The health hazards of city living are a familiar reality for billions of people around the world. Now, stifling temperatures, made more frequent and intense by climate change, rank high on the list of concerns for many urban dwellers.

More than a cause of discomfort, rising heat levels in metropolitan areas are responsible for thousands of premature deaths each year, threatening livelihoods and damaging buildings or infrastructure originally intended for cooler climates.

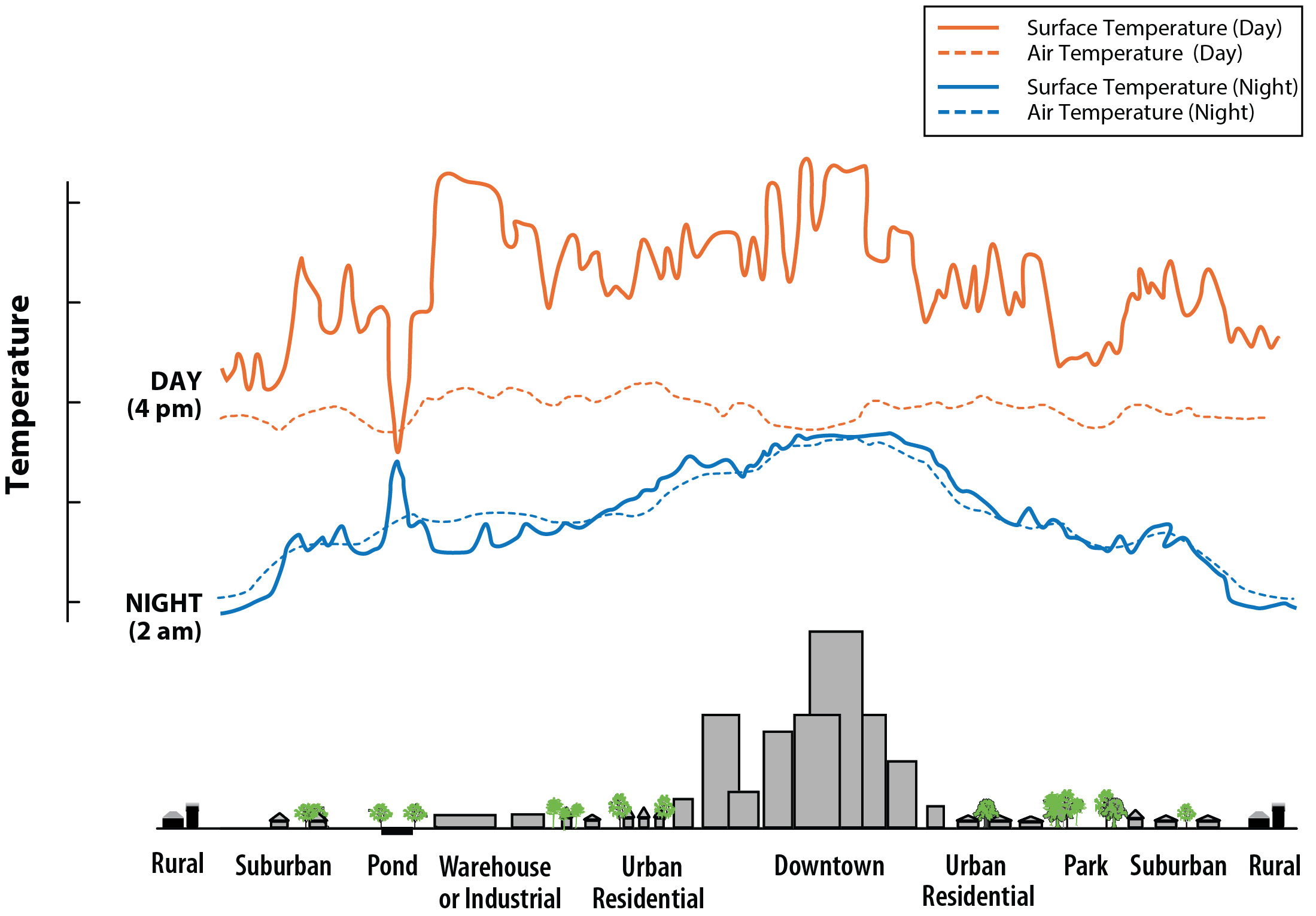

Dark-coloured surfaces on buildings and roads tend to absorb solar radiation and release it as heat, rather than reflect it back into the atmosphere. This leads to an urban heat island (UHI) effect and higher air temperatures than the surrounding countryside.

