_14%20Dec.jpg)

From left to right: Michaela Bygrave MRICS, Thuso Selelo MRICS, Kiabi Carson and Ally Reid MRICS

Like many sectors, the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020 forced firms working in the built environment to reflect on their hiring practices and company cultures, and whether they exclude black professionals.

As the year draws to a close, and the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic sucks up company time and resources, it’s more crucial than ever to sustain the momentum behind this conversation.

For its part, RICS announced in August that it was focusing its efforts on four areas. First, it will strive to better highlight the diversity of the profession in conference panels and is working to identify technical experts that wish to speak at events and conferences and match them with appropriate opportunities.

Attracting the next generation of talent

Barry Cullen, diversity analyst at RICS, is optimistic that businesses are acting on the problem of racism and discrimination in the sector. “Black Lives Matter shone a light on businesses that weren't on this journey, which suddenly realised they’d better be – and that they aren’t going to attract the next generation of talent if they are perceived as part of the problem rather than solution,” he says.

Independent consultant Michaela Bygrave MRICS takes a more cautious view: “We’ll have to wait and see who, in five years, is getting promoted and who is staying on at their firms rather than branching out on their own.” She is one of those who did just that – in 2018 she founded Pointe Michel, a real estate consultancy firm that prioritises social responsibility, after eight years in employment.

Reflecting on her own experiences and those of black colleagues, she says the cultural homogeneity of the sector stands in the way of progress for many people. “A lot of firms need to be dismantled and rebuilt from the ground up, because there’s a real guardianship surrounding surveying – many people think that certain people belong and ridicule those they think don’t. There’s always pressure to conform. Firms need to look at their culture, in terms of how you make people who are not white, heterosexual or middle class feel comfortable.” Since setting up on her own, she has observed that very few of these expectations come from clients. “I’ve never had any pushback over the fact that I'm a working-class black woman, who wasn’t privately educated.”

Thuso Selelo MRICS is assistant head of valuation and strategic assets at the London Borough of Lambeth and recently left his role as associate, development and valuation at Montagu Evans. In his experience, the public sector tends to be a much more inclusive environment for black professionals than private firms – speculating that it’s related to a more transparent recruitment process. “Experience shows that there is a tendency in the private sector to recruit graduates from a similar background and from the same universities, thereby excluding a wide range of graduates from other universities,” he suggests. “This unconscious bias inadvertently leads to a lack of recruitment of black graduates.

_14%20Dec.jpg)

His own experiences have convinced him not to recommend a career in surveying to his own son, who is in the process of applying to university. “While it is not easy to explain our profession compared to engineering, law or nursing, I am less likely to recommend a career in property to my son due to the perceived lack of equal opportunities at graduate level,” he says. These comments illustrate quite neatly that, to change the mix of the industry, interventions need to start early, with outreach to schools to encourage a diverse range of people to look at property as a career, followed by real change to ensure equality of career prospects.

Inspiring and educating youngsters

Changing the Face of Property is a UK-based alliance between such big names as CBRE, Cushman & Wakefield, JLL, Savills and BNP Paribas Real Estate, which is striving to promote industry diversity. “The candidate pool for recruitment is currently not representative of the UK population,” says one of its members, suggesting that businesses should be more active in offering work experience to school children.

“It is also important to ensure more people enter university from a variety of backgrounds, and that we educate students about the different options available to them.” They add: “Businesses need to take it upon themselves to collectively offer candidates from different socio-economic and ethnic minority backgrounds the chance to engage with, and understand, the industry and the opportunities it offers.”

_14%20Dec.jpg)

In the US, the epicentre of this year’s Black Lives Matter movement, many companies made public statements about the killing of George Floyd, and taking actions such as introducing diversity- and inclusion-awareness training and rethinking hiring practices. Kiabi Carson, head of human resources at Turner & Townsend North America points to the introduction of its “PlainSpeak” roundtable discussions as a way of opening up debate around the subject of racial justice in the US, which is often treated as taboo in the workplace.

“We felt it vitally important that our employees had a place where they felt supported in expressing their concerns, frustrations and fears while learning from each other,” she says. “Based on the overwhelmingly positive feedback we got in response, we were right.”

It’s time, says Carson, that diversity and inclusion stopped being treated as a side issue. “It should be treated the same as you would any other business issue that is impacting the performance of your business, with the same level of rigour, monitoring and accountability,” she says. “Whether your business is doing well or not, a lack of diversity impedes your full performance potential. The market is changing. Our society is demanding that businesses demonstrate and act in alignment with a social purpose.”

