Image: Facebook

On the western edge of the remote Swedish town of Luleå sits a nondescript, largely windowless building surrounded by fir trees. Its huge footprint, which would cover four and a half football pitches, and modest height – the roofline invisible below the tips of surrounding trees – testifies to its contents. Thousands of computer servers arranged in starkly lit rows, blinking and humming for 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Architecturally it has nothing to recommend it. Its boxy, oblong layout and stark, flat planes bring to mind a modern prison or 1970s-era factory. For visitors to the neighbouring bird sanctuary it justifies neither a detour nor a second glance. But, with a few hundred units like it scattered across the world, it is among the modern era’s most important environmental saviours.

Ten years ago, carbon emissions from the global data industry looked like a disaster waiting to happen. As the data age entered its stride, the hardware required to transfer, store and crunch the world’s mushrooming data cloud was already devouring more electricity every year than Australia.

In the intervening decade, an explosion of demand would add a seemingly impossible load: six times more computational work, 26 times more storage and 11 times more internet traffic, according to a February paper in the journal Science. Scale up the power consumption from 2010 levels and today the industry should be sucking up more than twice the electricity consumed by the entire continent of Africa.

But the seemingly inevitable emissions catastrophe never materialised. The astonishing reality is that, since 2010, power consumption by the world’s data centre industry has barely budged. Thanks to huge purchases of renewable power by the major technology firms, meanwhile, today’s emissions from the data centre industry are a fraction of 2010 levels.

Facebook and Luleå’s change of luck

Luleå, a coastal town less than 100 miles from the Arctic circle, with a population just shy of 50,000, is known for medieval wooden houses and an embarrassment of natural resources. Circled by huge steel deposits, endless forests and a thriving hydroelectric power industry fed by several fast-flowing rivers, its economic prosperity seems assured.

But 10 years ago it was down on its luck. Luleå’s biggest industry was reeling from a last-minute decision to pull a new steel plant, with roads built, ground prepared and thousands of new jobs promised. Now the town watched, powerless, while the fruits of the budding Luleå Technical University were steadily cannibalised from abroad – each new promising academic spin-off immediately snapped by a major US tech firm and relocated to London, Berlin or Silicon Valley.

“There was a negative feeling about the place. Not many interesting jobs. A culture that we didn’t like our town. Young people wanted to get out, for Stockholm, Gothenburg or abroad,” says Luleå’s mayor, Lenita Ericson.

Then, in 2011, Facebook came calling. The world’s most popular website, it was seeking a spot for its first hyper-scale data centre beyond US soil. The huge server farm would consolidate the billions of photographs, messages and likes into a single storage and processing behemoth, where huge efficiencies in computing and power consumption would help attack the companies spiraling electricity bill. In Luleå, it liked what it saw.

At the time, most of the world’s data was still saved and processed on local company servers or personal computer hard drives. To the largest tech companies the process was painful to watch. A hotchpotch of small, inefficient and expensive resources scattered through the world’s cities and towns, it was crying out for consolidation. Far better to corral the world’s data into a few super-computing centres in locations where power and land were cheap, and the technology giants could farm huge efficiency gains from the scale of processing and storage.

The cloud’s silver lining

A new era of cloud computing began. Its heralds – giants such as Facebook, Google and Microsoft – scouted the world for sites to locate the hyper-scale data centres to make it happen. These vast hangars housing hundreds of metres of server racks, each supporting billions of computations per second and storing an increasing share of the ballooning cloud of data, sprung up like mushrooms after rain. In a little under six years to September 2019 numbers tripled to more than 500.

Smaller ones grew around existing hotspots in Europe’s major capitals, where mission-critical tasks required data centres to be located exactly where business was done to limit time delays. “London, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Paris – they all have financial centres that need ultra-low latency connections – less than a few milliseconds – for trading,” says Emma Fryer, who oversees Data Centres for techUK, the UK trade body.

The US, with its stranglehold on the booming internet industry, claimed the lion’s share. Most of these clustered around “Data Center Alley”, a central highway through the quiet town of Ashburn, 30 or so miles west of Washington DC. In 1992 a group of local network providers had joined forces to connect one of the world’s first internet exchanges there. Today, across the wider district of Loudoun County, data centres sprawl over nearly 10.8m ft2 (1.7m m2).

