Illustration: James Pop

The world is in the grip of the deepest economic recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. That was the assessment of the International Monetary Fund in its June economic outlook, which predicted that over $12.5tr would be lost through the recession and subsequent slow recovery this year and next, compared with what economic output was predicted to be at the start of this year.

This may only be a foretaste of the economic damage to come: it pre-dates the uptick in COVID-19 cases in many parts of the world in the summer of 2020, and the IMF also predicts that, if a second wave of the virus strikes early next year, there could be almost zero growth in 2021. Even as economies grow back, the fund points out, longer-lasting scars will be left behind in the form of long-term unemployment, disrupted educations and corporate insolvencies.

In an economic slump, the usual response for governments is to invest in infrastructure, both as a short-term stimulus and to support jobs and growth in the longer term.

Industry sources have been quick to talk up the benefits of an infrastructure stimulus. Advisory firm EY has estimated that stopping construction activity during the pandemic would depress the economy in areas including South Korea, China, Australia and the EU by at least 7% compared with a lockdown during which construction carries on. In the US, the figure rises to 10%.

“Conversely, when economic restrictions are eventually lifted across the globe, preserving construction activity, coupled with accelerating infrastructure investment, spills over to the broader economy and boosts recovery,” EY argues.

Where will the cash come from?

But investing in infrastructure is never straightforward. And, while the sector as a whole underpins economic activity, specific projects do not always generate the desired economic outcomes. Projects usually take several years before reaching the construction stage, so that any local jobs and spending they create may come too late to address a slump; and if poorly selected, their costs may outweigh their benefits and displace more useful activities, as recent academic research has found.

All infrastructure is ultimately paid for either by taxpayers or end users through fares and utility bills, but both of those sources are looking impoverished. So how should an infrastructure stimulus be carried out?

“The key thing right now is getting cash out into the economy. We need to make sure that spending on shovel-ready projects is one key strategy,” says Jennifer Brake, director at PwC’s global capital projects and infrastructure practice. “You can see that being deployed in places like New Zealand.” New Zealand announced NZ$3bn (£1.5bn) of new spending on infrastructure in May as part of a recovery budget. Canada’s federal government has also unveiled additional funding for infrastructure improvement works, plus incentives for new projects that can start in the near term.

For Don Stokes, a Singapore-based infrastructure partner at law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, the infrastructure need in developing Asia is so big that there is little risk of projects being unproductive. “Take Vietnam or Bangladesh. They desperately need road connectivity, rail connectivity, new power-plant generating capacity and upgrades to the grid,” he notes.

As well as finding shovel-ready projects, Brake says that another challenge is making sure the spending reaches the places it is meant to reach – protecting local supply chains. “I think we’re seeing some governments talk about how they can break up some of those bigger projects into smaller contracts to really help facilitate some of that spending down to smaller parts of the supply chain,” she adds. Such projects might be deemed “shovel-worthy”, rather than shovel-ready.

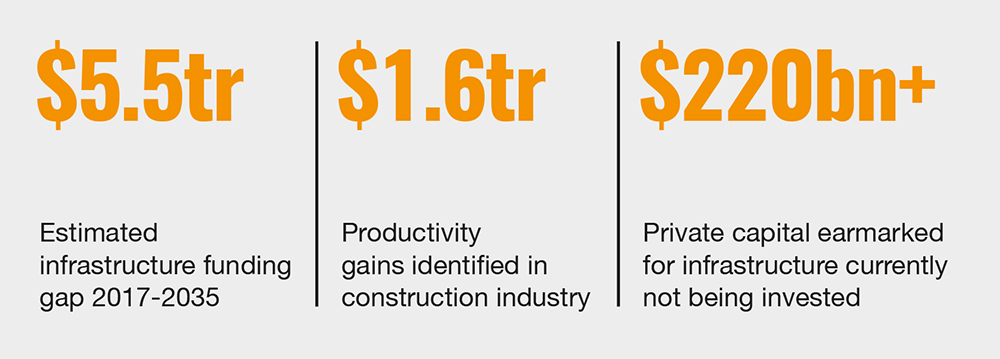

Project preparation will also be vital if governments want private finance to complement public spending. Consultants often talk of an infrastructure funding gap between how much is invested globally and how much is needed to allow economic growth to continue (or resume, in the current situation). The problem is difficult to quantify, because the figures are so huge and they depend on constantly changing factors, but McKinsey put it at $5.5tr beween 2017 and 2035.

Time for a rebalance

In May, a report from RICS’ World Built Environment Forum (WBEF) identified several barriers to getting more projects delivered with some of the $220bn-plus of private capital earmarked for infrastructure investment (both in new and existing assets) but not being invested. The report was written before the wave of lockdowns spread across the world but, according to its lead author, Martin Haran of Ulster University, its premise and recommendations still stand.

“Has it in any way dispelled or mitigated the need for infrastructure investment? Absolutely not; if anything it’s highlighted the fact that in certain sectors, particularly healthcare and social care, there’s been a huge sustained underinvestment,” Haran comments.

