It is hard to calculate the impact that a wildfire can have on the environment it burns through: beyond the damage and danger of the immediate conflagration is the time that the scorched earth will take to recover. As fires grow ever more intense, returning the land that has been ravaged to its former use is becoming more challenging.

Global fire statistics

Research by Stephen Pyne, an environmental historian at Arizona State University, shows a decades-long, growing trend of wildfires lasting longer than they did even a few years ago. He cites data that put the average duration of a fire that took hold between 1973 and 1982 at six days. But that figure soared to 52 days between 2003 and 2012. "So long as there is fuel and it doesn’t rain or snow, a fire can burn, and burn, and burn," Pyne says.

Eight of the 10 longest-lasting fires have taken place in Australia over the period from 2004-15. The worst set of fires took place in 2006 and were the result of lightning strikes in Victoria, Australia during which dozens of separate blazes were ignited and later converged. Despite consuming about 1.3m hectares, injuries were minimal and there were no deaths. By comparison, the fires that took hold of neighbouring New South Wales during 2019-20, spread across 5.5m hectares and were responsible for 26 fatalities.

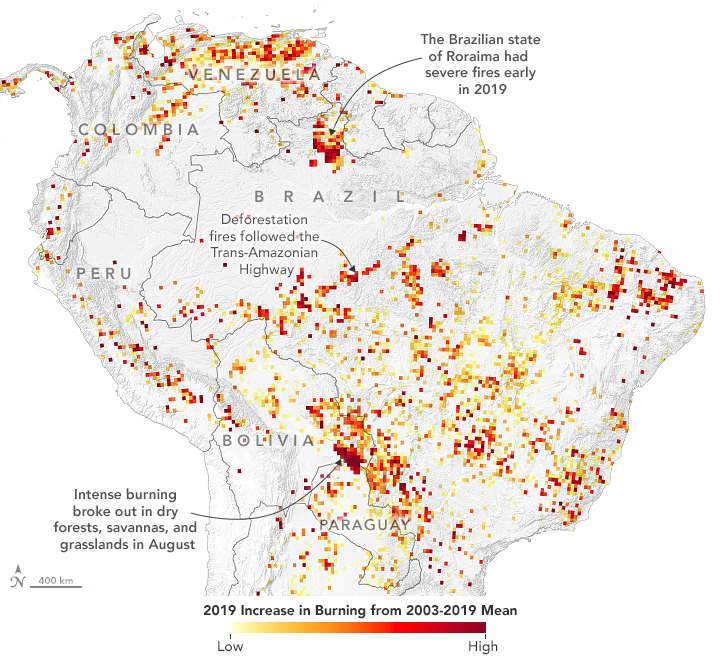

Tree cover loss due to wildfires was particularly bad during 2013, as fires blazed through Russia and Canada consuming more than 6m hectares of woodland across the two countries. Although wildfires are traditionally associated with forests, they can also engulf areas with much less vegetation such as grass or prairie land and even moors or tundra. In Brazil, the number of trees lost to wildfires appears to be low. But this is because the dominant cause of tree loss there is deforestation, for purposes such as mining and cattle grazing.

Air quality

The graph shows the emissions levels caused by wildfires in some of the countries that experience regular fires. Although Brazil, for example, experienced spikes in the 2000s, most countries have had their air quality more profoundly affected by wildfires in the past five years, and four of the five have seen a sharp increase in emissions during 2019, the final year for which there is data.