In recent years RICS has made a specific effort to increase the number of chartered female surveyors, through a mix of increasing women’s visibility on panels and in the stories the organisation highlights, as well as engaging young women at school age. Although the number is still only 16%, Cullen says the strategy has yielded results, so there is little reason that a similar approach could not work when striving to increase ethnic diversity. “Since 2015, we have aimed to raise the number of women coming into the profession by 1% a year, and we have achieved that for the past five,” Cullen says. “We’ve seen a 93% increase in the number of women enrolling as surveyors over five years.”

Carson says recruitment targeted at underrepresented groups is vital to improve diversity, for example by advertising at colleges and universities with a greater proportion of black students and liaising with community groups to offer mentorships to students whom the sector would otherwise ignore. “We need to start earlier in the pipeline to attract more black or African American people into our industry – starting at high school and university levels,” she says.

Then, in the early stages of a career, all young surveyors need inspiring mentors to guide them and help them gain experience. Bygrave is taking an active approach to make sure that, when it comes to recruitment, she has a choice of qualified surveyors of all races. “I am mentoring younger surveyors from underrepresented groups, because I want to make sure they are at the level they need to be to compete for jobs,” she says. “I say to all black surveyors, if you care about this issue, then it is your responsibility to make sure other black surveyors coming after you have a better time.”

De facto diversity officers

Nonetheless, she sounds a warning about demanding that black professionals solve the problem of racism. “There has been a lot of pressure on black professionals this year to offer solutions.” she says. “I know a few people who have day jobs who, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, have been made de facto diversity officers, without extra pay, just because they’re black.”

_14%20Dec.jpg)

Ally Reid MRICS, an investment manager at LandSec and chair of its ethnic minority network, argues that the responsibility for mentoring a diverse new generation of surveyors should be spread evenly. “It doesn’t seem fair if ethnic minorities have to mentor each other,” she says. “I think we should be interacting across demographics to unlock the benefits of diversity. If we acknowledge how hard it is for minorities to get into those positions of seniority in the first place, it is counterproductive to increase their workload.”

Like Bygrave, Reid has also seen black professionals deciding to make their own way, rather than remaining in employment. “I keep seeing them on the periphery of their industry, creating their own consultancies to get ahead, rather than reaching senior roles in organisations because they keep hitting a glass ceiling and there is no one putting their hands down to pull them up, so to speak.” She points to the need for better statistics on representation and the distribution of staff from minority groups across businesses. “You can't improve what you don’t measure.”