He adds: “I think coming out of this pandemic, we will see some degree of rebalancing, because so much [focus] over the past decade has been on economic infrastructure… probably somewhat to the detriment of our social infrastructure.” Haran argues that governments have not done much work in forecasting future population demands for social infrastructure, such as social care or social housing.

Governments may be less inclined to rely on private finance right now because of two factors: the weakness of many construction companies, who are asked to take on construction risk in private finance projects, and the historically cheap borrowing rates – sometimes with zero or negative interest – that some developed countries are enjoying.

“There is a strong argument to say that from a value-for-money perspective, there is a case for government go out and borrow more, and become heavily involved in funding infrastructure… but many of the largest economies in the world are already heavily indebted,” Haran says, arguing that high public spending in response to the pandemic will curtail borrowing appetite.

“In certain sectors, particularly healthcare and social care, there’s been a huge sustained underinvestment” Martin Haran, Ulster University

Funding the right projects

Where governments do seek private finance for their infrastructure procurement, the most common complaint investors have (and one picked up by the WBEF report) is a lack of suitably structured projects to invest in. The World Economic Forum’s global future council on infrastructure spent much of last year trying to address this issue, as Joseph Losavio, infrastructure specialist at the forum, explains.

“To help close the investment gap, we’ve focused on mapping, analysing and raising awareness of the various project preparation tools available, as well as creating an open-source tool aimed at upstream decision makers,” he says. This tool is intended to help policy-makers decide whether to procure their projects with private finance, reducing the risk of poorly selected projects being offered to investors and not getting done.

Encouraging green growth

However these infrastructure projects are prepared and financed, another issue remains. Stimulating economic growth should not supersede addressing a more pressing emergency: climate change.

Much has been said about how government and the infrastructure industry’s response to the pandemic could spur on the transition to renewable energy generation? but this cannot be taken for granted. Private investment in renewable energy was healthy beforehand and should continue, although an economic downturn may reduce demand for new generation from corporate clients, which plays an increasingly important role.

Current rock-bottom oil and gas prices will not help, particularly in developing Asian countries, says Stokes. “Pricing has to play a role in the energy transition. Cheaper oil and gas will not accelerate the energy transition; if anything, it will slow it, because when it’s so cheap to use gas, people will continue to use gas.”

But Fintan Whelan, a Dublin-based renewable energy developer, argues that the energy transition should play a role in the recovery, if governments can put the right strategy together. “Financing the post-COVID-19 – or with-COVID-19 – economic recovery is going to be expensive, and climate change is already expensive. So why not do the one in a way that sorts the other out?” he asks.

Whelan points out that a concerted effort to roll out electric vehicle charging points will create additional demand for power. And domestic energy efficiency policies, which in the case of Ireland extend to installing rooftop solar panels, can be a job creator all over the country. “A lot of climate change action can be dressed up as a stimulus, and that’s important because you’re ticking two boxes.”

Ultimately, the scale of the infrastructure funding gap is such that simply throwing more money around will not close it. The existing spending has to go further. McKinsey has identified a variety of areas where “infrastructure productivity” measures could save 40% of infrastructure spending; separate but overlapping analysis found $1.6tr of productivity savings in the construction industry.

“A lot of climate change action can be dressed up as a stimulus, and that’s important because you’re ticking two boxes” Fintan Whelan, renewable energy developer

The need for better data processing

For Brake, productivity can be increased at several points in the value chain, from project planning (including demand forecasting) to construction methods, resource deployment and supply chain management. But all of this relies on more and better use of data.

And therein lies a problem: the same engineering and construction sector that has suffered during the lockdowns has under-invested in data processing. “How can you make sure those construction companies have the room in their own finances to be able to invest in those kind of technologies or digitising methods – because historically, it’s been a sector that has been trying to catch up with others? It’s a difficult thing to ask right now,” says Brake.

Although financial investment incentives in new technology in construction are being addressed – in the UK and other markets, by bodies such as the Construction Innovation Hub (CIH) – professional innovation is also key. That is why RICS has developed international data standards, such as International Construction Measurement Standards (ICMS), to enable comparable and consistent data collection. For these standards to have added impact, RICS and BCIS are also promoting an important data-sharing debate with governments, industry and the profession, says Alan Muse FRICS, RICS global director of built environment. Private investment in this area will also depend upon sustainable businesses and by addressing such industry concerns as lowest -ost procurement. Here the RICS is also working with CIH to develop a ‘value toolkit’ for public and private sector procurement decisions – signalling a dramatic change in procurement practice.

It may be another area where government has to step in and provide funding. Now more than ever, private finance relies on public sector support.

What impact could a common data standard have on the global construction industry’s ability to deliver resilient, sustainable infrastructure projects at scale, on time and on budget? Join the discussion in a forthcoming World Built Environment Forum webinar on 7 October, 10:00 – 11:00 BST