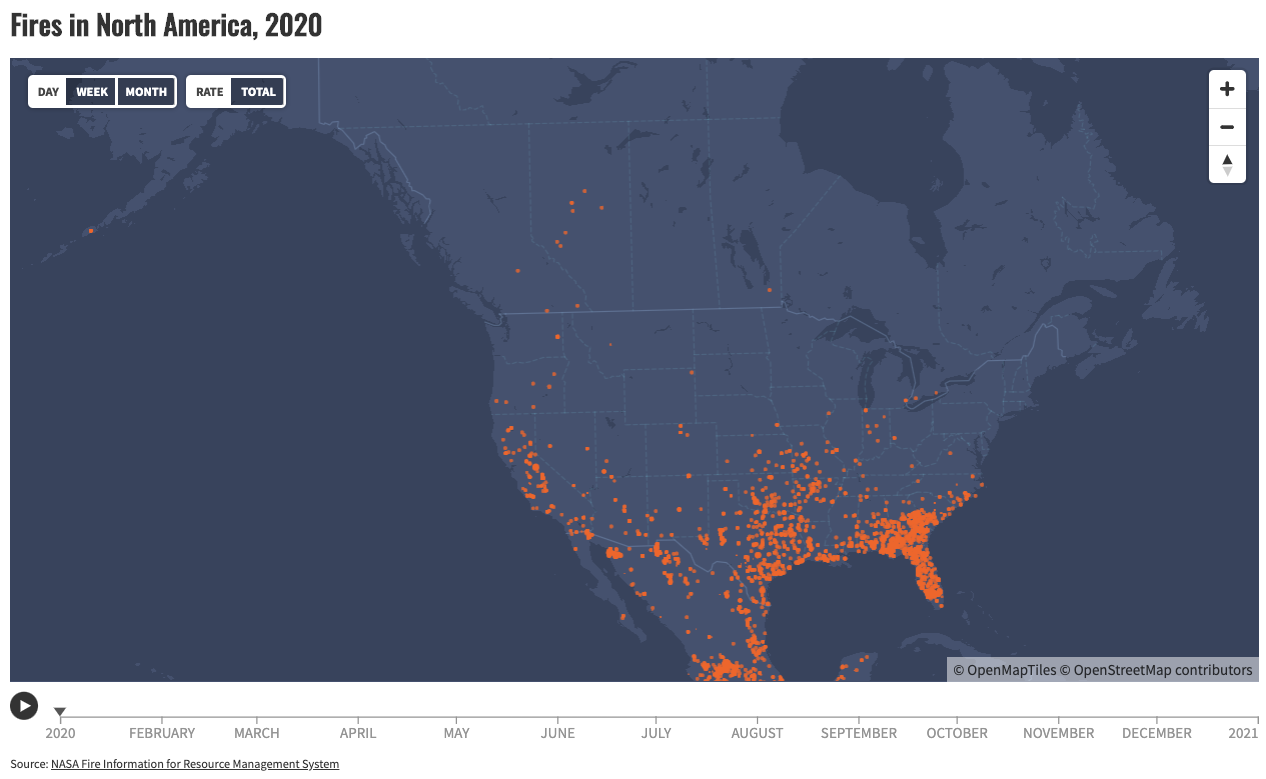

North and South America

California has suffered the most often from wildfire devastation, the blazes now regularly breach city limits to devour the edges of Los Angeles, San Francisco, Fresno, Stockton, Sacramento and San Diego. During 2020, more than 800,000 hectares of land was consumed by fire in the western states of California, Colorado, Arizona, Washington and Idaho.

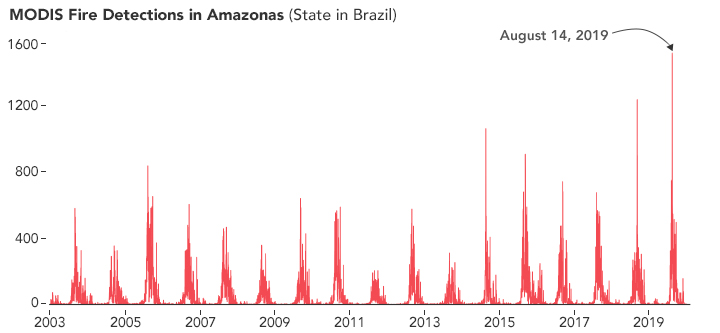

The fires that frequently occur in the Amazon are partly caused by climate change but are all too often man-made, the result of illegal slash-and-burn deforestation. NASA satellites have picked up an increasing number of smaller fires over recent years. Fires in the rainforest reached record levels in 2019, only to be exceeded in 2020.

Although not all wildfires had the impact or the spread of the notorious Californian fires, there were nonetheless 58,950 separate wildfires in the US during 2020. Canada, by contrast, had fewer than 4,000 which was below the annual average.

Click through the graphs above to see the impact wildfires have had in the United States. The map shows that the western and south-western states are most at risk from wildfires but, because of its economic might, any fire affecting California is likely to have the biggest financial impact.

