Lovers of the Fosters & Partners building, the Gherkin, should stop reading now, because by 2027 it will have disappeared. Or at least it will be invisible to anyone not standing on a specific hillside in north-east London – crowded out of the skyline it once dominated by a whole new breed of bigger, brasher and less lovable skyscrapers.

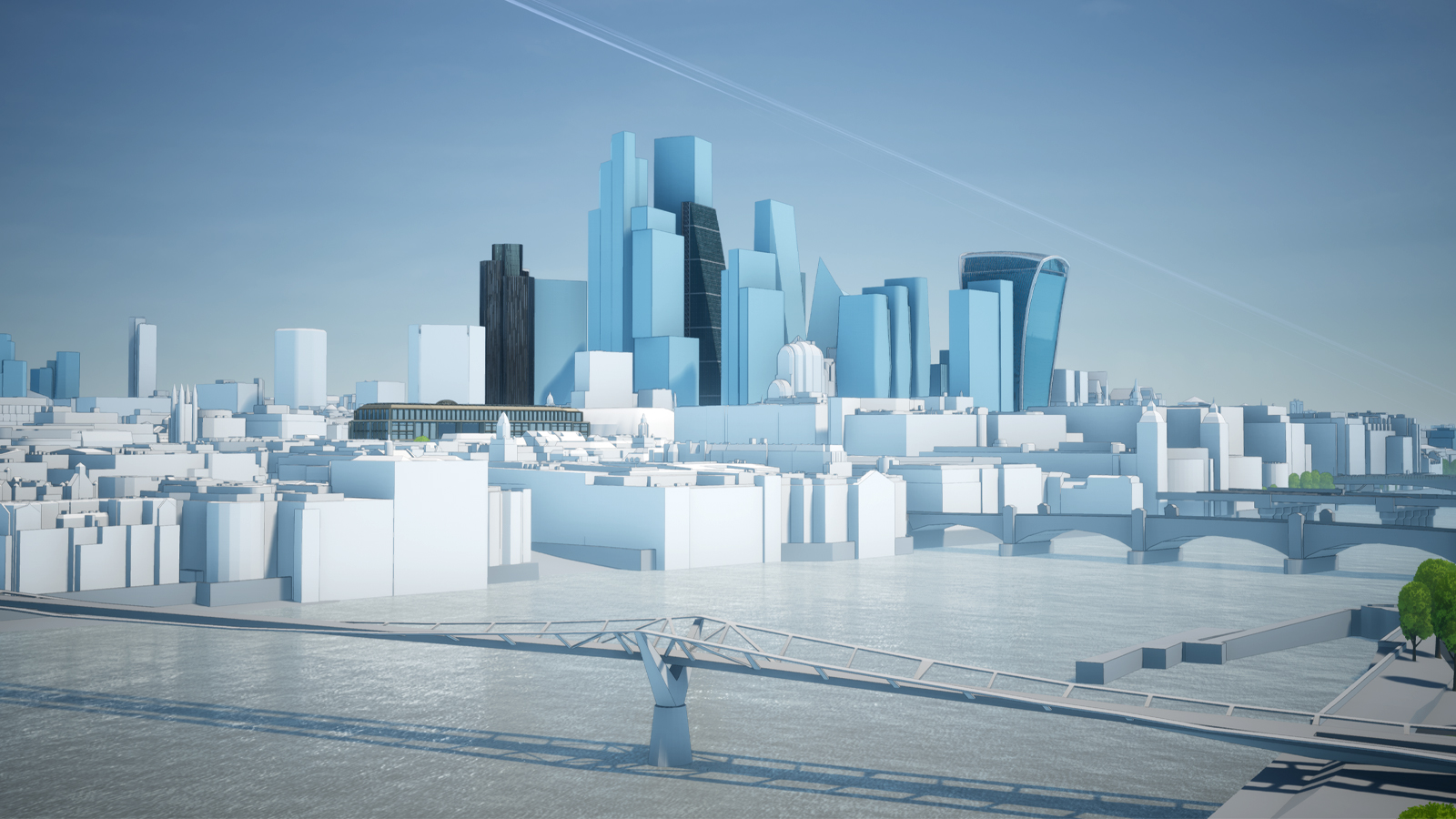

That’s the outcome predicted for the future of London’s skyline by Sandor Petroczi, director of AccuCities, a company that provides 3D models of many UK cities. These include not just high levels of detail regarding existing buildings but are constantly updated with information on proposed and greenlit buildings too. This provides a window into what a cityscape might look like in a few years’ time, when the planning applications of today become the built environment of tomorrow.

