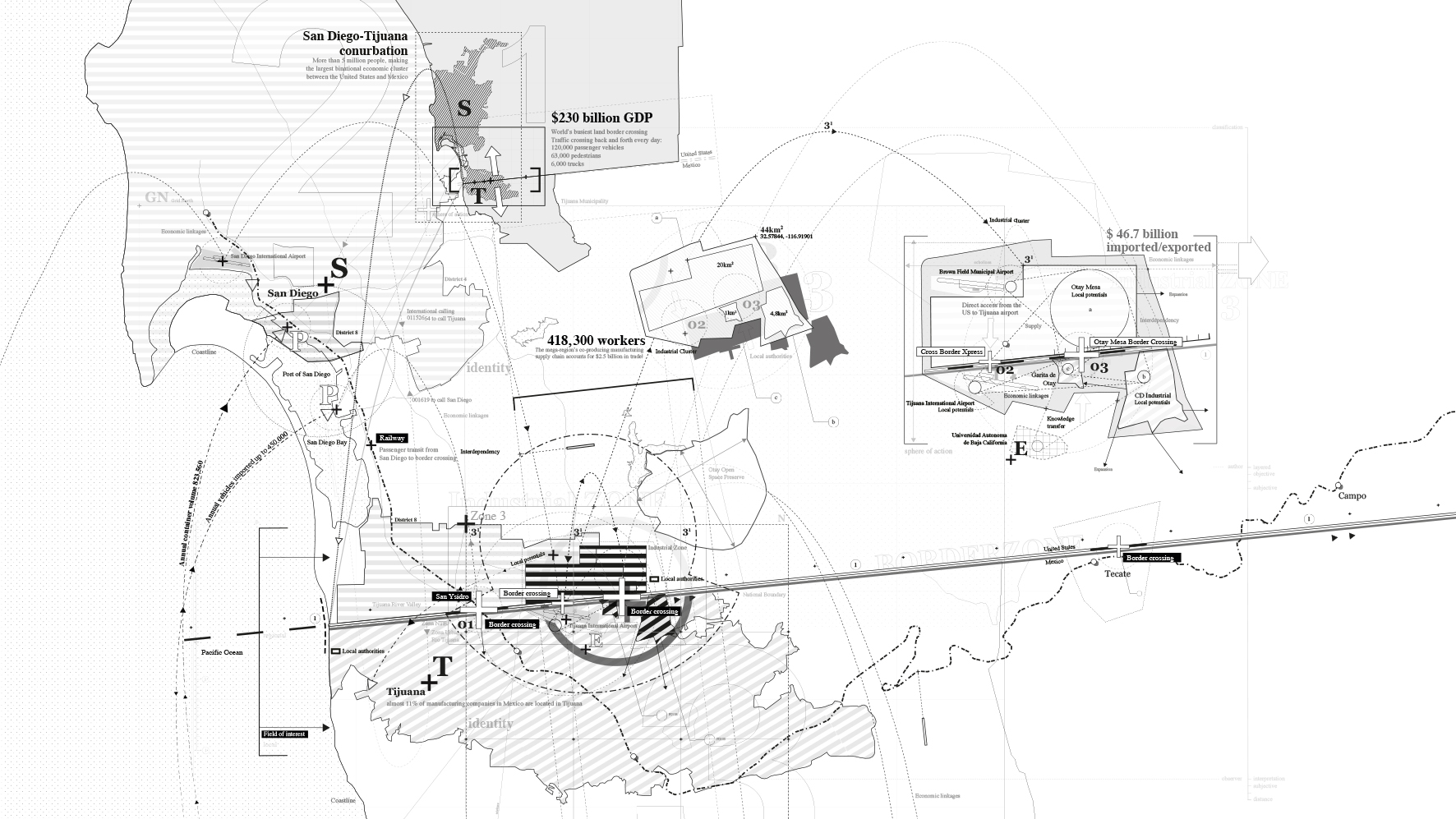

San Diego-Tijuana megaregion. Illustration by Alexander Daxböck

The established market: San Diego-Tijuana

Every day, some 120,000 passenger vehicles, 6,000 trucks and 63,000 pedestrians cross back and forth between San Diego in California and Tijuana in Mexico. It is the world's busiest land-border crossing and one of the continent's most significant binational economic clusters, with a GDP of $230bn and a population of more than five million people split across both municipalities.

In the gravity model of trade, the San Diego-Tijuana megaregion is something of an inevitability: two large economic centres in close proximity to each other tend to be strongly tied. In addition, deep cultural links – about 25% of San Diegans are native or fluent Spanish speakers – have helped to ensure a steady migration of labour and skills. But it was 1994's North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) that accelerated the commercialisation of the megaregion, particularly its specialisation in advanced manufacturing.

Today, Tijuana is home to the world's largest medical device cluster. It also hosts Mexico's aerospace, defence, semiconductor and audio and video equipment manufacturinG industries. Many of these firms – such as Solar Turbines, Kyocera International and Taylor Guitars – are co-located on both sides of the border, with their administrative and operations facilities in the US. In San Diego, where 8.5% of the workforce is concentrated in STEM-specific occupations (more than 1.5 times the US average), biotechnology, pharmaceutical, software and communications clusters provide R&D that drives innovation, effectively "offshoring" production to Mexico.

