Illustration by Mark Pernice

Since the general election in July, the UK’s prison system has had a lot of media coverage.

The appointment of James Timpson, CEO of Timpson Group and former chair of the Prison Reform Trust, to the position of prisons minister got the ball rolling on plans for major reform. Then came the early release of 1,700 inmates in September to ease prison overcrowding and a further 1,100 in October.

The chronic lack of space in ageing prisons, combined with the number of inmates – currently just over 88,350 for England and Wales – has been a problem for a number of years.

The collapse of construction firm ISG (also in September) that held 69 government contracts totalling £1.8bn, including one for a new prison, brought unwanted new for the sector. Although the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) stated at the time it has “robust contingency plans in place to mitigate the impact on our prison and court estate of ISG going into administration.”

Yvonne Jewkes, one of the world’s leading experts on rehabilitative prison design, says media coverage “has never been higher in my lifetime”. The professor of criminology at the University of Bath recently published a book, An Architecture of Hope, which explores prison design and how the spaces people inhabit nurture or damage them. “My primary aim is making people think differently about prisons and who we send there.”

Jewkes has been the go-to consultant on various prison building programmes in Ireland, New Zealand and Australia. She has also been advisor to the MoJ, HM Probation and Prison Service (HMPPS) and architects Bryden Wood on early design plans for HMP Five Wells in Northamptonshire (also known as Wellingborough Prison).

Opened in 2022, Five Wells is considered a poster prison of the future, following on from the groundbreaking HMP Berwyn in Wrexham that opened in 2017, where Jewkes was also an advisor. The £220m Berwyn facility was billed as a ‘super-prison’ and a move in a new direction for prison design focusing on rehabilitation rather than incarceration.

Meanwhile, Five Wells, costing £253m with a 1,600-capacity, was the result of intensive research from all those working within and around the prison service and is part of a major prison building programme – one of the biggest since the Victorian era. Overall, £4bn is being invested in creating 20,000 modern places, with an aim to complete around 10,000 by the end of 2025.

It was also a chance to develop a new type of prison environment using a platform-based Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) approach. The core purpose being to increase the likelihood of rehabilitation and reduce re-offending rates.

Modern prison design

There are undoubtedly sensitivities around the construction of these facilities, such as striking the balance between institutionalisation and human comfort or between needing the facilities and placating worries from surrounding residents.

But for Jaimie Johnston, director at Bryden Wood, locking people up is penance enough. “The fact you've lost your liberty, that's the punishment,” he says. “Don't make it even worse by putting people in these horrible situations.”

In 2016, Bryden Wood was commissioned by the MoJ to work on the overarching design and delivery for the programme of prisons, and given six months, not to design a facility, but to look at everything that would influence the design: “We spoke to prisoners, prison support groups, those who provide legal advice to prisoners, the cleaners, the catering staff, the control and restraint teams, to understand what we could do,” says Johnston.

The result was cells being arranged in smaller groups around sculpted courtyards with carefully chosen greenery, doing away with the traditional Victorian-style gallery cell blocks (known as K-blocks because of their layout), in favour of house blocks. And taking bars out of windows, which are fitted with ventilation panels the prisoners can control, while each floor has its own tea point, small cardio gym and classroom.

“Autonomy and self-determination are big factors … everything was geared around this question of how we make this as normalising an environment as possible while maintaining security and safety,” says Johnston.

Bryden Wood also worked with the operational staff on the typical problems encountered and how they could design them out. Prototypes were built to test out the cells for anything the prisoners could use to cause destruction or to harm themselves. “We designed things which are quite elegant but also happen to be incredibly robust,” Johnston says.

What they also found at HMP Five Wells was how the new facilities were welcomed by those living and working nearby: “Our expectation was that people would be fearful or up in arms,” says Johnston. “Actually, no one thinks that prisoners escape anymore, so no one's really bothered. Visitors will come, people come and visit the friends and family, the local cafes. People were generally quite supportive of it.”

What those living nearby didn’t want, was for Five Wells to look like a jail. “We don't have the massive roofs, and it has bigger windows, so it looks more like a student housing block.”