Ireland formed another hub as technology giants’ data centres joined their European company headquarters, attracted a few years earlier by generous tax breaks. The European Commission subsequently ruled that these incentives amounted to illegal state aid – a decision that the Irish government successfully overturned on appeal last month (July 2020).

The last cluster was in Scandinavia, thanks to the region’s surfeit of cheap power – a data centre’s oxygen – and strong digital connectivity. As Facebook hunted for a suitable site, Luleå, which had an abundance of both, looked irresistible.

The hydroelectric power running off local rivers was, crucially, reliable. Luleå Technical University promised a ready supply of skilled staff. And, even by Scandinavia’s standards, Luleå boasted exceptional digital connectivity, despite, or rather because of, its remote location.

“The government had realised that, without connection to a digital highway, towns like Luleå would be dead,” says Hakan Ylinenpaa, a retired professor at Luleå Technical University and historian of Luleå’s data centre industry.

No sooner was it open in 2012, the Luleå centre went straight into overdrive, hoovering up global computing demand. With a few hundred peers scattered across the globe, it helped transform global computing almost overnight. In 2010 two out of 10 server computations were done via the cloud at one of these hyper-scale data centres; by 2018 that had grown to nine out of 10.

During that time, nanotechnology and improved building design had enabled data centres such as Luleå’s to reduce the energy required to perform a single computation by 90%, a transformation hard to find a rival for in modern industrial history.

Smarter software, less power

Moore’s law, whereby the number of transistors that engineers could fit onto a computer chip doubled every two years for the quarter century ending in 2000. Volume servers – the workhorses of large data centres – did five times the work of equivalently sized ancestors in 2000, using a quarter of the power for every computation and one ninth for every terabit saved.