NAFTA enabled both San Diego and Tijuana to benefit from the competitive advantage that comes with being "co-producers", fuelling huge growth in support and ancillary businesses. Integrated supply chains mean that a medical device or automobile may cross the border many times before it is finished. What's more, this trade in intermediate inputs means that 40% of US imports from Mexico are actually "American-made". Research by World Trade Center San Diego estimates the value of this co-producing manufacturing supply chain at $2.5bn.

"Because of this, San Diego-Tijuana is really driving the whole of the Cali Baja megaregion [which includes San Diego County, Imperial County in the US, and the State of Baja California in Mexico]," says Max Bouchet, research analyst at the Brookings Institution.

Bouchet, who has conducted research on the international relations of cities, says that the megaregion challenges the US government's protectionist narrative of "win-lose trade relations'. The US economy is heavily reliant on imports to supply US producers with the materials and parts they need. The binational economy of Cali Baja is a good example of this interdependency."

Tim Gifford FRICS, senior managing director, capital advisers for Latin America at CBRE, says that the US- China trade war is actually one of the reasons demand is going up in the region: "We're seeing more and more demand for industrial space in Mexico for manufacturing and logistics. Lots of it is organic. But more integration between the US and Mexico is inevitable because it's easier than China – lots of businesses operating in these areas are coming to the conclusion that there's less risk of those networks becoming disrupted."

Gifford believes that Trump's proposed border wall, if it is realised, will have little effect on the regular flow of business between San Diego and Tijuana. In fact, the region already has an entry point that literally crosses above the border fence: the Cross Border Xpress. Funded by private American and Mexican investors, this 390ft footbridge opened in 2015 and connects Tijuana International Airport to a terminal on the US side of the border. A third vehicle crossing point is also due to be completed this year at Otay Mesa East. Both the public and private sector seem to think binational infrastructure projects will pay off in the future.

Despite rising US-Mexico tensions, the renegotiated NAFTA – now the United States-Mexico-Canada-Agreement (USMCA) – may benefit San Diego-Tijuana as its services sector evolves. Some 51% of trade in the Cali Baja megaregion is in the services sector, from software to data processing and scientific research, an important aspect of which is R&D patents. "USMCA modernises NAFTA, in particular on data and IP protection. Both sides were looking at this," says Bouchet.

And if the trade war continues? Bouchet believes that being a binational region should position San Diego-Tijuana to be more resilient, "allowing it to access more competitive markets and provide flexibility for firms on both sides of the border to find ways to mitigate the effects of [retaliatory] tariffs."

The emergent force: China's Greater Bay Area

Plans for China's Greater Bay Area (GBA) were mooted as early as 2005 as part of the Pearl River Delta concept. It faltered again in 2011 due to a lack of coordination between the large number of regions and cities involved. But in 2017, the People's Republic of China stepped in: "The government sees that forming a huge area here would create a market and the capacity for innovation. Now, we have a central planning function over the whole area," says Clement Lau FRICS, director and head of development and valuations, commercial property, at Hongkong Land.

The plan is for the GBA, which will link nine mainland cities in Guangdong province, as well as the two Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau, to be a globally competitive megaregion by 2035. The core cities of Hong Kong, Macau, Guangzhou and Shenzhen will be "productivity clusters", which the others, Zhuhai, Foshan, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen and Zhaoqing, will support by specialising in high-value-added manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, energy and other industries. "The beauty of this integration is that one plus one no longer equals two; but two and a half or three," says Lau of the potential spillover effects.

With a combined urban population across 11 cities of 54 million – the UN forecasts a 30% increase between 2015-2035 to almost 70 million – the GBA dwarfs the US's Northeast Corridor and the San Francisco Bay Area. As part of China's Belt and Road initiative, the GBA is intended to serve not just an internal market but also neighbouring countries, and to compete with these megaregions: the high-tech cluster at Shenzhen with Silicon Valley, for example.

As Lau explains, the GBA differs from the traditional Chinese model: it will be the private sector that will come up with the ideas and business policies; government will invest in the infrastructure projects, such as the Nansha Bridge, which opened in April 2019, that will provide the high-speed connective tissue. It will also have to balance the differences in the currency, tax, legal and financial systems in the cities. "The first thing the government is trying to do is enable the free movement of capital, information and talent in the region," says Lau.

Research published by RICS and Colliers International in a September 2019 report, Greater Bay Area: A 2030 Outlook, found that an additional 21m m2 (226m ft2) of office space could be needed by 2028 given the GBA's forecasted economic growth. And as infrastructure improves, activity that crosses administrative boundaries becomes more possible: 14% of Hong Kong occupiers indicated that they would like to expand into the other GBA cities. Given the relative high rents in Hong Kong, emerging office markets across the border could serve as more affordable alternatives to Hong Kong for incubators and start-up companies.

The close proximity of the GBA cities means travel times between them are already lower it takes less than an hour to travel between Hong Kong and Guangzhou, compared with more than three hours between New York and Washington, for example. But it's more expensive than travelling within your own city, so the next step is to bring down the cost.