“We take information about what buildings are being proposed and then we import those into the model,” says Petroczi. A user could also decide that they want to see how light responds to the façade of the building, or, given that these office towers do embody quite a lot of corporate ego, just how big and thrusting it will look against its yet-to-be-built neighbours. Most importantly, will the CEO be able to see anything from his corner office or will he just be eyeball-to-eyeball with the CEO in the next block?

The company describes its models as digital twins of the cities they reproduce: the buildings aren’t just blocky renderings but completely recognisable and accurate to within 15cm.

Petroczi and his business partner, Michal Konicek, met while working for another company that offered similar computer modelling but for just one large client. They saw the potential in providing an even more detailed and affordable application to a much wider clientele and set up AccuCities four years ago. “We thought the quality and detail of some of the older maps could sometimes be questionable, so we decided as the new players on the block, to make it more accurate,” says Petroczi.

The software has obvious benefits to architects, urban planners and engineers (although it’s also used by the increasingly realistic gaming industry), with big name architectural practices such as Make and KPF among their users. “All the stakeholders want to know what the area that they are designing in will look like when their building goes up and, with a big development, that might be in eight or 10 years,” says Konicek. “There is currently no requirement by local authorities to provide 3D models, but our customers can see what will be there in a few years’ time. This matters really matters in a place like London, because it’s getting so crowded and the distance between buildings can be just a few metres.”

There are obvious environmental benefits to using AccuCities data as well. The accuracy of the measurements makes it incredibly useful when testing how a theoretical building might create, for example, a wind tunnel. But it’s not just about comfort because once you have that information, you can scale it up and see how tweaks to the building can redirect the wind to the point that it might be worth installing turbines that will help to power the building. Alternatively, it could measure whether there will be enough light hitting a roof to make solar panels a realistic investment. The data is also very useful when modelling flooding risk and recently it was used as part of a project by a designer in residence at the Design Museum to illustrate the microbial diversity of certain London streetscapes.

Konicek and Petroczi hope that two factors in particular will mean their model is used more and more in this realm. The first is regulatory pressure from planning authorities to provide much more detailed environmental reports as part of the application process. The second is developers waking up to the fact that implementing green measures and ensuring biodiversity might be looked upon kindly by planners.

They are also keen to partner with universities and other not-for-profit institutions that might find their models useful for building their own studies and analysis. While there is no disputing the precision of the AccuCities models, such detail can be a two-way street, as it gives a designer little cover: there is no space for the vague, sun-always-shines ‘artist impressions’ of future projects which rarely give a realistic sense of scale or just how they will fit in with their surroundings.

“Everyone wants to know what the area that they are designing in will look like when their building goes up and, with a big development, that might be in eight or 10 years” Michal Konicek, AccuCities

“You must have seen renders like the Garden Bridge which are quite subjective and always made the project look good,” says Konicek. “With our model, there is much less room to hide, and some users do see it as a double-edged sword: they know that they will be scrutinised much more because they don’t have the privilege of choosing the angles. But most of our customers see this aspect as a welcome development, helping them to create better designs.” Had the model been available during Boris Johnson’s tenure as Mayor of London, perhaps an awful lot of time and even more public funds could have been diverted from the failed Garden Bridge project – the wind modelling alone would have shown it was unfeasible.

There is every chance that future leaders will not be able to indulge their flights of fancy with such abandon. Although AccuCities has only produced maps for London, Bristol, Birmingham and Cardiff so far, it is theoretically possible to see any area of the UK as all the relevant data to build a model is there.

The company is beginning to venture overseas, having produced models of Dublin and Detroit, and Konicek would like to do more as he believes that providing the type of future landscapes that AccuCities is capable of has a role to play. “In a lot of countries there’s just no overall control,” he says. “Developers submit their designs and how they will all work together is not considered to the same extent that it is here.”

“With our model, there is much less room to hide, and some users do see it as a double-edged sword: they know that they will be scrutinised much more” Michal Konicek, AccuCities

%20copy?$article-big-img-desktop$&qlt=85,1&op_sharpen=1)