Artwork by Caroline Dowsett in Manchester

Graffiti has come a long way since its early days as a largely illegal form of artistic expression or political protest, often painted on underpasses or neglected sites where it was easier to work without fear of getting caught.

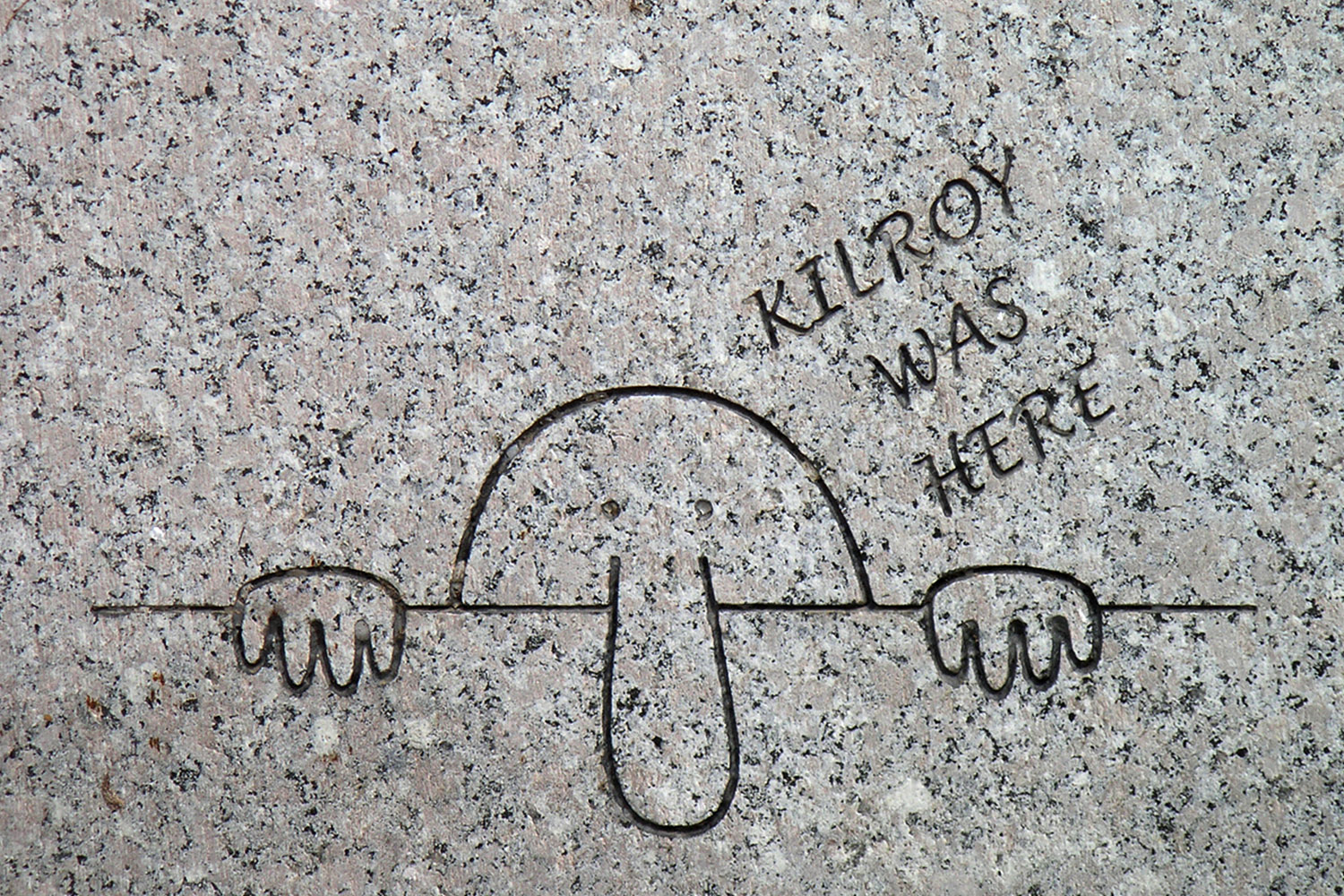

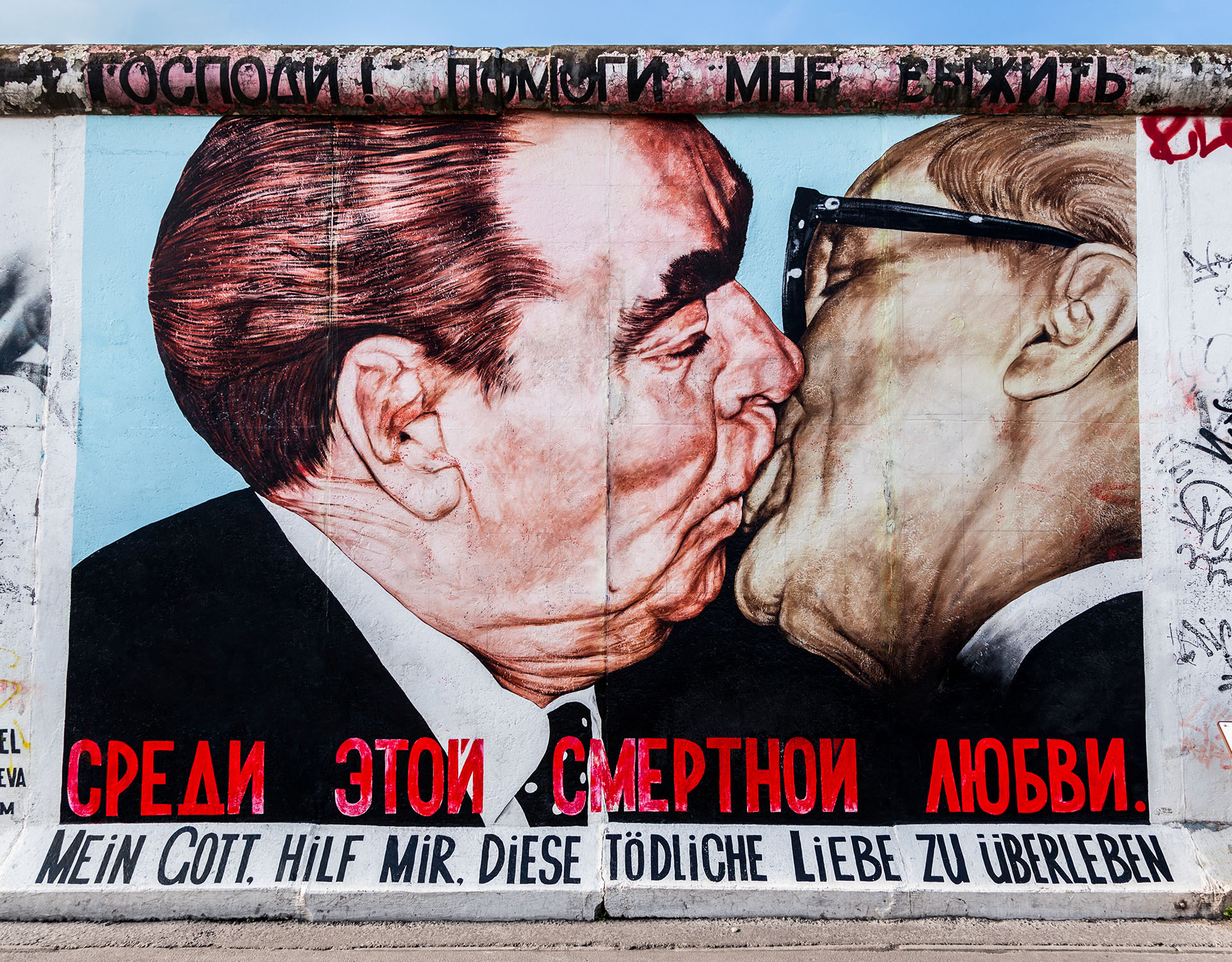

In Cold War-era Germany, painting on the Berlin Wall was itself a deeply political act and much of the graffiti that appeared on it has been preserved as an important part of history. Delve back a little further into the past and you have the origins of modern graffiti – ‘Kilroy was here’ drawings of a bald, long-nosed man peeking over a wall, which was a popular calling card for Allied soldiers in World War Two.

Also from that era is the graffitied ceiling of The Eagle pub in Cambridge, UK, where Second World War airmen used wax candles, petrol lighters and lipstick to write their names, squadron numbers and other doodles onto the ceiling of the rear bar before they flew. This graffiti in Berlin and Cambridge has taken on extra cultural value because of its historical significance.

As with many art forms that began as something existing on the fringes of society, graffiti eventually gained popularity and entered mainstream culture. There, it branched off into new forms such as commissioned street art or murals on construction hoardings. Street art is big business now and buildings owners are commissioning original works for prominent exterior walls, to add a splash of colour and creativity.

In many major cities you’ll find street art walking tours of all the best murals and graffiti an area has to offer. For a retail business, bar or café, this could be very valuable in terms of footfall and might prompt a business owner to hire someone to create a striking, tour-worthy work of art.

