Alfriston Clergy House is a small timber-framed, thatched property tucked alongside St Andrew's Church in Alfriston, East Sussex. While generally unassuming, its significance far outweighs its humble scale.

Not only is it a largely intact medieval building, it was also the first property saved by the National Trust.

Trust acquires house after 500-year evolution

The property was built for the new vicar of Alfriston between 1399 and 1407 as a Wealden hall house, a type of vernacular medieval building, and as such it followed a common floorplan. In the 1550s, though, the service rooms in the west end of the house were rebuilt and a cross wing introduced, and a floor inserted into the hall to create a second storey.

Two centuries later, the property was subdivided into two cottages, a rear lean-to corridor was added and the cross wing partly demolished. Between 1889 and 1894 the building was near derelict, but was restored under the then vicar Rev. F.W. Beynon, who among other things removed the floor inserted in the main hall.

However, his project ran into difficulty, and it was only when the then newly formed National Trust approved its first purchase of a building in 1896 that the house's future was secured.

One of the trust's founders, Octavia Hill, worked closely with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) and the latter's recommended architect Alfred Powell to conserve and save the building.

In the property's 2019 conservation management plan, curator George Roberts noted that Powell had overseen the maintenance of the building until 1934 before this responsibility was passed to William MacGregor, another SPAB-approved architect.

Both maintained a sympathetic approach to their work, mainly with the aim of preventing damp. The trust also limited visitor access during the early years, but it was fully opened to the public in 1977.

Flaking paint prompts investigation of damp

Despite ongoing cyclical maintenance, the property's condition continued to present numerous conservation issues. One of the main considerations was the condition of the internal painted surfaces: large areas throughout the building were crazing and flaking, an issue initially believed to be a result of damp.

The trust's approach was to view the building holistically and pinpoint any weaknesses or defects that could be causing this. The priority was to assess the thatched roof and timber frame. The roof's existing ridge had reached the end of its serviceable life and had to be replaced, although the rest was in a good condition.

To carry out the survey of the timber frame, the trust instructed specialist remedial surveying and consultancy service Hutton & Rostron in September 2021. Its findings were positive, with only a few areas of minor maintenance repair required. The survey also ruled out any major beetle infestation in the timber, which could have indicated increased moisture levels.

With the external envelope and structure of the building found to be in a good state of repair, the investigations moved inside. As Alfriston is a largely unaltered medieval house, its main areas would historically have been heated by fires. This would have reduced the relative humidity (RH) by raising the temperature and ventilating the space through the draw of the chimney.

Today, portable electric radiators are used if needed. So, as part of the investigations, the property's RH was monitored and reported to be above the accepted tolerance of 60–65%.

Buildings such as this were originally designed and built to breathe, so a high RH is not always an indication of defects. By being permeable, such buildings passively enable moisture to pass through gaps in the fabric, chimneys and the plaster itself. Therefore, the question was whether something was impeding this process.

As the chimneys were open and known gaps had not been blocked, the trust suspected the walls themselves were causing the problem. So it wanted to determine whether an inappropriate plaster or paint had been applied internally that may affect the passage of moisture through the fabric.

'Despite ongoing cyclical maintenance, the property's condition continued to present numerous conservation issues'

Alfriston Clergy House's main hall © National Trust Images/James Dobson

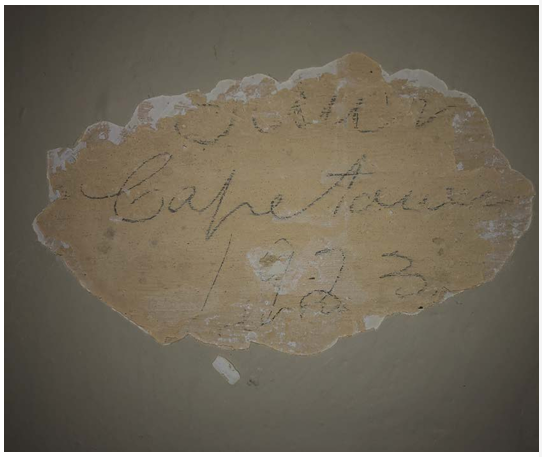

Graffiti by visitor from Cape Town, dated 1923 © Crick-Smith

Finishes analysed to identify source of defects

In October 2021, the trust commissioned Ian and Michael Crick-Smith, experts in historic paint analysis, to undertake a detailed investigation of the finishes back to and including the plaster substrate.

Their survey found the substrate throughout was a lime plaster with no evidence of any gypsum-based ones. Over the substrate were distinguishable schemes of soft distemper. However, these lay beneath layers of modern alkyd paint systems. The two paint types are not compatible as they each are designed for distinct roles.

Soft distempers are suitable and traditional for a building of this type – they are permeable, with an animal glue binder, and they can include pigments to provide colour. Distemper is also water-soluble, and is sometimes washed off before a new coat of distemper is applied. This was not the case at Alfriston Clergy House, though, and meant there were several friable layers in the paint build-up.

Modern alkyd paints provide a smoother finish; but the nature of the alkyd is that the paint film will tighten on to a surface as it dries. Where the underlying layers are unbound soft paint types, the stresses exerted by the alkyd schemes cause these layers to fail. In effect, the tightening of the alkyd causes the decoration to spall away, curling back.

The permeability of these finishes to vapour is also different: the lime plaster and the soft distempers are breathable, but most modern paint systems including alkyd paints are not, or at least not to the same extent.

Accumulated hydraulic pressure causes the moisture to take the route of least resistance to the surface. Where fracture lines have occurred due to the drying of the alkyd, the moisture further weakens the already compromised soft distempers on the substrate, accelerating the losses of painted material from the surfaces.

Survey informs sympathetic remedial measures

These results show how materials interact with each other to exhibit symptoms that could be misunderstood as damp.

The proposed remedial works at Alfriston Clergy House involve the removal of the modern paint by careful mechanical process, and had the Crick-Smiths' investigation not taken the time to understand the building system and proceeded on the basis that damp were present, this could have been a damaging, intrusive and costly mistake.

Trials for removing the modern paints have already been carried out, with the surprising revelation of historic pencil graffiti – some dating to the 1920s – and crude plaster patterns.

The patterns are thought to have been applied by the plasterer when working in the house, possibly in the late 19th century. The graffiti meanwhile are still legible and believed to have been left by some of the earliest National Trust visitors to the property, almost 100 years ago. Both of these increase our understanding of the building and its significance.

Simon Davis MRICS is a senior building surveyor at National Trust. He wishes to thank the property team at Alfriston Clergy House, the Crick-Smiths and Dr Samantha Organ FRICS for their contributions to this article

Contact Simon: Email

Related competencies include: Building pathology, Conservation and restoration