Two years ago, a leading public figure set out his thoughts on the way companies should behave. “To prosper over time, every company must not only deliver financial performance, but also show how it makes a positive contribution to society,” he wrote. “Companies must benefit all of their stakeholders, including shareholders, employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate.”

These were not the words of then Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn – or any politician for that matter. They were the words of Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, in his annual letter to the chief executives of the companies in which BlackRock is invested. His message was clear: get yourselves an effective environment, social and governance (ESG) strategy or we’re off. Given that BlackRock at the time had $1.7tr under management, Fink’s words carried real weight.

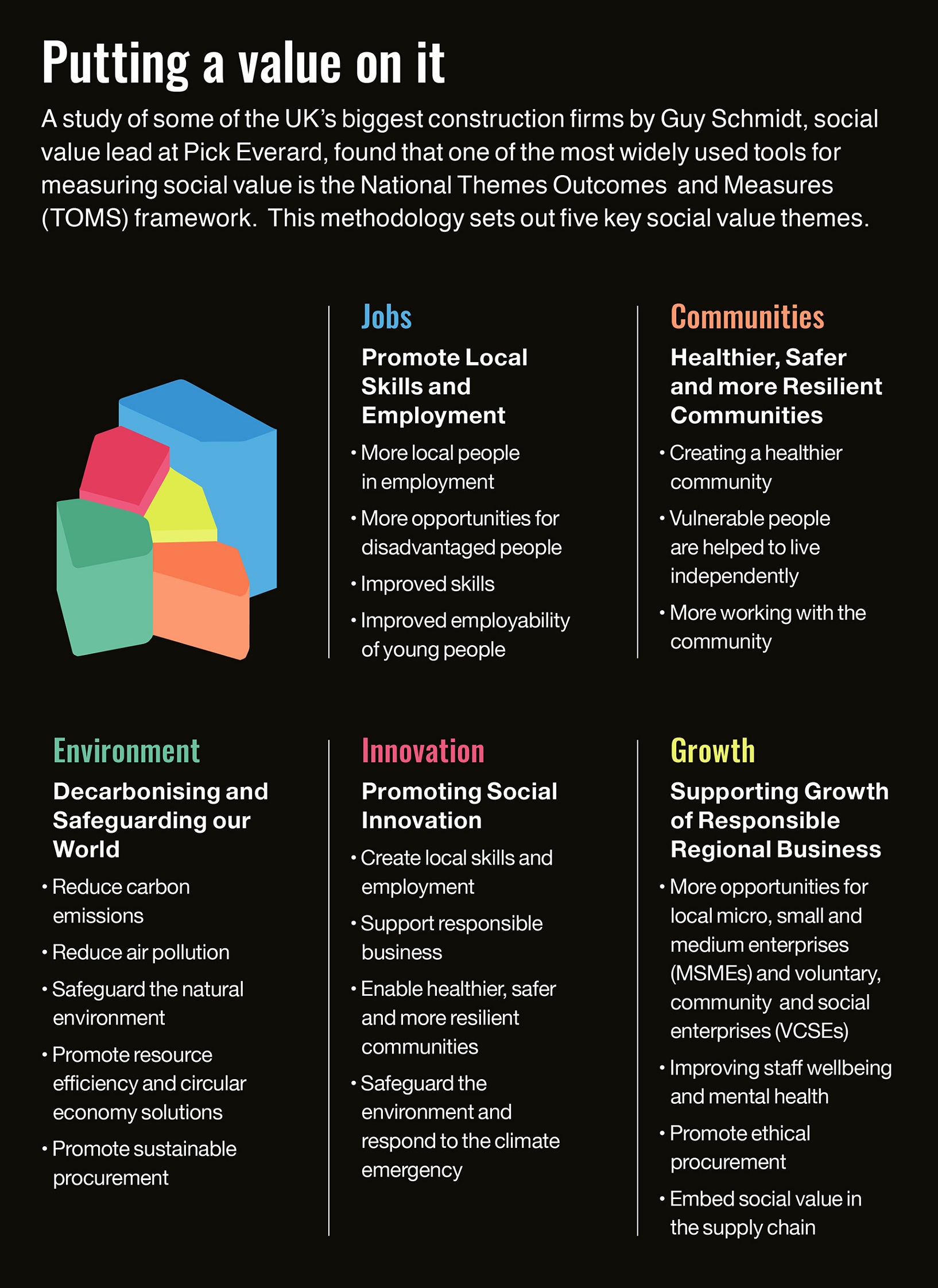

Of course, what can be achieved in terms of social value will be different depending on the industry in which an organisation operates. In the built environment, the very things the industry creates – buildings, infrastructure – have a direct and tangible impact on people’s everyday lives. So what social value can the built environment generate? And how can it be maximised?

Small changes, big impact

In the US, it has been recognised at a federal level for some time that there is the potential for relatively small investments in real estate to lead to substantial economic development and community benefit. That was the principle behind the establishment of the National Trust Community Investment Corporation (NTCIC), a for-profit subsidiary of the not-for-profit and privately funded National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Before setting up his own organisation, District Honor LLC, Joseph Crugnale worked for the NTCIC assessing projects for investment. He says it was critical that chosen projects would have a genuine impact. “There are several ways to measure that,” he says. “One of the first things we do is look at the needs of a community. I would look at the demographics of a community and pull up data on poverty rates, unemployment, median incomes and so on.”

However, Crugnale adds that he would also ask communities themselves whether they had identified any local priorities. “If we were looking at investing in a project in Baltimore, for instance, we’d look at whether it has any sort of economic development or community plans where they outline needs for different neighbourhoods,” he says. “From our perspective as a national organisation, we didn’t know the peculiarities of different markets so we really had to understand what a community needs in order to provide investments that will meet those needs.”

Beyond job numbers

