When the internationally renowned architect, Lord Rogers, died in December, he left a legacy of instantly recognisable buildings.

The Lloyd's building, the Leadenhall building (aka the Cheese Grater) and Millennium Dome, all in London; the Senedd building, in Cardiff; the European Court of Human Rights building, in Strasbourg, Madrid’s airport and the skyscraper that replaced New York’s World Trade Centre towers are among his most famous designs. But arguably the standout is the Pompidou Centre, that sprawls across five acres of central Paris.

Situated in the Beaubourg area of the city’s 4th arrondissement, near Les Halles, rue Montorgueil, and the Marais, it is an example of an “inside-out” building and has as many critics as fans. But, whatever the critical perspective, it undoubtedly has had an impact on its surrounding area.

“The Pompidou Centre is a game changer. Not necessarily for the originality of the idea but because a city had the audacity to build it,” says Chris Harding, chair at architect firm, BDP. “It is wonderfully impractical - causing further debate and rolling of eyes.

“Environmentally, it wouldn’t cut it by today’s standards but in the spirit of the giant Meccano set it looks like, it should be completely flexible, adaptable and even capable in today’s parlance, of ‘disassembly’ and ‘reassembly’,” says Harding. Not that any of this matters because “it is a treasured national landmark and will be well-used and looked after for generations to come.”

The centre was the vision of its namesake, Georges Pompidou, French prime minister, from 1962 to 1968, then president of France between 1969 and 1974. But there were many problems facing President Pompidou's dream of a national cultural centre, according to the cometoparis website: “Not least was that by the 1970s, Paris had lost its place as leader on the contemporary arts scene to New York. To regain the top spot, the French capital needed an original space that would be instantly recognised around the world.”

To solve this, the call was put out to the great and good of the architectural and design world to come and put France back in top spot. Out of 681 competition entries, came the appointment in 1971 of Richard Rogers, who was part of a dream team that included Renzo Piano - the man who would go on to create London’s Shard.