According to figures from the US Environmental Protection Agency, cities are on average between 1-7°F warmer than surrounding areas during the day and can remain up to 5°F warmer at night. With more frequent high temperatures on the horizon, urban planners, designers and engineers are under increasing pressure to transform cities with more appropriate solutions to prevent streets, buildings and residents from frying in the heat.

“This is incredibly urgent,” says Sara Wilkinson FRICS, professor of sustainable property at University of Technology Sydney’s (UTS) Faculty of Design Architecture and Building. “As urban density increases, the timeframe in which effective action can be taken diminishes every day. New policies and regulations are needed, but with just 1-2% added to the total building stock in any year it will take decades to bring the existing stock up to current standards.”

Devising appropriate and scalable solutions to extreme heat can be complicated. Increasing the use of air conditioning might seem logical, yet studies have shown it can exacerbate the problem by expelling hot air into streets, adding as much as 1ºC to outdoor temperatures. As aircon systems increase outdoor heat, it prompts residents and building managers to switch them on for longer, creating a feedback loop.

Over-reliance on aircon has fuelled UHIs in Tokyo where the average temperature has climbed by 3°C over the last 100 years.

Urban heat islands graph

Temperature differences between rural and urban areas

Cooling canopies

Creating shade in cities, by planting more trees, is an effective method to naturally regulate temperature. An EU-funded study, published in The Lancet medical journal earlier this year, estimated that more than a third of premature deaths attributed to excessive urban heat could be prevented by planting more trees in cities.

The researchers modelled the impact of increasing tree cover in 93 European cities to 30% and found it would prevent 2,644 premature deaths.

When it comes to homes, “Retrofitting with green roofs and green walls is a good way of reducing the UHI effect,” says Wilkinson, whose department is working with other researchers at UTS to test, among other things, the thermal performance of a combination hempcrete wall and green wall construction for housing.

The need for lush greenery is more acute in lower-income communities, which typically have fewer trees and parks and a higher percentage of heat absorbing surfaces, such as roads, buildings and parking lots.

An analysis of 486 metro areas in the US, by conservation organisation American Forests, found that neighbourhoods with a majority of people in poverty have an average 25% less tree canopy than those with a minority of people in poverty.

Penrith City, in Australia, features some of the lowest income neighbourhoods in Greater Sydney and is also one of the hottest living environments in the world. Located in a heat-trapping basin that can be up to 10oC hotter than coastal suburbs, the city hit a staggering 48.9oC in January 2020, making it the hottest place on Earth.

“Some communities living in poorly constructed social housing are subject to appalling conditions, with no air conditioning or shading around their homes,” says Abby Mellick Lopes, an associate professor for design studies at UTS. She is part of the Cooling the Commons project, which explores the capacity of local communities to respond to urban heat and devise appropriate solutions.

Locals in badly designed homes in Penrith have had to resort to DIY workarounds to survive the heat, such as blowing fans over wet sheets draped over doorways or tables to create cool ‘microclimates’ for babies, or makeshift window coverings made from reflecting foil or heavy blankets.

According to Mellick Lopes, long term solutions call for less conservatism in planning and building design to enable “more flexible and agile infrastructures”. She says decision makers can learn from hot cities where the architecture “is far more amenable to cooling”, such as the use of fast-growing vines in southern Europe to create indoor-outdoor living spaces, breezeways and courtyards. High rise buildings in the Middle East and China feature interior stacks capable of “summoning breezes.”

“Retrofitting with green roofs and green walls is a good way of reducing the urban heat island effect” Sara Wilkinson FRICS, University of Technology Sydney

Relationship between surface temperature and vegetation

Slide between the Landsat images of Atlanta, Georgia, US in May 2018 showing the difference between vegetation index and surface temperature

On reflection

When introducing more greenery in urban environments is not viable, another option is to alter the urban fabric itself, choosing surfaces that better manage and mitigate sunlight than dark, impervious surfaces like asphalt or brick.

Campaign group the Smart Surfaces Coalition (SSC) claims a combination of reflective, porous and green surfaces, alongside increasing tree and solar PV coverage can decrease the impact of heat in built-up areas.

Greg Kats, founder and CEO of the SSC, says: “Treating all city surfaces as one integrated strategy to manage sun and rain means far greater cooling potential than just adding trees. Increasing trees can cool a city by one to two degrees, but combining more trees with reflective roofs, roads and parking lots can cool a city by five to seven degrees.”