The fires that gripped the state during 2017, 2018 and 2020 were the worst it had encountered, with huge loss of property and life. These dates correlate with the years in which fires had caused greatest economic losses in the US: direct economic losses reached $26.1bn in 2018 but that figure is dwarfed by indirect losses.

Slide the image across to see how the smoke from wildfires translated into aerosol levels (right). The darker the colour, the poorer the air quality index reading.

acres (1m hectares) of land were burned in Alaska in 2019, more than half of the US total of 4.6 million acres

Satellite images show the change in aerosol levels during the 2020 North American fires. Image credit: NASA Worldview

Australia

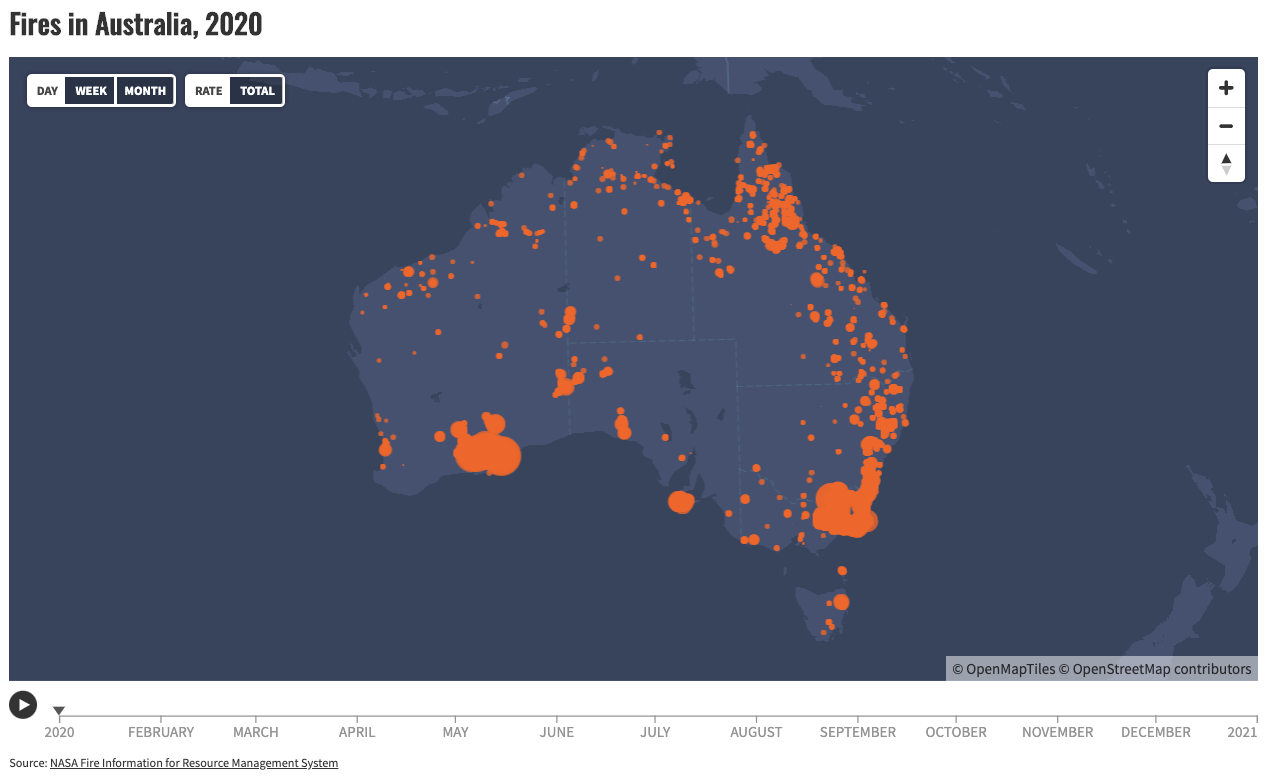

The wildfires – or bush fires – that swept across Australia in 2019 and 2020 caused such devastation that the period has been dubbed Black Summer. Although no stranger to bush fires, atypical heat paired with low rainfall meant that it was almost impossible to contain this outbreak. It threatened some of the country's biggest cities, including Sydney, Melbourne and the capital, Canberra.

These charts show the particularly harsh impact that Black Summer had on Australia's wild animals.

