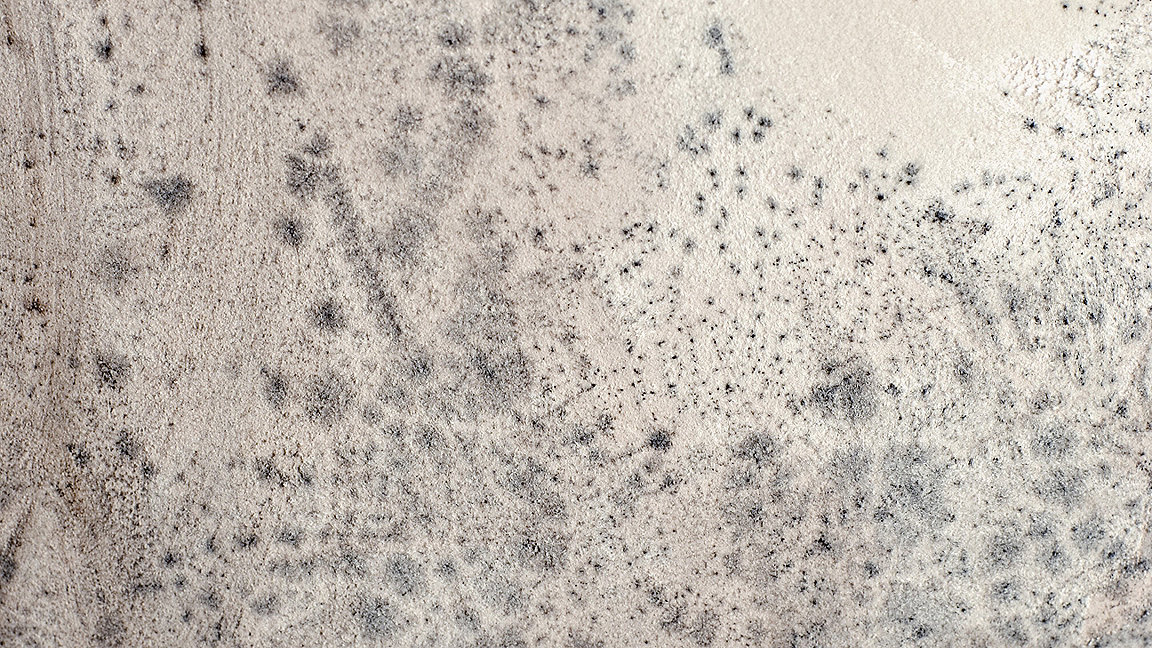

According to BRE data, the NHS spends an estimated £1.4bn annually on treating people for illnesses associated with living in damp and mouldy environments.

Although all buildings are vulnerable, there are a number of variables that – if managed correctly – will significantly reduce susceptibility to damp and mould and the risk of health problems for occupants.

Child death prompts ombudsman report

The tragic death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in 2020, following exposure to widespread mould in the rented Rochdale flat where he lived, has prompted a number of criticisms of typical landlord behaviours relating to mould and damp, and of the legislation that ensures affected tenants have a means of redress.

Among the most prominent of these criticisms was the report Spotlight on damp and mould: It's not lifestyle, published by the Housing Ombudsman in October 2021.

The report attacks what it calls a frequent, knee-jerk reaction from landlords in assigning culpability for damp and mould to residents and their lifestyles. It calls for regulatory and legislative reform to support those living in damp- and mould-ridden environments.

Although there is undeniably some truth to the ombudsman's claims, it is nonetheless equally undeniable that the habits of occupants can have a profound effect on a building's vulnerability to mould and damp.

This means there is certainly a role for residents to play in reducing the risk.

However, a number of factors drastically limit their ability to ensure a healthy internal environment, and landlords need to accommodate these.

Economic factors inhibit tenant action

According to the UK government's English housing survey 2021 to 2022 headline report, 8% of social tenancies and 5% of private tenancies were overcrowded.

But as most overcrowding is unbeknown to landlords – and certainly not advertised by residents – its prevalence in UK rented housing is likely to be significantly higher than this. The risk of overcrowding will undoubtedly increase further if the UK's housing crisis persists.

Although a precise quantity cannot be determined, the number of occupants can have a significant effect on moisture production in buildings.

It is estimated that a family of four alone can produce up to 14 litres of moisture in a single day. Widespread overcrowding will, therefore, significantly increase the frequency of occupants' exposure to mould and damp and the associated health risks.

In turn, one of the primary mechanisms for controlling dampness and subsequent mould growth is heating.

Sustaining a sufficient ambient temperature in a household will reduce the relative humidity – that is, the amount of detectable moisture in the air – and the likelihood of mould growth.

However, the issue for many households is that simply turning on their heating for longer during the day is not affordable.

According to the UK government's report Annual fuel poverty statistics in England, 2022 (2020 data), fuel poverty has been gradually declining since 2010. However, around 13.2% of all UK households were still estimated to be in fuel poverty in 2020.