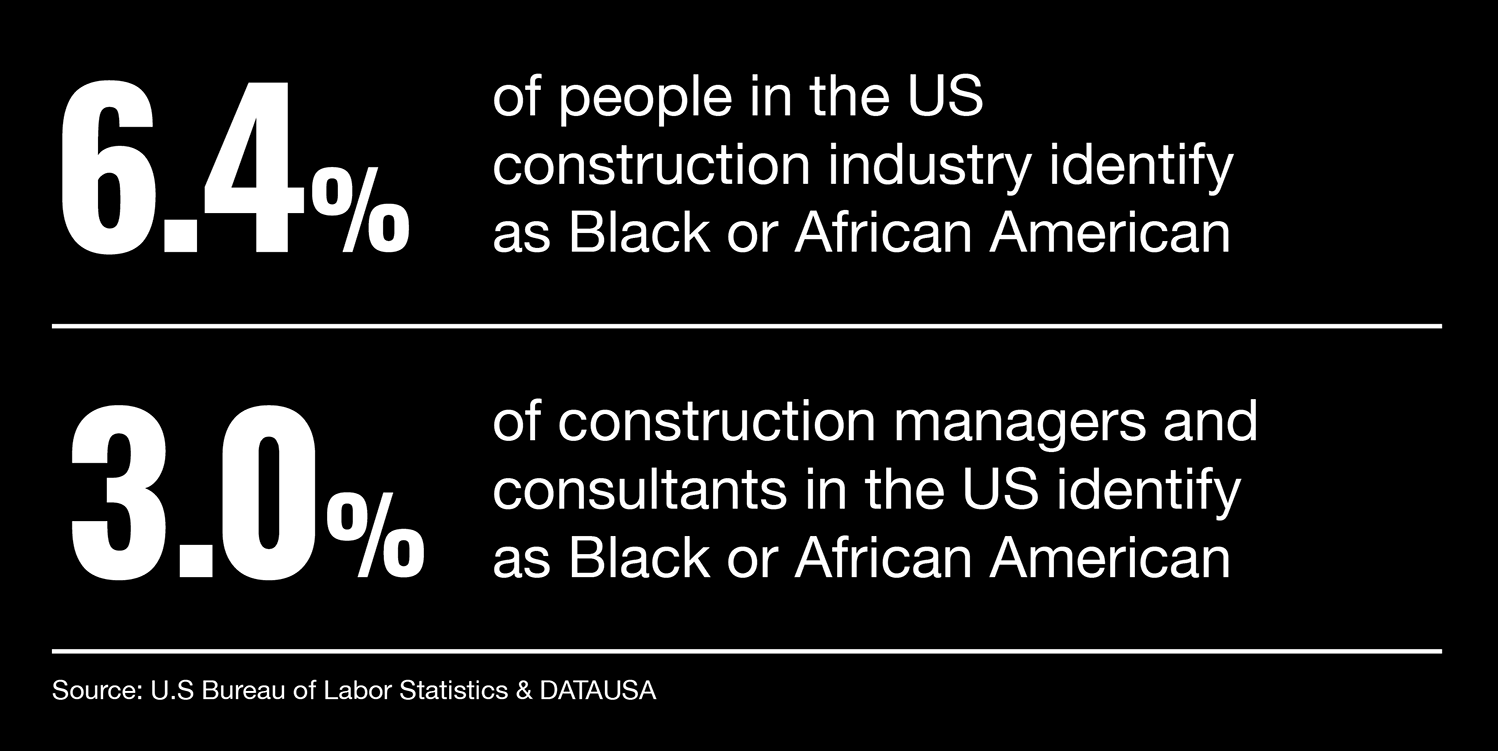

In the US, the numbers also show there is less ethnic diversity the higher you go up the ladder: 6.4% of the construction industry identifies as black or African American, but that shrinks to about 3% when you look at construction management and consultancy. A report in 2019 showed that only 4% of men and 2% of women at executive levels were Asian or African American.

Last year, several businesses, including CBRE, Cushman & Wakefield and Mott MacDonald, started reporting their ethnicity pay gap alongside their gender pay gap, which has been obligatory since 2017 – the firms above revealed gaps varying from 10% to 25%. Cullen says that these numbers – and the statistic that 1.6% of RICS professionals in the UK are from ethnic minority backgrounds – are skewed by the fact that few people opt to disclose their ethnicity when asked.

Moreover, most of these pay gap reports make a sweeping comparison between white staff on one hand and all non-white staff on the other, which erases the variation of experiences between people from different ethnic backgrounds – and, in doing so, fails to home in on the specific concerns of black professionals. RICS is encouraging firms to gather more detailed data on ethnicity for their pay gap reports in future.

The mandating of gender pay gap reporting has already started to have an effect. In 2019, for example, Montagu Evans committed to 50% of its graduate intake being female. For Selelo, this is strong evidence that making things compulsory works.

“It would make a big difference and deliver long-term benefits, in the way that gender pay gap reporting has led to the promotion of qualified and deserving female partners/directors,” he says. Making this information public would also create scope for public procurement to take this into account when commissioning work. “If it’s money-driven, firms would be forced into action.”

Numbers can, however, only take you so far without cultural change. Reid reminds us that goals related to ethical matters such as sustainability and diversity do not necessarily give you immediate financial returns, so there can be pushback at first when embedding them into business practice. “Whenever you're trying to change a culture you are going to meet some resistance,” she says. “You have to include those you are bringing with you in the story.”

Cullen believes there is hope on the horizon. At the moment, he says, 12% of apprentices are from black, Asian, minority ethnic (BAME) communities. This is compared with 14% of the working population, which is better than representation higher up the ranks. He points to initiatives such as five-year apprenticeships that allow you to earn as you learn, and qualify with no student debt, as strategies that could encourage a wider pool of applicants. He adds that there are signs of more joined-up thinking among businesses when it comes to promoting the profession to future recruits.

Together these measures contain the possibility of change, but this relies on the sector embracing them with genuine intent. As Selelo says: “If you remove those barriers to entry for young professionals, then in four years, you can change the makeup of the industry.”