The next stage is to understand what type of asset and project proposal can best target local need. Say there are two potential projects in a neighbourhood with a high unemployment rate. One of them might be an office facility that’s projected to create 100 jobs and the other an industrial facility that’s going to create 30 jobs. On the face of it the office might seem like the better option.

“But when you start looking at it you realise that the office project is targeting tech tenants, and they will probably hire people with college degrees and specific skill sets,” says Crugnale. “The manufacturing facility doesn’t have those educational requirements, so if it’s a low income community the chances are that the second project is going to have a bigger impact. So, we tried to look at nuances of projects and make sure they align with the needs of a community.”

Matt Stavrou, socio-economic lead at JLL in the UK, agrees that looking beyond the basic numbers in terms of jobs created and gross value added (GVA) is important. “It is all about the impact that you have created, so how you have changed people’s lives,” he says. “It’s less about the simplified numbers and more about who gets the jobs, the quality of the jobs, whether you’re employing people who were previously unemployed, the skills and so on. You should probably do both, but JLL is largely of the opinion that the impact on people’s lives is the most important thing to measure.”

One example of NTCIC’s work in action can be found in Owosso, Michigan, a small town of fewer than 20,000 people. Like a lot of places in the Mid-West it has been hit by deindustrialisation, population loss and an ageing population. “Its small nature means that it’s not a magnet for investment, but they had this old armoury on the edge of the downtown that had been vacant for around 10 years when [in 2017] the local chamber of commerce started putting together a project to turn it into flex office space,” says Crugnale.

"It's more about who gets the jobs and the quality of jobs"

The proposed project included everything from individual desks to co-working spaces to flexible offices for multiple people. The idea was that they wanted to provide a venue for people in the community who were perhaps commuting to big cities a few days a week, or just a cool venue for people in the local area.

“It was about bringing activity back to the downtown,” says Crugnale. “We provided an investment and it was a really big deal. It had full community support and the mayor and local organisations were all on board. It provided a shot of confidence for this community, which was trying to find its footing again. To have that reactivated provided a big boost to the community. It’s acted as a catalyst – other developments are now happening around it.”