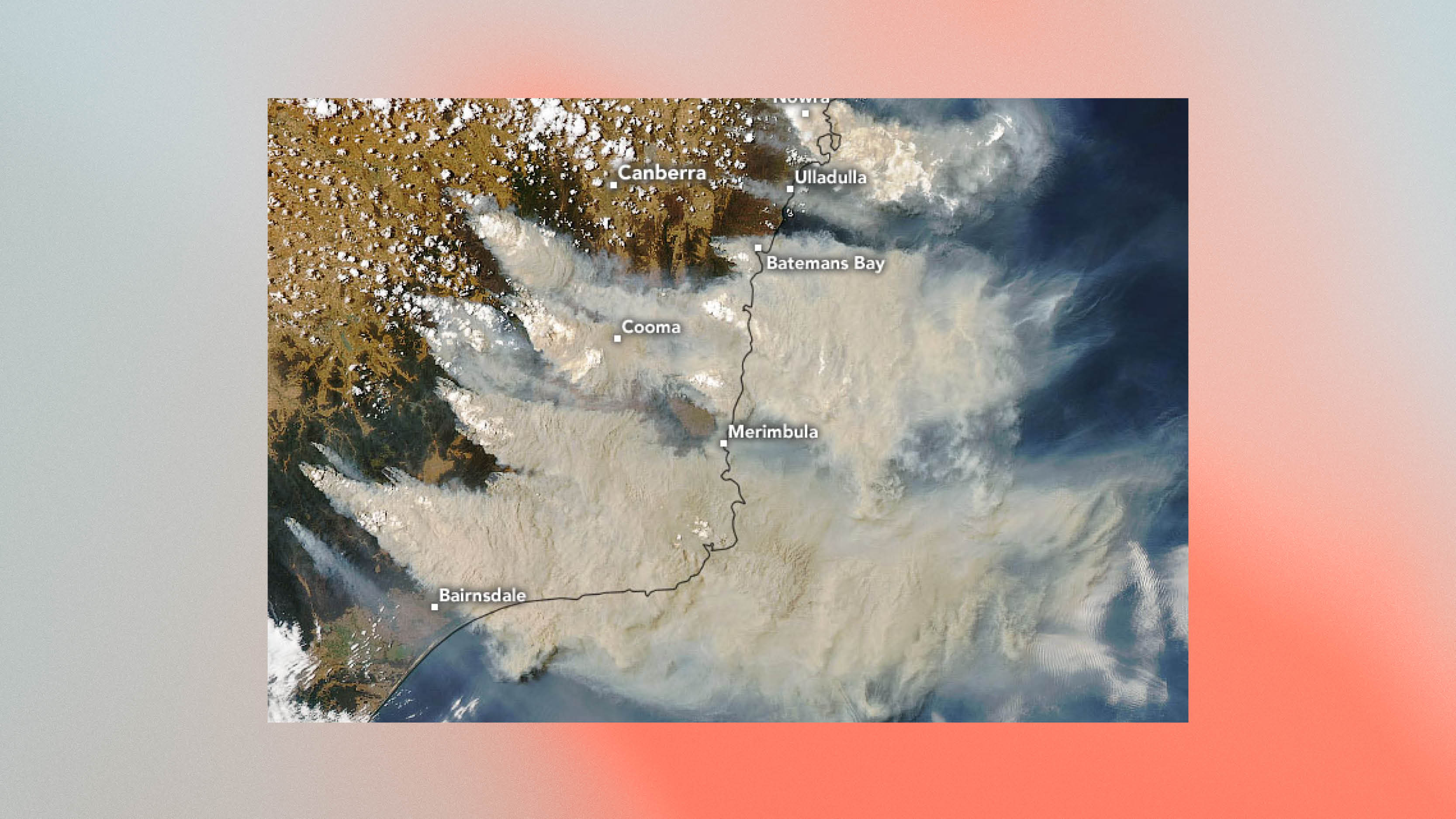

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory

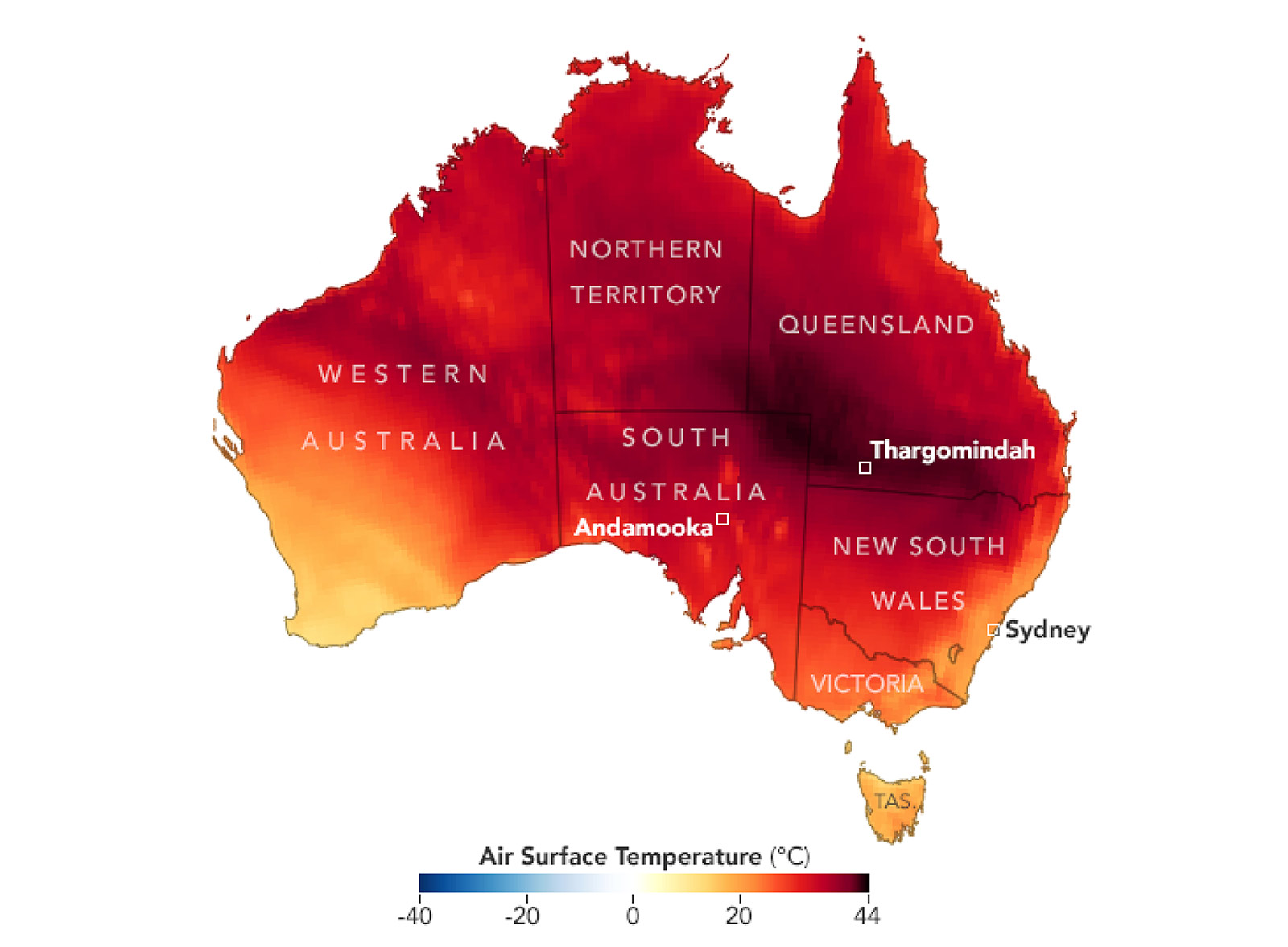

Temperatures in Australia during November 2020 were the hottest for that month on record. Temperatures were about 2oC above average and, at the end of the month, Thargomindah Airport in Queensland and the opal mining town of Andamooka in South Australia recorded the highest temperatures for their states of 46oC and 48oC respectively. The following month, Nullarbor in South Australia reached 49.9oC.

Canberra's Air Quality Index reading in January 2020. Readings above 200 are considered hazardous

Taken in July 2019 and January 2020, satellite images of Orbost, a community in Victoria, about 300km east of Melbourne, show how thick the smog created by the bushfires became.