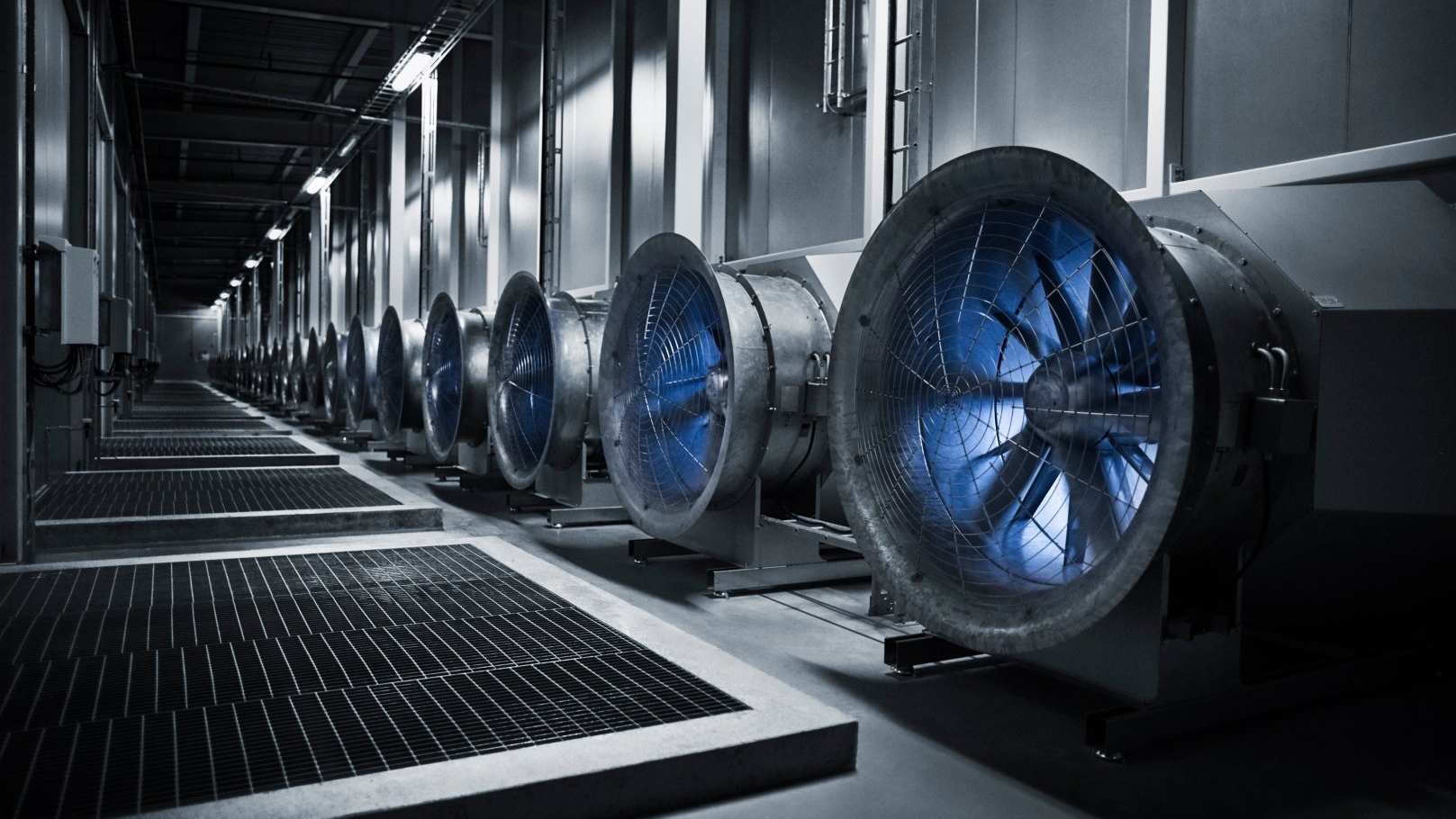

Hyper-scale data centres, meanwhile, have reduced to a fraction the power required to keep servers cool.

Computation is a trench battle with thermodynamics. “All you can do with electricity is convert it from power to heat,” says David Watkins, of Virtus Data Centres, a UK data centre operator, which charges large corporate clients based on server space and power needs.

The importance of keeping cool

Cooling thousands of servers together is far more efficient that cooling them separately, in a thousand different IT departments across the world, even before the efficiency gains wrought by recent improvements in cooling system design.

Andrew Jay MRICS, head of EMEA Data Centre Solutions at CBRE, estimates that 80% of the cost of building a data centre (before customers’ servers arrive) is equipment, with the rest split half and half on land and the building. Much of this is cooling kit: for Watkins, today’s hyper-scale data centre “is basically a very well-connected fridge”.

His fridges run at 24ºC (uncooled, they would reach 35ºC in 10 minutes – most shut down at 30ºC – not long after, the circuit boards would start to melt). The temperature, set by a US industry association, provides a lodestar to guide manufacturers building better server hardware. It has increased 3 degrees in six years: more robust servers can run hotter, vastly reducing the power required to cool them.

In most data centres open rows of servers have now been replaced by a series of heat-proofed units ensuring only the servers, not the air between them, is cooled. “They are like little houses. You’re no longer cooling the whole hall, just a tiny bit of it,” says Mark Trevor MRICS, who, until recently, led Cushman & Wakefield's EMEA Data Centre Advisory Group.

With most efforts spent improving data design focused on better cooling, today almost all are cooled power-free (although power is required to pump the cool air in and out of the building). In Google’s €500m Dublin data centre, cooling hasn’t required air-conditioning since it opened in 2012.

All told, the huge power efficiency strides made prior to 2000 have continued largely unabated, according to Jonathan Koomey, a pioneer of research into computing's energy efficiency.

"Improved building design saw data centres reduce the energy required to perform a single computation by 90%, a transformation hard to find a rival for in modern industrial history"

Embracing renewable energy

The remaining ingredient to the quiet transformation that hyper-scale data centres have wrought on global computing’s environmental footprint has been the adoption of renewables by their owners.

Last year Google and Apple met their power consumption with 100% renewable energy; for Facebook the proportion was three quarters; for Amazon and Microsoft it was half. Led by Google – which alone bought more than Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft combined – the six largest private sector buyers of renewable energy in 2019 were all technology firms. In the UK, where independent operators run data centres in which space is leased by technology companies and other users, 77% of electricity purchased in 2019 was renewable, according to techUK.