“It is not just a case of 'spend as little as possible, and do the minimum maintenance,' it’s about improving the prisons and their carbon position” Jenny Beilby MRICS, AtkinsRéalis

Prisons with character

Victorian-era prisons are still very much in use in the UK, with 32 operating in England and Wales that were built between 1837 and 1901. Housing around 22,000 inmates, they include the well-known names of Pentonville, Belmarsh, and Wormwood Scrubs.

Despite being labelled as crumbling and rat-infested in some media coverage, “there's a lot to be said for old buildings,” says Jewkes, who is coming to the end of a collaborative research project called The Persistence of the Victorian Prison. “What we found is many prisoners, and some prison staff, much prefer being in a Victorian prison because they have character.”

“Yes, they come with problems: rubbish, vermin, often very ancient heating systems so, it's a complex picture. Some people would prefer them to be closed for those reasons because maintaining Victorian heating systems is very costly.”

The maintenance of older prisons is the job of AtkinsRéalis. Jenny Beilby MRICS, the company’s framework manager for the MoJ account, says the reality in the UK is there are simply a lot of prisons, and “with the best will in the world, there will never be enough new build prisons to replace them.”

This means, says Beilby, the MoJ needs to maintain the Victorian buildings to a quality and standard needed for the best prisoner experience, within the constraints of the age of that building, and any other on-site limitations.

Sustainability bias is a crucial element when undertaking maintenance projects, she says: “It is not just a case of 'spend as little as possible, and do the minimum maintenance,' it is about improving the prisons and their carbon position,” says Beilby. Projects include removing gas supplies and swapping for fully electric or considering air source heat pumps for boiler replacement schemes.

Next year, the UK is set to complete its first 'green' prison – HMP Millsike in York, which will house 1,500 inmates. It will use 75% less energy than older prisons, run solely on electricity, and use solar panels, heat pump technology and more efficient lighting systems.

Other sites set to follow will strive for the same standards and ideals set out by Five Wells. “We’ve definitely had an impact,” says Johnston. House blocks are being rolled out as standard, prisoners are in the smaller cohorts, bars on windows are gone, management is more accessible: “Those are things now baked into the design however they choose to build them.”

Regardless of how these new prisons are built, Jewkes believes there needs to be a complete root and branch rethink of what prisons are used for: “Why is it our default punishment? Should we be thinking radically differently about what we do with convicted offenders?”

Until that happens, the MoJ, working with its architects, designers and consultants, will strive to do what it can with the current Victorian stock and the new builds to give prisoners a chance at rehabilitation and a new start in life.

“The fact you've lost your liberty, that's the punishment. Don't make it even worse by putting people in these horrible situations.” Jaimie Johnston, Bryden Wood