Satellite images show how smoke from the Black Summer fires engulfed Canberra and its surroundings. On one day in January 2020, the city had a US air quality index reading of 568 – by way of comparison, a cricket match in New Delhi was abandoned due to eye irritation and poor visibility when the figure was lower than 500.

Image credit: NASA Earth Observatory

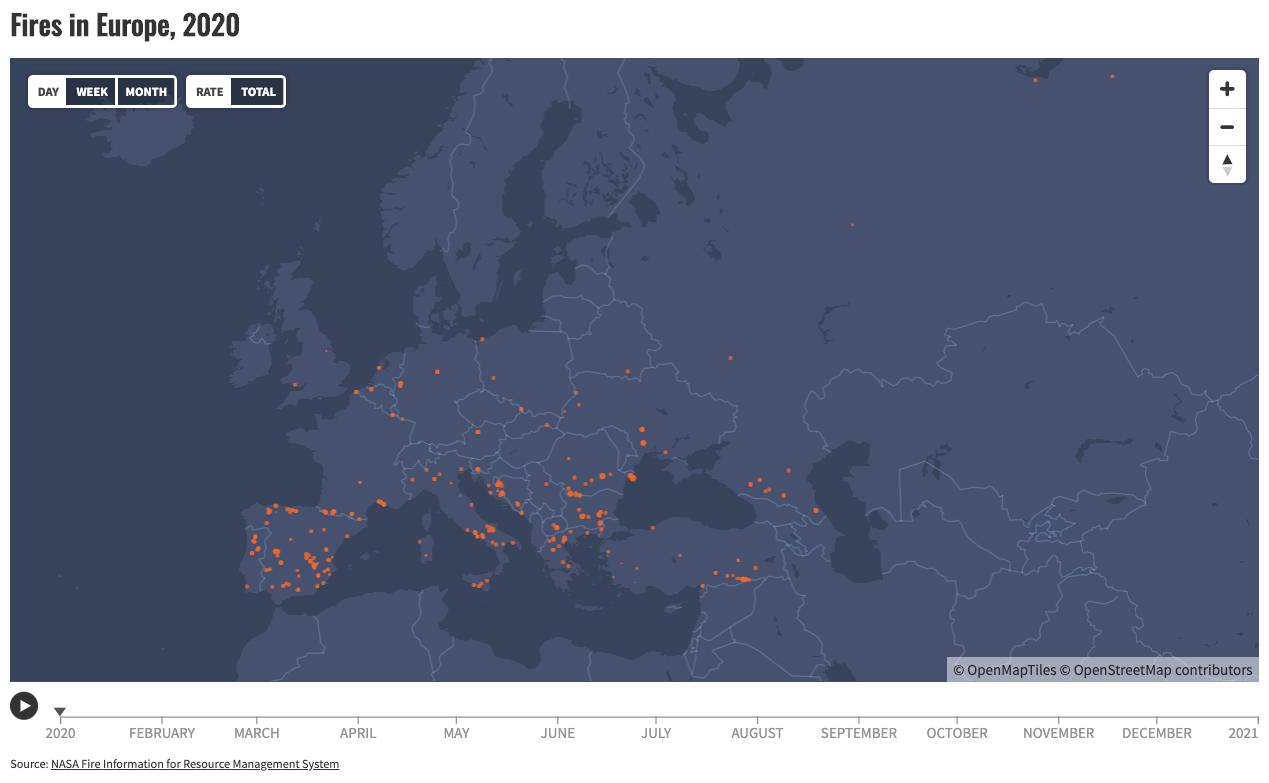

Europe and Arctic Circle

Southern Europe has been a victim of some terrible wildfires in the past decade: in 2017, 66 people were killed during massive blazes in Portugal and, the following year around Attica on the Greek coast, 102 people lost their lives in fires.

More unusually, persistent fires have broken out in areas such as north-west England, Northern Ireland and the Arctic regions of northern Siberia.

Satellite images show the change in aerosol levels due to wildfires over Siberia from 2016 to 2020. Image credit: NASA Worldview

In Siberia, smoke from the 2019 fires alone covered an area bigger than the size of the EU.

is the highest ever recorded temperature in the Arctic Circle on 20 June 2020 in the Siberian town of Verkhoyansk