Image © Getty

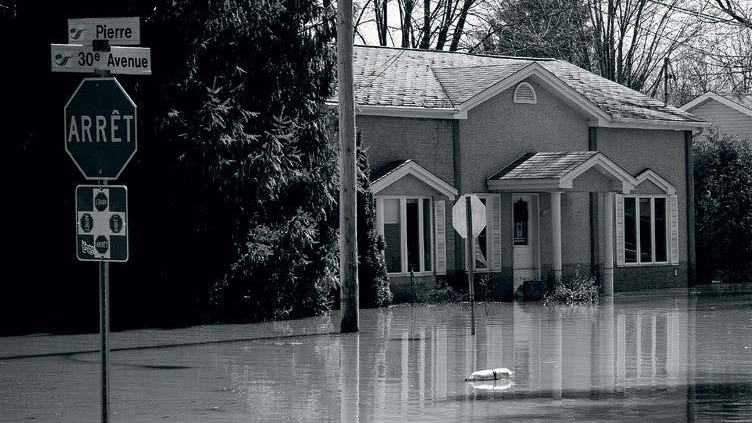

Evacuate today. You may be isolated." The text message sent to people living in suburbs of St John in the north-eastern Canadian province of New Brunswick was stark. After days of torrential rain and with rivers swollen by earlier-than -usual snowmelt, the waterways were running at dangerous levels. Large parts of communities in the province, such as Jemseg, Gagetown and Hampstead, were already under water. Eighty roads and bridges had been closed, and it looked certain that all power, water and sewerage in the city would soon be lost.

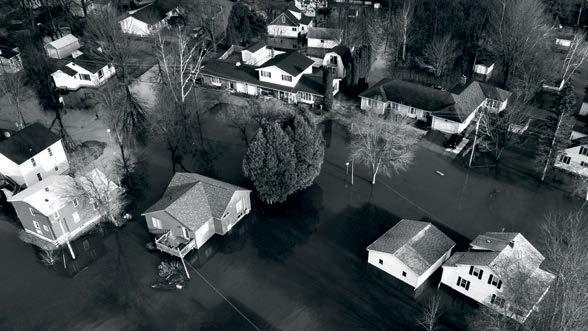

But the spring 2018 floods did not just hit New Brunswick. They were equally bad in eastern Ontario and southern Quebec provinces, where drone images showed police officers, coastguards, firefighters and soldiers filling sandbags and helping people to move out of their houses. Car parks and malls were under water, and protective dikes on riverbanks had been breached everywhere.

This year, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Ontario, Quebec and much of eastern Canada were flooded. States of emergency were declared in St John, Ottawa, Montreal and many other cities, with some places recording up to 6 inches (152mm) of rainfall in a day. At least 16,000 households were affected, nearly 10,000 people were advised to leave their homes, and many thousands more were cut off by rising waters.

Canada has a long history of floods, with many of its cities prone to them because they developed along rivers and lakes. But while the spring floods and snowmelt were fairly predictable, and the height rivers and lakes rose to was largely known, in the past 10 years the floods have been more severe, more frequent and less predictable.

The official database of Public Safety Canada, the federal body charged with protecting people from natural disasters, shows serious flooding now occurring across much of the country most years. "[It is] happening here in Quebec, it's happening in Ontario, it's happening in New Brunswick. What we thought were one-in-100-year floods are now happening every five years – in this case, every two years," said environment minister Catherine McKenna earlier this year.

The reasons for the increasing severity are a mix of climate change, floodplain development, bureaucracy and deteriorating infrastructure, say analysts. According to Canada's Changing Climate Report 2019, more rain is falling and the flood risk increases every year. "Canada's climate is warming at twice the global average. Precipitation has increased in many parts, and there has been a shift toward less snowfall and more rainfall," it says, adding that more intense rain and snow are likely to increase urban flood risks.

But climate change is not exclusively responsible, say others. After the 2017 floods that left more than 5,000 houses in Quebec inundated, Environment and Climate Change Canada's senior climatologist, David Phillips, pointed out that the country's infrastructure is increasingly made of non-absorbent concrete, asphalt and hard building materials. "Climate change is playing a part in the widespread flooding... [but] we've also removed the green infrastructure and replaced it with grey infrastructure. So when that raindrop falls,it becomes immediately a flood drop," he said.