'Kilroy was here' engraving at the National World War II Memorial in Washington, DC. Photo by Luis Rubio

And the upside of high-quality street art doesn’t only apply to commercial businesses. Hans-Michael Brey FRICS, CEO of Urban Nation, a museum for urban contemporary art in Berlin, says: “With the help of street art projects, neighbourhoods can get a positive image by becoming a brand. In a best-case scenario, the works of art in the neighbourhood can spark a discussion among the residents, which can result in further positive effects: stronger sense of identity, less vandalism and a willingness to help each other. All of which are marks of success for a housing company.”

Brey is also on the board of directors of the Berliner Leben Foundation, which promotes art and cultural education. He says that whereas once building owners may have wanted to keep their walls clear of any street art, now perceptions have changed in the age of Banksy.

“Companies in the housing and real estate industry … use street art in a targeted manner to create a cool image for a project,” says Brey. “Big names and popular images help to support the desired development.”

The RAF room at the Eagle, Cambridge. Photo by Hitchster

“Companies in the housing and real estate industry … use street art in a targeted manner to create a cool image for a project” Hans-Michael Brey FRICS, Urban Nation

'My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love' by Dmitri Vrubel on the East Side Gallery, Berlin

'Well Hung Lover' by Banksy became the UK's first legal street art after 97% of respondents to an online survery by Bristol City Council were in support of keeping it

A light bulb moment

A recent commercial development that has employed street art successfully is The Bulb in Southampton. What was a large, uninspiring, concrete 1970s office building (formerly called Nelson Gate) beside the train station has been given a £3.5m interior and exterior revamp, which includes a giant ‘clean air’ mural by street artist Nerone.

Residents of Southampton were asked to vote for their favourite design, from a choice of three, with the winner adorning the office block for years to come. “Ultimately this mural is for the people of Southampton, it is the gateway to their city when arriving by train,” says Ryan Barber, head of offices at FI Real Estate Management. “More than 10,000 people voted so it obviously struck a chord. The building had lost its identity and was seen locally as a concrete monstrosity.

“Following the refurbishment inside, it was important that we didn’t overlook the outside. We hope we have now added some much needed colour to the city skyline and given the people of Southampton something they can be really proud of.”

FI Real Estate also took the opportunity to further the building’s ESG credentials by using CO2 absorbing paint for the mural. “The paint is a lime-based paint, says Barber. “As the paint cures, around 65kg will be absorbed from the environment.” This works out to roughly the same CO2 as three mature trees would absorb from the atmosphere in a year.

But, getting down to brass tacks, has the mural and the publicity around it generated business interest in The Bulb? Barber says yes, it has “resulted in a real upturn in enquires from people wishing to take up occupancy in the building.”

The Bulb, Southampton. Photos by Hannah Judah

“Following the refurbishment inside, it was important that we didn’t overlook the outside” Ryan Barber, FI Real Estate

The street art economy

The rising popularity of street art and crossover from being a clandestine activity means it has become part of a financially viable career for many artists. Caroline Dowsett, based in Manchester, UK is one such artist whose work is a mixture of digital art, canvas paintings, mural painting and street art.

“There is definitely a bigger demand for and appreciation of street art by a wider audience in recent years,” Dowsett says. “Especially pieces that a community can collectively enjoy and pieces that draw new people to areas. Street art and murals are so accessible for everyone, which is a beaut thing.”

The fact that companies such as FI Real Estate are willing to pay an artist to create a giant mural on the façade of an office building shows it can add a financial value to the building, as well as an aesthetic one. “The value that street art adds to a building or place is high, it contributes to a sense of optimism in and around those streets. It’s a telling sign of appreciation of creativity,” Dowsett adds.

“The value that street art adds to a building or place is high, it contributes to a sense of optimism in and around those streets” Caroline Dowsett, artist

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

A 2016 article for the RICS Building Conservation Journal called ‘Etched in the Memory’, co-authored by Alan Forster, Samantha Vetesse and John Borland, states that: “Decisions to record and/or retain are made relatively easily when the examples are ancient or have been produced by famous people. However, they are rather more difficult with relatively modern contentious examples.”

One modern example that has certainly proved contentious is on the side of a Scottish pub called the Larachmhor Tavern in Fife. A mural of a witch, commissioned by Fife Council, has proved so divisive among residents that the same council has now ordered its removal. The discord has arisen from a perceived insensitivity towards the 4,000 people (mostly women) who were tortured or executed under the 1563 Witchcraft Act in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Fife Council planning officer Chris Smith described it as “gaudy” and said it “does nothing to enhance the conservation area or the listed building”. However, SNP councillor David McDiarmid made the point: “If that had been done by Banksy would it still have been up for refusal?”