In some buildings, bricks of different sizes are used on different elevations

Each and every brick building is made up of bricks with particular and unique characteristics. When brickwork has suffered decay there will often be a need to replace those that are no longer fulfilling their structural and aesthetic purpose. A careful assessment of which should be replaced and which are sound enough to remain in situ will be required.

Following this, the process of finding suitable replacements begins: this needs careful planning and the balancing of diverse characteristics including size, shape, water absorption rate, colour and type.

There may be occasions when more detailed consideration of the heritage value of bricks is required, for example Tudor or gauged brickwork. Where this is the case, conventions from BS 7913:2013 Guide to the conservation of historic buildings and guidance from organisations such as Historic England and Historic Environment Scotland should be consulted.

In all cases, it is vital that the unique characteristics of the bricks are considered in order to ensure structural integrity and – where possible – maintain an aesthetic. Treating brick replacement work with adequate care and consideration will allow the rich heritage of brick buildings in the UK to survive long into the future.

Characteristics for consideration

Matching the type of brick used in a building is vital for both the aesthetic and the technical performance of the brickwork following repair. The type is generally related to the method of manufacture, with, for example, handmade bricks being moulded manually and extruded bricks formed using a machine.

The material used can also influence the typology of brick; a common or colliery shale brick is one manufactured from shale, a tough clay often extracted during coal mining operations.

Identifying the type of brick used in a wall is often the first part of specifying and locating suitable replacements. Some types are increasingly hard to source, with colliery shale bricks in particular difficult to match exactly, although some companies provide reasonable substitutes manufactured from other materials.

Brick types can include:

-

handmade brick: bricks moulded manually, often with irregular, variegated appearance in terms of colour, and smaller than machine-made bricks

-

common brick: also referred to as colliery or composition brick, these vary significantly in both texture and colour, and are generally rough to the touch with variegated colour

-

glazed brick: uniform, glossy appearance, manufactured in a wide range of colours

-

engineering brick: often a darker colour and a dense appearance

-

special-shaped brick: moulded in a non-standard shape to fulfil a specific decorative or technical purpose

-

pressed facing brick: pressed during mechanised brick production, generally with a uniform texture and colour to give an attractive appearance

-

rubbing brick: softer and free of inclusions such as stones or lime to allow cutting and rubbing in gauged brickwork

-

extruded brick: also known as wire-cut, these are produced by extrusion, often with characteristic drag marks on the face.

When matching bricks for repair work, it is also important to match the size of the new ones with the old as much as possible. Modern metric bricks are unlikely to be suitable replacements for traditional ones: before the metric system was adopted in 1965, there was considerable regional variation in the size of bricks used throughout the UK, with those used in the north of England being larger than those in the south, and those in Scotland larger still.

Bricks also tended to be built to a particular gauge, which refers to the height of four courses of bricks with their mortar joints. Again, both the north of England and Scotland had specific regional gauges to which brickwork was often constructed. If the size of brick used in repair work is incorrect, then the gauge will also be wrong (see photo).

As a general principle, measuring the dimensions of ten bricks in different parts of a wall that is being repaired will give a good indication of size. Buildings may, however, have been built with bricks of different sizes; for example, a principal facade may be constructed of thinner facing bricks, with side and rear elevations using larger common or colliery bricks. Care must be taken to ensure that the correct size of bricks is used for both aesthetic and structural reasons.