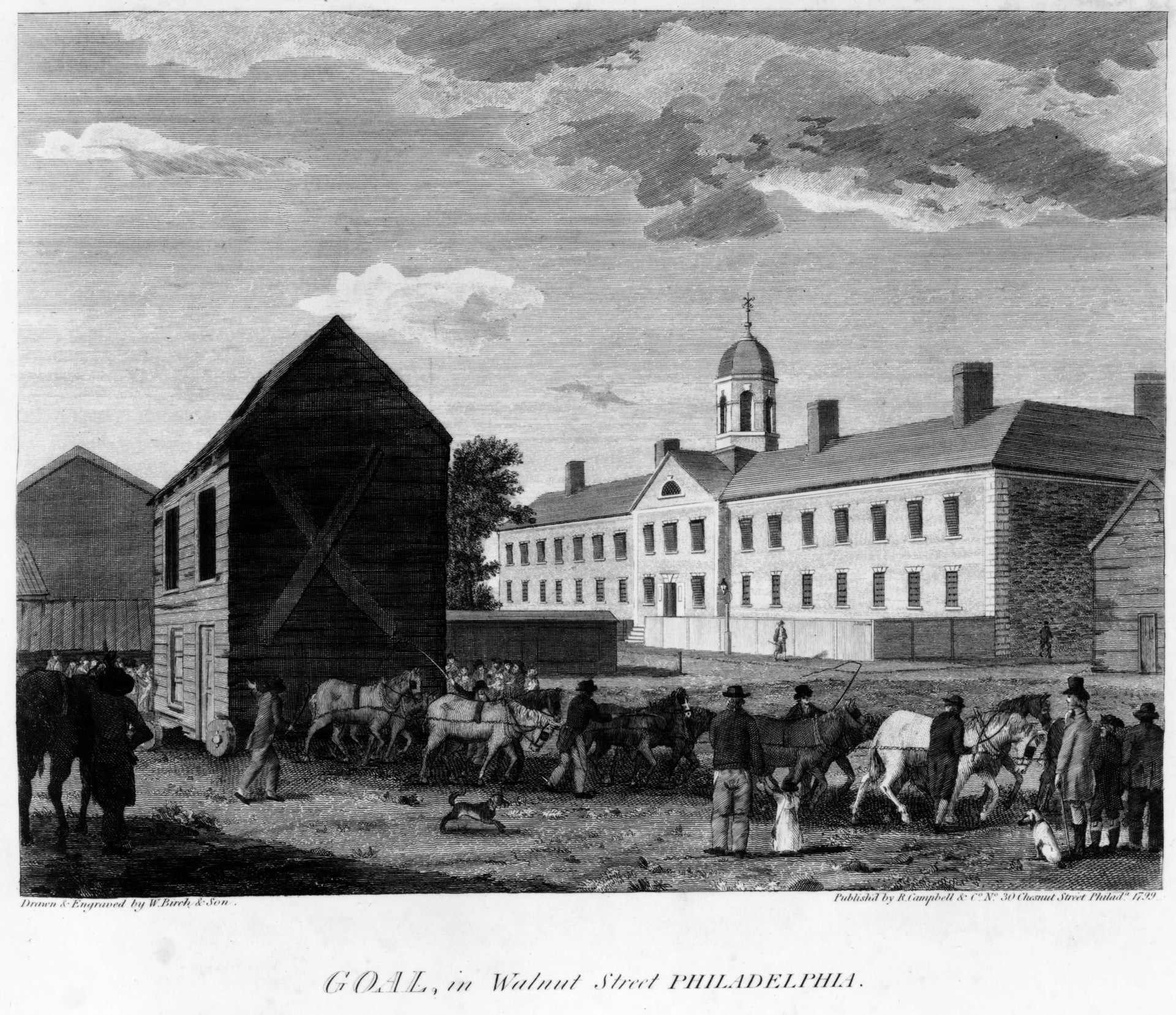

1799: A jail in Walnut Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Original Artist: By William Russell Birch. Image: MPI/Getty Images

North American prisons

The first US penitentiary was Philadelphia’s Walnut Street Prison in 1790. Today the US has just under 6,500 facilities across federal, state and local systems holding 1.9m people, while Canada has 58 federal correction institutions, with 35,500 inmates.

There are big building plans for both North American countries. Ten major courthouses and jails for Canada, and billion-dollar correction facilities planned for the US, including a $1.2bn super-prison in Indiana, that are making prisons a huge part of the current construction landscape.

Attitudes toward prison design have evolved throughout the history of America, says April Pottorff, a principal at DLR Group who has 40 years of experience designing buildings for the justice system: “We no longer conceptualise prisons as warehouses, but as places for rehabilitation.”

An important part is placing prisons in urban areas: “In America especially, the standard model has been to place prisons far outside of major towns and cities,” says Pottorff. “If we want to rehabilitate and believe in a rehabilitative justice model, that means keeping people in custody within their communities to have close interaction with their families and make connections to services in the community, [establishing] a continuum of care once released.”

Ultimately, says Pottorff, each facility, should reflect the local culture, values, and belief system, because each one depends on the engagement of the community to fulfil its rehabilitative mission: “These facilities can and should be designed to be good neighbours as they’re a part of our civic infrastructure just like the fire station, courthouse, and library.”