The biggest challenge, however, is attracting and retaining talent. "The skills gap among different cities in the GBA is big, with talent concentrated in the core cities. This can lead to unbalanced development," says Alva To MRICS, vice-president and head of consulting, Greater China, at Cushman & Wakefield. He adds that progress is being made in the "demonstration zones" of the GBA, notably Qianhai, Hengqin and Nansha. "These new areas adopt special policies that are not enforced in the rest of China. For example, in tax and currency, or with incentives to attract talent such as special housing programmes."

Hong Kong citizens working in the GBA get a rebate for local tax so that their tax position, which is more favourable in their home city, stays the same on balance. There are also discounted office rents for companies in the innovation and technology sectors, or restrictive terms in the sales of properties that ensure real estate is for industrial development instead of speculation.

Making the GBA as attractive as, say, Silicon Valley, New York or London for high-skilled talent is something the government is "very conscious" of, says Lau. Without it, the megaregion faces a considerable challenge.

"The biggest challenge, however, is attracting and retaining talent"

The embryonic plan: Scandinavia's String Partnership

Scandinavian cities tend to have small, dispersed populations. Notable concentrations are only found around the four metropolitan areas of Oslo, Gothenburg, Copenhagen/Malmö and Stockholm. Since the Øresund Bridge opened in 2000, linking the Danish capital with the Swedish port city of Malmö, a small number of projects have emerged making the case for how the success of the cross-border crossing could be extended on a Scandinavian scale.

"The lesson we learned from Øresund is that physical infrastructure – in this case the bridge – forms the basis for integrationt; says architect Floire Nathanael Daub, partner at Oslo-based Spacegroup. Until 2014, Daub led a three-year EU-funded project called the Scandinavian 8 Million City: a high-speed train link that would connect Oslo with Copenhagen via Gothenburg and Malmö, cutting the journey from eight hours to two-and -a-half, and creating a cross-border labour market of 8 million people, 29 universities and an additional 44,000 companies every year, based on Spacegroup's analysis.

The goal was to mirror the cross-border planning approach used for the Øresund Bridge to obtain a collective agreement from the Scandinavian governments for the financing and development of 600km (373 miles) of double-track railway for intercity and high-speed trains on the Oslo-Gothenburg-Copenhagen route by 2014. When this was eventually derailed – by local resistance to the cost and the location of the line, says Daub – Spacegroup initiated a roundtable of private and public companies to see if a business case could be made without depending on state funding.

Model forecasts, carried out by Atkins on behalf of 8 Million City, showed that high-speed rail in Scandinavia could be carrying 9.4 million passengers a year by 2024, comparable to the 9.7 million that Eurostar carries between Paris and London. "The Oslo-Copenhagen passage is not just important for the residents and companies – it also functions as an important gateway to and from Europe for the rest of Scandinavia," says Daub. For example, most goods transported by land in Norway go via this route, and one-third of Swedish foreign trade passes through Gothenburg port. Analysis by 8 Million City showed that pathways for goods trains have already reached maximum capacity, as have – in places – the region's motorways.

Daub says: "If Scandinavia is to continue to develop, while also achieving its climate goals, we must create the conditions for green alternatives to passenger and freight transport." However, he says the 8 Million City's biggest challenge was always "aligning political interest across national borders and [making the respective governments] allocate the budgets needed to implement the project." Unfortunately, no such agreements had been negotiated by the time the funding expired, and the project ended in 2016.

Enter the String Partnership. Originally a lobby group for the Fehmarn Belt Link – a road and rail tunnel that will connect Germany with Denmark under the Baltic Sea – String, which has 13 members made up of mostly city and regional government bodies, has now turned its attention to regional development and green growth.

Building on 8 Million City's work, it has expanded the high-speed rail corridor to include Hamburg, creating a potential megaregion of 12.6 million people, and doubled down on the narrative around green growth. "We asked our members: what do you want to do with this connectivity?" says String's managing director, Thomas Becker. "We want to define what we are going to live off in the future, when the old industries are disappearing."

With a disproportionate number of green industries and engineering talent in Europe based in this region – from world-leading solar cell manufacturers in Norway to powerhouses such as Volvo, which is now only producing hybrid and electric cars – String created a new strategy: to become the green industrial hub of Europe.

Although vague attempts to do the same have been made in the Netherlands and Belgium, Becker says its main competitor is Singapore, "which has invested heavily to be able to make this claim." Nevertheless, he believes the String corridor has a competitive advantage: people in the region tend to be well educated, it has a high GDP and there are few cultural differences between the countries. Now it needs the infrastructure.

String has signed an agreement with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to conduct a costly mapping project of the strengths and weaknesses of all the regions involved. The report will provide a set of actions that need to be met for the project to achieve its goal. "This is not a done deal," says Becker. "You need governments to make a treaty at a national level for the String area to become a green investment hub. But it would be a pity to miss this opportunity."

RICS' World Built Environment Forum discusses global themes.

Images © Getty

"If Scandinavia is to continue to develop, while also achieving its climate goals, we must create the conditions for green alternatives to passenger and freight transport"