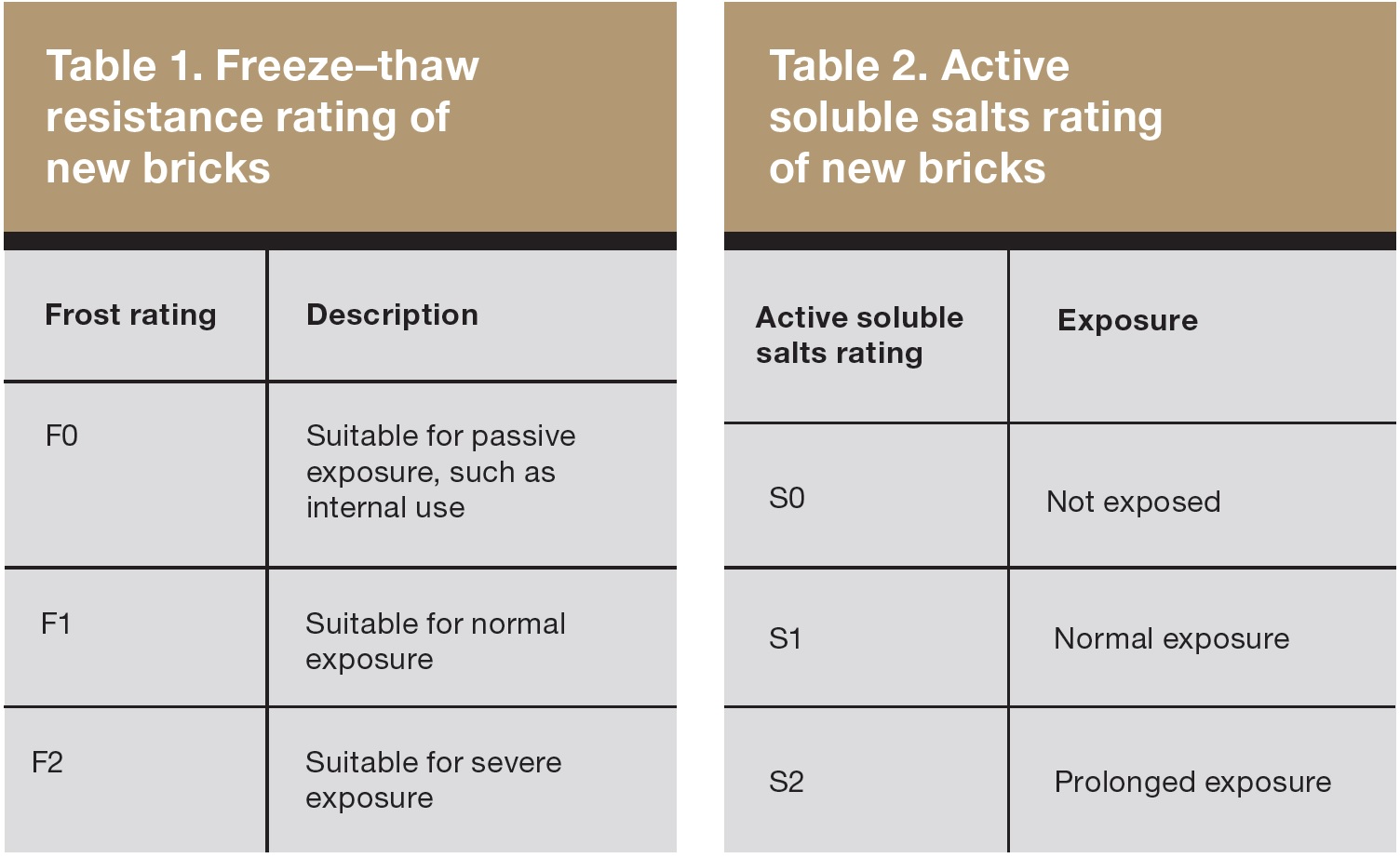

Frost resistance is one of the technical considerations when sourcing replacement bricks for repair work, and any new bricks must be suitable for the exposure to which they will be subject. The frost resistance of new bricks is defined under BS EN 771-1:2011+A1:2015 Specification for masonry units: Clay masonry units by a freeze-thaw resistance rating as shown in Table 1. For most external repair work, an F2-rated brick is likely to be required.

The soluble salt content of new bricks is another consideration, and is also defined under BS 771-1 (see Table 2). Generally, an S2-rated brick will be most durable for external repair work. Although there may be exceptions to this – for example, where handmade bricks are required to replicate early brickwork – an F2–S2-rated brick will as a rule be the most appropriate.

'Frost resistance is one of the technical considerations when sourcing replacement bricks for repair work'

The water absorption rate of any new brick is also significant, and it is possible to remove bricks from an existing wall to ascertain this. Tests on the water absorption rates of traditional bricks carried out for Historic Environment Scotland show significant variations:

-

common brick: 7-9% (lower absorption class) and 12.5-14.5% (higher absorption class)

-

handmade brick: 13-17%

-

pressed facing brick: 6-9%

-

extruded brick: 8-9% (lower absorption class) and 11-18% (higher absorption class)

-

glazed brick: 0.5% (fully glazed) and 7-11% (partially glazed).

A brick that has a much higher or lower water absorption rate than the original brickwork into which it is being placed is likely either to cause decay in the surrounding bricks, or to decay itself.

Though it is important not to prioritise aesthetic considerations above technical ones, these also require consideration when matching bricks for repair. The colour of a brick is one of its most significant visual characteristics, and it is therefore desirable to source replacements that match the colour of the originals as closely as possible.

The colour of a brick is due in the most part to the mineral content of the raw material from which it is formed, though aspects of the manufacturing process, such as the temperature reached during firing, will have an impact. Colour can also be given to bricks using a glaze.

Constructions juxtaposing different coloured bricks to create polychromatic decorations can be traced back to the Parthenon in Greece, though the technique was probably used even earlier than that. The short end of wood-fired bricks was purposefully overburnt to create flared headers in Tudor times, while polychromatic buildings were especially popular in the 19th century, with bricks of many different colours used for this effect.

Surface finish is another necessary consideration. As with colour, this is often influenced by methods of manufacturing, with pressed bricks generally presenting a smooth surface finish while colliery shale bricks have a rougher texture. Shape is also significant and has a technical aspect.

Bricks can be shaped during the moulding process, forming what is known as a special, and they can also be cut and rubbed to shape during the construction of gauged brickwork. When matching special-shaped bricks, many brick manufacturers can construct moulds to the appropriate shape (see photo).

Sourcing replacements

The source of replacement for all types discussed in this article is likely to be new bricks. The use of reclaimed bricks, while possible in some instances, can be problematic due to issues with quality and durability, although it is possible to carry out tests on them to ascertain material properties such as water absorption rate and compressive strength.

It may be possible to source bricks that are particularly strong or durable, such as glazed or facing bricks, as reclaimed stock as well. The use of reclaimed bricks certainly has strong environmental credentials, but it is imperative that such bricks are of suitable durability. In most cases, therefore, new bricks will be required. Where a brick type is particularly hard to match, as is the case with colliery shale bricks, as close a replacement as possible – rather than a perfect match – may have to be used.

Moses Jenkins is a senior technical officer at Historic Environment Scotland

Contact Moses: Email

Related competencies include: Construction techniques

Further information

-

Historic England (2015) Practical Building Conservation: Earth, Brick and Terracotta

-

Moses Jenkins (2014) Short Guide: Traditional Scottish Brickwork

-

Moses Jenkins (2018) The Scottish Brick Industry

-

Gerard Lynch (1994) Brickwork History, Technology and Practice (Volumes 1 and 2)

-

Gerard Lynch (2015) The History of Gauged Brickwork: Conservation, Repair and Modern Applications