However, such work does not need to be led by spin-offs from not-for-profit organisations. Phil Higham FRICS, director of consultant Realworth, advises developers and public bodies on how they can secure the greatest social benefits from development. Typically, he works on large urban regeneration projects and says the benefits that can result are many and varied, including reduced crime rates, improved community cohesion and, crucially, job creation.

“Employment and training is common because a lot of the places that we help developers and authorities create also create new jobs,” says Higham. “There is a great deal of social value arising from that, especially if the employment that is created is targeted at overlooked groups. We encourage our clients to think about partnering with voluntary or social organisations in the vicinity and help them establish their training and development programmes. If we can connect the people doing the development to vulnerable people in the area, that’s where we see the biggest impact.”

Better for the bottom line

Encouragingly, Higham says that developers are increasingly interested in how their projects can secure as much of a social return as possible and are thinking about it early on. “Developers are more switched on and the more progressive ones can see that better social and environmental design and delivery actually provides a better return for everybody, including on financial terms,” he says.

For instance, Realworth is currently working for developer U+I on its vast Mayfield scheme in Manchester. The project was subject to a competition run by the city council, which included social value requirements in the bid documents for companies seeking to be appointed as preferred developer. “We were brought onto that scheme in 2015 and U+I asked us to help them respond to the social value requirements,” says Higham.

“We did a study that helped them to understand the prevailing need in terms of social economic data. In that particular area there was a high rate of crime because there was a lot of dereliction around the site. There was also a risk of segregating a neighbouring community. We helped them reinforce their thinking about permeability. Manchester has also suffered from a lack of green space, so a big element of the project is a park and we helped them to strengthen the business case.”

However, Karl Limbert, integrated solutions director at Engie UK, is not convinced that the way in which councils include social value requirements in procurement documents is always particularly effective. “It doesn’t have the right gravity – I don’t think I’ve ever seen social value in a tender document account for more than 5% of the marks,” he says.

“What happens is there is a fairly involved conversation between client and bidder and lots of ideas are worked up. And then that fizzles away into this big spreadsheet that isn’t really worth the bother because it is never going to make the difference between winner and loser. I think people would be prepared to put more risk into it. I think the private sector thinks it could do better.”

Of course, such early work does not necessarily translate into results, and Higham says there can be issues when responsibility passes from commissioning to delivery in a local authority. However, he adds that increasingly, developers are willing to be held to account. Famously, Argent commissioned an independent study of the social impact of its work on the regeneration of King’s Cross after the first 10 years of the development.

Long-term accountability

At Mayfield, U+I is taking it to the next stage by commissioning annual impact reports from Realworth. “We’ve already done our first annual report on Mayfield and there is a commitment from U+I to continue to monitor and track the social value that has been created,” says Higham. “If we haven’t created the value we expected, what are we doing wrong and what can we do to fix it? People who take that approach are going to have the credibility with commissioners. In the past, there weren’t enough people who were willing to stand up and be counted.”

The built environment’s contribution to social value isn’t limited to buildings – infrastructure projects too can lead to huge benefits to multiple communities. “The social value of an infrastructure project is the net value generated to society,” says Anil Sawhney FRICS, director of the infrastructure sector at RICS. “This includes impacts on the infrastructure industry itself, such as benefits to businesses and employees, as well as benefits to wider society.”

In recent years there has been a marked increase in built environment professionals taking a genuine interest in the social value that can be derived from their work. However, there are also fears that the Covid-19 crisis could result in people losing focus and seeking only to shore up the bottom line. After all, in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, much of the momentum that had built up on the environmental sustainability front was lost.

Georgina Dowling, director and head of environmental planning and assessment at CBRE UK, doesn’t think the same will be true for social value. “I don’t think it will fall by the wayside because I think the nature of what is happening at the moment and the fact that we’re all in it together is a lot of what social value is all about,” she says.

“If you look at how we’re mobilising to support the NHS [see box opposite] and give them the equipment they need, that is a good indication of social value operating. There are always going to be operators that only have an eye on profit, but I think it’s very hard now to not have a social conscience. That will be heavily scrutinised after this. People are so much more aware of social responsibility.”