Several US cities have made progress upgrading buildings and roads to dampen down sweltering temperatures. LA and Phoenix are adding coatings to residential roads to increase reflectivity. New York City’s programme to resurface dark roofs to make them more reflective resulted in as much as 30% reduction in aircon demand on treated buildings.

When Baltimore’s tourism industry was found to be suffering due to excess heat, a city-wide strategy for smart surfaces was adopted. SSC modelled the impact of rolling out 12 cooling measures across the city and found it could cut temperatures in greater Baltimore by 1.7ºC, and in downtown Baltimore by 2.4ºC by 2050.

But such projects in the US remain piecemeal, says Kats, and do not generate the necessary attention or policy support for more ambitious upgrade programmes. Other blockers to progress include a lack of information on the benefits and a focus by transportation officials on lowest cost surface design choices, instead of considering “heat, climate, equity or health.”

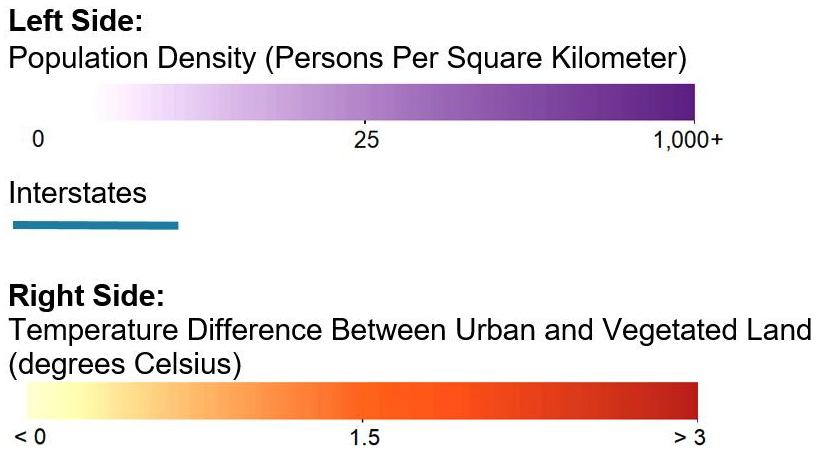

Human impact and the creation of urban heat islands

The map compares population density (left) with the location of urban heat islands (right) globally. The location of urban heat islands map also contains information about the temperature difference between each urban heat island and its surrounding area.

Troubling trajectory

Extreme heat is a depressing reality for cities near the equator, but even municipalities in historically cooler latitudes are now having to adapt for sweltering temperatures.

When thermometers hit 38.5°C in England back in 2003, it caused 2,193 heat-related deaths in just 10 days. But heatwaves this severe could occur every other year by the 2040s, according to forecasts by the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee.

UK-based built environment health and wellbeing consultancy Ekkist has developed a Design for Wellbeing Framework that addresses overheating issues as part of a holistic approach to creating healthy environments.

According to Olga Turner Baker MRICS, managing director at Ekkist, effective housing design strategies should consider building orientation to reduce solar gain while maximising daylight, using manual or automated exterior shading devices.

“Studies have shown that green façades can support the reduction of cooling load and local temperatures by as much as 10ºC, with the added benefit of reducing local concentrations of particulate matter by between 10-20%,” she says.

In addition, better insulated buildings can help keep heat out. Passivhaus standards include a summer overheating criterion to ensure internal temperatures do not exceed 25ºC for more than 10% of the year.

Most projects tackling urban heat in the UK tend to be at asset level and cities lack a joined-up strategy. One initiative that looked at things differently was the EU-funded Ignition project in Manchester. It worked with partners (including businesses, local authorities, landowners and communities) to develop innovative ways to finance nature-based solutions that provide resilience against extreme climate hazards, including urban heat.

Research carried out under the project demonstrated that solutions like rain gardens, street trees, green roofs and walls and urban green spaces could help mitigate UHIs and create temperatures comfortable to live and work in.

Municipalities like Manchester that are proactive on the issue of urban heat will be better placed to ensure resilience in the future, according to Hannah Giddings, senior advisor for resilience and nature at the UK Green Building Council.

“A lot of people see this as a future problem we don't really need to address today,” says Giddings. “But if events like the 2022 heatwave in England happen more often, with higher maximum temperatures, it's going to get to the point where lots of people are impacted. Starting to understand the risks today and planning and preparing for them is something we should definitely be doing.”

“Studies have shown that green façades can support the reduction of cooling load and local temperatures by as much as 10ºC” Olga Turner Baker MRICS, Ekkist