Furthermore, since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, UK energy costs have increased substantially.

According to the House of Commons' Domestic energy prices report of January 2023, the cost of gas in the UK has soared by an eye-watering 141% since the winter of 2021–22, with rises in electricity costs estimated to be around 65% in the same period.

Despite government intervention to lessen the burden in the form of the energy price guarantee, the war has undoubtedly given rise to further-reaching fuel poverty, meaning tenants throughout the UK are unable to use their heating to combat the health risks associated with prolonged mould exposure.

Another factor is that the number of UK employees working from home increased dramatically in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although recent data illustrates a continued rise in the number travelling back to the office, home working remains popular and is set to continue.

Increased resident occupation during working hours will certainly increase moisture production and consequential mould exposure in homes.

Landlords and regulation targeted by government

A letter issued to social landlords last November by secretary of state for levelling up, housing and communities Michael Gove, shows that the government believes that both regulation and landlords need to go further in protecting the health and well-being of those affected by mould and damp.

In addition, an amendment to the Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023, before it was recently passed to introduce Awaab's law, seeks to mandate strict new time limits for landlords in taking remedial action against reported health hazards, and a national standard for identifying and eradicating mould growth.

My employer, Baily Garner, also worked with the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) as a consultee on implementing Awaab's law, with new damp and mould goverment guidance published in September.

Decent Homes Standard under scrutiny

The Decent Homes Standard has come under close scrutiny since the toddler's death and, according to the English housing survey 2021 to 2022, 3.4m dwellings still failed to meet the standard despite a notable decline in 'non-decent' homes since 2011.

The survey identifies that the highest proportion of non-decent homes are in the private rented sector (PRS).

This supports the conclusion in the June 2022 white paper, A fairer private rented sector, that the legally binding Decent Homes Standard for social housing should be extended to cover the PRS as well.

The charter for social housing residents: social housing white paper, published in December, went on to maintain that the standard does not 'reflect present day concerns'.

This view was shared by coroner Joanne Kearsley in Awaab Ishak: prevention of future deaths report, which identifies five primary concerns, one of which is the standard's failure to consider mould and damp and provide guidance on ventilation in homes.

Meanwhile, the February 2022 policy paper Levelling up the United Kingdom committed to halving the number of non-decent homes by 2030; however, this target is expected to be brought forward following Awaab's death, the sector's focus on mould and damp and the purported failings of the Decent Homes Standard.

'3.4m dwellings still failed to meet the Decent Homes Standard in 2021–22'

Bringing building pathology to bear

One question asked continuously in the immediate aftermath of Awaab's death is how well the built environment professions understand the science behind mould and damp, and the investigations required to arrive at an exact cause and source on an individual property basis.

Gove's letter to social landlords in November has prompted an unparalleled demand for damp and mould surveys.

But both the government and social landlords have overlooked the detail, in terms of the fundamental data they expect these surveys to provide.

Moreover, such surveys have been commissioned on such a scale and to tight deadlines so that they can on the whole only be serviced by basic, non-intrusive assessments.

For the purpose of identifying a landlord's worst-affected properties and taking immediate action to make them safe for occupants, there is value in assessments that use minimal and non-intrusive survey and measurement techniques, and rely principally on visual observations.

However, to fully understand both the issues specific to each property and the long-term remedial intervention required, the holistic approach to defects and remedial action that building pathology brings is fundamental.

Conducting building pathology investigations in the context of mould and damp represents a shift in behaviour from relying on electronic moisture meter-led surveys.

Instead, it requires the use of different tools, techniques and measurements, such as calcium carbide testing and the use of endoscopy.

These can isolate the exact cause of the issue, whether that be the building itself, the occupants or a combination of the two, as well as the most appropriate response.

At Baily Garner, we are currently developing a flow chart to act as a framework for the building pathology approach to mould and damp, detailing the necessary stages and the appropriate action.

Science and standards needed to resolve problem

Although the way residents' behaviour can contribute to damp and mould has been a taboo topic of late, it is clear that the surveying profession needs to increase awareness of the role that lifestyle plays in promoting and maintaining a healthy living environment – and it should not shy away from doing so.

However, landlords need to ensure that they first understand the science behind mould and damp to arrive at an exact cause and source in an individual property, rather than simply blaming tenants without using pathology to identify specific behaviours.

Landlords must consider the external factors that inhibit tenants' ability to combat damp and mould and propose any remedial measures, including innovative provisions such as proactive smart monitoring to identify potential risks long before symptoms are present.

Given the significant number of recent industry publications on the subject, it is equally evident that standards and regulations on mould and damp need to be improved, to better protect the health and well-being of those affected by mould exposure.

Such regulatory and legislative changes will no doubt be well received across the housing sector.

Sonny Cook MRICS is an associate partner at Baily Garner

Contact Sonny: Email

Related competencies include: Building pathology, Construction technology and environmental services, Housing maintenance, repairs and improvement