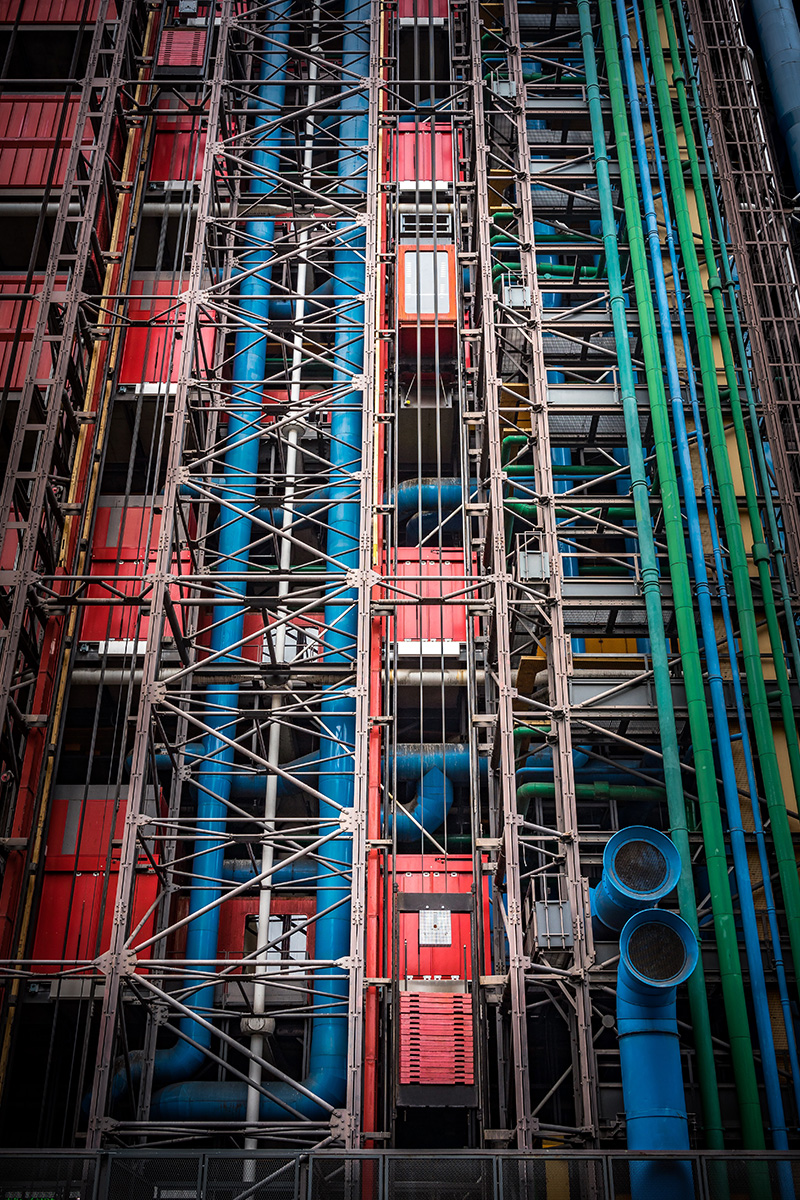

Their inside-out design literally exposed the interior of the building – features such as the circulation, mechanical, structural systems – on its exterior. It was the first of its kind and was a style that they used again at the Lloyd’s building a few years later.

Costing almost 100m francs (€15.25m; $17.5m) to build, the Pompidou Centre, inaugurated in 1977, achieved what it was created to do: to bring together different forms of modern art and literature in one place and focus international attention. It houses the Public Information Library and is also home to the National Museum of Art, which houses some of the great works of the 20th century including pieces by Picasso, Warhol, Kandinsky, Kahlo and Chagall.

But not everyone is taken in by the Pompidou Centre. “Rogers’ impression that he is creating innovative, humanistic, even whimsical, buildings simply does not hold up,” says Ann Gray FRICS, of Gray Real Estate Advisors. “Far beyond stylistic differences, these buildings reveal a complete focus on the object as opposed to context, on interior as opposed to site.

“The street-level experience near them is nothing short of dystopian and the poor disoriented pedestrian is left to roam as there is no perceivable ‘front door’. The massing appears to be determined by some tangential idea unrelated to anything but the architect’s vision; there is no observable hierarchy to the spaces and forms.”

Certainly, when the centre first opened, it was by and large mauled with critics labelling it an “oil refinery”. It was considered shocking, provocative, and, as Gray points out, insensitive to the surrounding streets.

"It is a game changer. Not necessarily for the originality of the idea but because a city had the audacity to build it" Chris Harding, chair of BDP

"Rogers’ impression that he is creating innovative, humanistic, even whimsical, buildings simply does not hold up" Ann Gray FRICS, Gray Real Estate Advisors

Rogers himself had been quoted as saying: “Renzo says we were the ‘bad boys’ of architecture. When President Pompidou looked at the drawings, all he said was ‘Ça va faire crier’ [This is going to make a noise]; but we moved to Paris for five years, it got built on time and within budget, and it was a big success.”

While it may initially have been on budget, the cost of maintaining the Pompidou has caused increasing outrage. Over the years, keeping the building’s distinctive paintwork pristine has been a constant drain; in the late 1990s it closed entirely for three years for an €88m refurbishment; last year the cost of upgrading its famous exterior lifts was €19m; and next year the Pompidou will close again for another four years to undergo a further estimated €100m worth of work.

Rogers was right in that it is still considered a success as its 1.5 million annual visitors (pre-pandemic) testify. Despite the disdain from some commentators, the Pompidou has become one of the most famous and celebrated buildings in Paris, a must-see for tourists and a prestigious venue for performers. Its radical design meant that the city was free to enter an era of more contemporary architecture and it unarguably lifted the profile of a previously overlooked area of the city, revitalising the neighbourhood for residents and local businesses.

“It has transformed the Beaubourg area of Paris, delighting and alienating in equal measure,” says Harding. “But no one can argue with half the site being given over to a great urban space. “I like to think Centre Pompidou embodies the tenets of social sustainability – a place for all the people.”

Pompidou – the inside-out facts

It contains 15,000 tons of steel, 50,000m3 of concrete and has more than 11,000m2 of glass façades.

In 2010, it produced an equally outlandish sister museum at the small French city of Metz and further branches have been proposed – but are, as yet unbuilt - in the cities of Maubeuge and Liborne.

It has also created a temporary museum in Malaga, Spain to show some of its works and another offshoot has been planned in Brussels. There are plans to take the Malaga pop-up to Mexico City and possibly onto Brazil. The Pompidou has also loaned its name – and cultural clout - to a gallery in Shanghai.