Towards a dirtier future?

For all the alchemy it has worked in meeting the world’s insatiable appetite for data without saddling it with a calamitous emissions footprint, the future of the hyper-scale data centre looks less secure.

Despite a projected 50% increase in workloads, power demand from the world’s data centres will not budge between now and 2021, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts. The problem is that, by then, an increasing number of them will be in Asia, fed by a much dirtier power mix.

With the spread of internet and mobile use faster in Asia than anywhere else in the world, hyper-scale data centres are springing up all over the region. At the start of last year, those under construction in China outnumbered those in operation by nearly three to one, according to Singaporean Bank DBS. By 2021, having had fewer than one-third in 2018, Asia will host the majority, according to the IEA.

If Western tech firms go after the commercial opportunities of delivering the internet to a new generation of Asian consumers, they could bring their appetite for clean electricity with them.

Don't bet on their chances. In China, by far the largest market in Asia, the leading tech behemoths operating the country’s data centres – including Alibaba, Baidu and Tencent – show no signs of losing ground to Amazon, Google and their US peers. And in 2018, 73% of power feeding China’s data centres was generated by burning coal, a report by Greenpeace and North China Electric Power University found. By 2023, with power consumption up two-thirds and no increase in renewables procurement, the CO2 emissions from China’s data centres will be just under half of those generated by the entire economy of the UK.

As problematic as the shift to Asia is the risk that the data centres responsible for storing and crunching the world’s data cloud may be about to splinter again, undoing the efficiency gains of the last decade.

Enter the internet of things and the age of micro-cells

Societies West and East are set for a deluge of new internet-connected gadgets, supporting everything from tele-medicine and mobile gaming to self-driving cars. McKinsey estimates the number of devices comprising the internet of things” will triple between 2018 and 2023, reaching $43bn.

Where they will send their data for processing and storage is still unclear. But at least some of them – those enabling self-driving cars, for example, where glitches in data transfer could be fatal – will need local processing hubs to limit delays.

Such mini data centres, located in the heart of urban centres where processing needs are largest, could become as ubiquitous as today’s unassuming street-side phone cable boxes. “These micro-cells may soon be on every lamp-post, in every building and embedded into the facia of every McDonald’s in the country,” says CBRE’s Jay.

All this could result in the work done cutting power consumption in hyper-scale data centres fast being undone by a new wave of local micro-centres, a return to the bad old days of inefficient, distributed, power-hungry computing.

“You’re talking about millions of data centres across the globe supporting perhaps trillions of devices one day. All the academic papers say that data centre power consumption is going to be flat but that’s not where the action is going to be,” says Dr Lotfi Belkhir, an engineering professor at McMaster University in Ontario, Canada.

Whatever happens next, the hyper-centre boom will leave its mark.

In Loudoun County, which today claims to host 70% of the world’s internet traffic, the data centre industry kicks up $15 in taxes for every dollar it consumes, a windfall that has cut local household taxes by 20% in a little over a decade.

Buddy Rizer, the county’s head of economic development (dubbed “Godfather of Data Center Alley” by local press) struggles to conceive of life without the sector. “We’re building two or three new schools per year. It’s hard to think of us going back to how things were.”

In Luleå, Facebook will soon start on its third hyper-scale centre on its western site, the company’s presence secured in part by a 2017 rule change that cut Swedish taxes on electricity supplied to data centres by 97%.

Once built, the American giant will have ploughed nearly $1bn into the remote Swedish town, which by then will boast more than 20 hyper-scale data centres, among their tenants other multinationals including BMW. The Facebook effect has acted as a magnet to smaller technology companies seeking to provide it with services and attracted to the expanding tech cluster.

Luleå Technical University’s promising spin-offs now stay squarely put and mayor Ericson isn’t losing any sleep over a brain drain. “The spotlight has been put on Luleå. Jobs have grown and we have diversified Luleå’s industries. Small steps have made the town roud.”

This article was updated on 3 Aug 2020 to take note of the Irish government’s successful appeal.

"The risk is that the data centres responsible for storing and crunching the world’s data cloud may be about to splinter again, undoing the efficiency gains of the last decade"