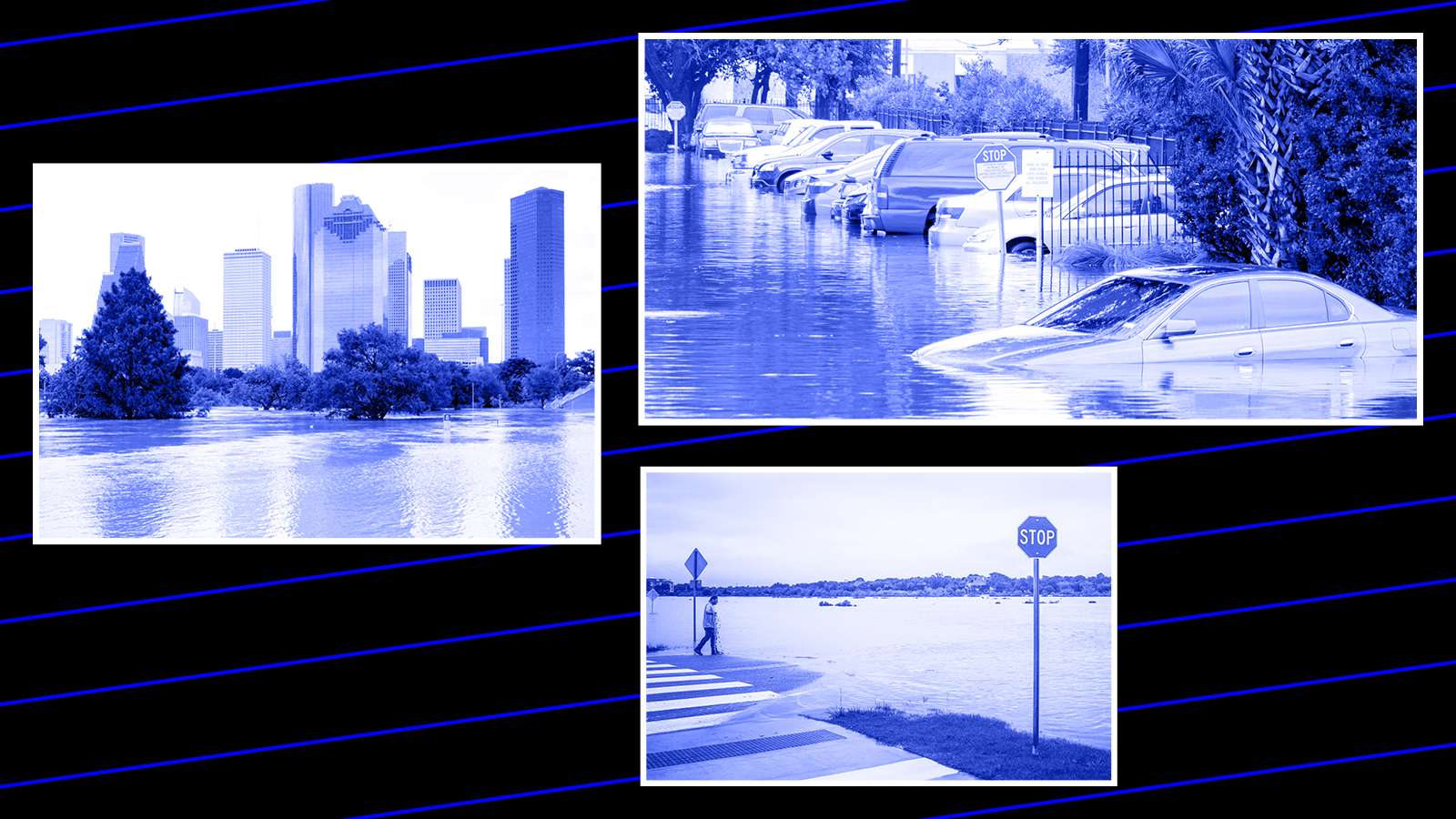

Climate change makes floods increasingly frequent and severe: a storm of the magnitude of Harvey, the US’s largest-ever rain event, is now six times more likely to occur in any given year than 20 years ago. This means the number of people in Brown’s predicament is increasing. Globally, floods are the primary source of disaster loss and damage. They exacerbate inequalities and are most devastating for low-income and marginalised communities, who live in areas with poor infrastructure and lack the funds to recover.