"Canada is the only G7 country without publicly available flood maps. Most are out of date" Jason Thistlethwaite, University of Waterloo

Weathering the storm

The authorities as well as ordinary people are unprepared, warns Don Forgeron, president of the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC). "Canada is not prepared for the increase in damage caused by climate change," he says. "As the only G7 country without a national flood programme, Canadians, our government and the insurance industry have been left dangerously exposed to severe weather risks."

According to the IBC, floods have made up half of Canada's natural disasters since 1970, and government relief spending on them has risen from an annual average of C$40m in the 1970s to C$100m in the 1990s and over C$600m by 2010. This rose to around C$3.2bn in 2013 and C$4.9bn by 2016. The federal government has paid out more in the past six years to compensate provincial governments for flood disasters than in the previous four decades.

Like many countries in Europe and Southeast Asia, Canada has seen the financial cost of flood disasters escalate. Flooding has overtaken fire as the country's costliest and most frequent natural disaster, and is now causing billions of dollars of damage most years. But, because the cost has traditionally been picked up by the provincial governments, who are then compensated by federal government, cities have been lax about investing in flood avoidance.

Following massive floods in 2013, when much of Calgary in Alberta was left under water, federal and municipal governments have withdrawn some compensation and tried to get households to pick up the cost with personal insurance. Quebec and New Brunswick have, in addition, offered homeowners up to C$200,000 (£121,000) not to rebuild after flooding but, because that amount does not even cover the mortgage for many, there has not been a high take-up.

"Because it is costing so much, the authorities now want to pass the buck and make the public pay with insurance," explains Jason Thistlethwaite, professor in the School of Environment, Enterprise and Development at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. "People don't know they are living in high-risk areas, nor do they realise they may no longer be eligible for disaster assistance. In 2016 we surveyed 2,500 people in areas known to be high risk and only 6% of them knew. Canada is the only G7 country without publicly available flood maps. Most are out of date. They have not kept up with flooding and the public has been left behind. People need accessible information.

Thistlethwaite pins some of the blame on municipalities that allow developers to build on floodplains but are not penalised when flooding occurs. "They collect property tax revenue but do not pay for rebuilding costs after natural disasters," he says. "They do not have an incentive to tell people that they are at risk, particularly given that most of the revenue comes from development, it comes from property taxes. So they face a real conflict of interest."

Canada's bureaucracy makes matters worse, believes Korey Pasch, a researcher at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. "There is no single entity in charge of flood risk," he says. "There are separate departments that deal with various aspects of flood risk, from flood mapping, hydrology, flood modelling and flood defence to conservation and disaster assistance. More accurate floodplain maps and improved flood models are needed. Better mapping would provide cities and communities with a better understanding of risks and allow for more informed land-use planning decisions."

Stung by charges of complacency and forced to pay heavily for the rising cost of disasters, the government's Ministry of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness has responded with a raft of measures. It has invested C$120m (£72.6m) in improving early-warning weather and flood systems, and bolstering river defences since the spring 2019 floods. The Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund, launched in May 2018, has C$2bn (£1.2bn) available to support large-scale infrastructure flood fire and other defence projects.

The money has been welcomed, but with reservations. To qualify, projects must have a price tag of over C$20m (£12.1m) and communities must find half the costs. This, say many small towns, unfairly favours large cities such as Toronto that already have access to disaster funds, but excludes hundreds of communities that don't have C$10m (£6m) to spare for the many small-scale projects that could make the difference to a town being flooded.

According to Infrastructure Canada, the federal department that manages the fund, more than C$1bn (£606m) has so far been allocated to 29 projects, with nearly a quarter going to a single project to prevent communities on Lake Manitoba and Lake St Martin flooding as they did in 2011 and 2014.

Minister of public safety Ralph Goodale blames climate change for many of the traumas Canada is experiencing. "All levels of government are learning some expensive lessons from this flooding experience of the last few years," he says." The message is, don't think climate change is going away. It's going to get progressively worse rather than better. More unstable weather can give precipitation that dumps around a year's worth of moisture in a day or two.

But Thistlethwaite warns that the floods will worsen for many reasons. "We have a lot of developments in high-risk areas, and that number is increasing," he says. "We have outdated infrastructure which we cannot afford to replace. And we have changes in the climate which are going to increase substantially. The next 50 years are going to be a wild ride."

"All levels of government are learning some expensive lessons" Ralph Goodale, Canadian minister for public safety