Homeowners face $19 billion per year in damages from flooding across the US. In Houston only 14% of people had flood insurance, and reconstruction cost, by one estimate, an average of $150,000. Few people have those kinds of savings in the US: only 37 percent of adults have enough savings to cover even a $500 emergency expense. FEMA awards small sums of money, but the average has dropped precipitously.

Many people affected by floods are either uninsured or underinsured, either because of a lack of awareness of their risk, and a suitable policy to cover it, or the prohibitive cost of insurance premiums and deductibles. Even those with insurance can find that their policies don’t cover the eventual damage they suffer: Brown says many in her neighbourhood with flood insurance were shocked to find they weren’t covered for damage from Harvey, because water came in through the roof rather than at ground level.

“People didn’t know what their risk was. Because generally maps in the US have taken historical data to determine what risk is as opposed to being forward-looking. Or people will know their risk, but they don’t have the funding to address that,” says Liz McCartney, chief operations officer at SBP, a non-profit organisation that helps people to rebuild in a resilient way after disasters across the US. SBP concentrated heavily on Houston’s Fifth Ward after Harvey.

Floods are the primary source of disaster loss and damage. They exacerbate inequalities

SBP helps people limit future damage by following the Fortified Home standard, which incorporates water-resilient flooring and cabinetry, roofs that can withstand typical winds and storms in the region, and elevated electrical and mechanical systems.

“The ideal scenario is that we would reconstruct, start from the ground up, and build to meet or exceed flood elevation,” says McCartney. SBP, which runs on donations, is hardly ever able to afford to do this; instead, it often repairs homes at risk of re-flooding again. “We work with people who don’t have anywhere else to go.”

SBP works with those who are uninsured, underinsured, or victims of contractor fraud. They overlay maps of areas affected by storms with social vulnerability indices to pinpoint the neighbourhoods they should focus on immediately after a disaster.

“A lot of the inequality harks back to a practice called red-lining. Generally, those are the communities we find ourselves working in,” says McCartney. So-called ‘red-lined’ areas, which land appraisers judged as “undesirable” in the 1930s due to the high proportion of Black or immigrant residents, suffer from disproportionately higher flood risk today. McCartney says the racial inequities are systemic: white neighbourhoods tend to increase their wealth after a disaster while communities of colour face net losses. "There are a lot of low-income households that are under-compensated by FEMA. There’s a fair amount of unconscious bias when assessors go out.”

Low and median-income households’ recovery trajectory starts with the FEMA award. An insufficient award, or no award at all, can mean a long and expensive recovery. When a whole neighbourhood is slow to recover, property prices drop and the population drops.

Usually, assessing the impact of a storm is based on applications for FEMA assistance, which is assessed by door-to-door visits. But this excludes people who were delayed in applying for grants, as well as rejected applications. SBP is critical of FEMA’s reluctance to use aerial damage assessments. “Using flyover imagery and a lot of mapping tools could significantly improve accuracy and speed," says McCartney.

The City of Houston tried to correct this imbalance by partnering with the data organization Civis Analytics and engineering consultants Dewberry to analyse the costs of damage through various data streams: rainfall data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; data from the county’s assessors’ database to log what material buildings were built with; and land-use data to record which surfaces are impervious. They then reconstructed the hurricane using predictive technology — and identified an additional 130,000 hurricane victims and $16 billion in residential damage. This led to an additional $2 billion more in federal recovery funding.

Brown says she doesn't know anyone who received a FEMA award in her neighbourhood, although many applicants there are still fighting appeals. It was two years before a local organisation, West Street Recovery, came in to assess her property and saw the extent of the mould in her home. They gutted and refitted the house for free. She now has a tiled floor and the plasterwork starts a few inches above the ground, with a water-resistant skirting board.

Harvey was a turning point for civil society in Houston; in the absence of institutional help, the community banded together. Those ties were crucial when Storm Imelda struck in 2019, and during the polar freeze in February of this year that burst pipes and caused power cuts. Brown now works with West Street Recovery and helps with disaster preparedness in her community, readying generators, getting stocks of advance prescriptions for those reliant on medication, and distributing battery packs.

“Whatever happens, we’re going to be ready,” she says. “We’re branching out all over. We're teaching other states how to prepare for these disasters.”

White neighbourhoods tend to increase their wealth after natural disasters while communities of colour face net losses

Building resilience and reducing flood risk

What strategies are available to the profession to mitigate the effects of flooding at the individual property level? Read more here

_1%20Mar.jpeg)