With the UK’s 2050 net zero deadline and new pressures such as the proliferation of energy-intensive data centres and electric vehicles, bodies including the Public First think tank have warned that the country will face an 'energy crunch point' in 2028 unless more power projects get off the ground.

In response, the UK government has introduced the Planning and Infrastructure Bill. It aims to halve the time it takes to get approval for major projects such as wind farms and power stations.

Ministers have said the bill will focus on making the consultation requirements for nationally significant infrastructure projects more proportionate and streamlined, and they are aiming for 150 such projects to be approved this parliament.

Planning reform necessary but not sufficient

This is a positive development. RICS' parliamentary briefing paper The Future of UK Major Infrastructure Projects rightly described the planning system as 'one of the biggest barriers to major infrastructure projects in the UK … creat[ing] significant delays, costs and uncertainties and [discouraging] investment.'

But building schemes 'as quickly as possible', as the bill intends, will not by itself be enough to ensure the UK secures the resilient, high-performing and reliable energy infrastructure that it needs.

Our focus must be not just on the speed of construction but on many other interrelated factors, including:

- Is the infrastructure designed for the long term, and will it match the needs of users and society in coming decades?

- Will it be as high-performing as intended, without needing constant repair or being out of action?

- Do we have in place the skills and systems to construct, operate and maintain the project effectively?

- Will regulation support the proposed fast-track process?

- Does regulation consider future grid modernisation, the increasing need for economic competitiveness and the high levels of demand expected from mass electric vehicle use, heat pumps and energy-intensive industries?

Without considering these questions the bill's objectives will not be met, and we run the risk of completing programmes at speed that are neither reliable nor adaptable.

Adaption of electricity transmission network

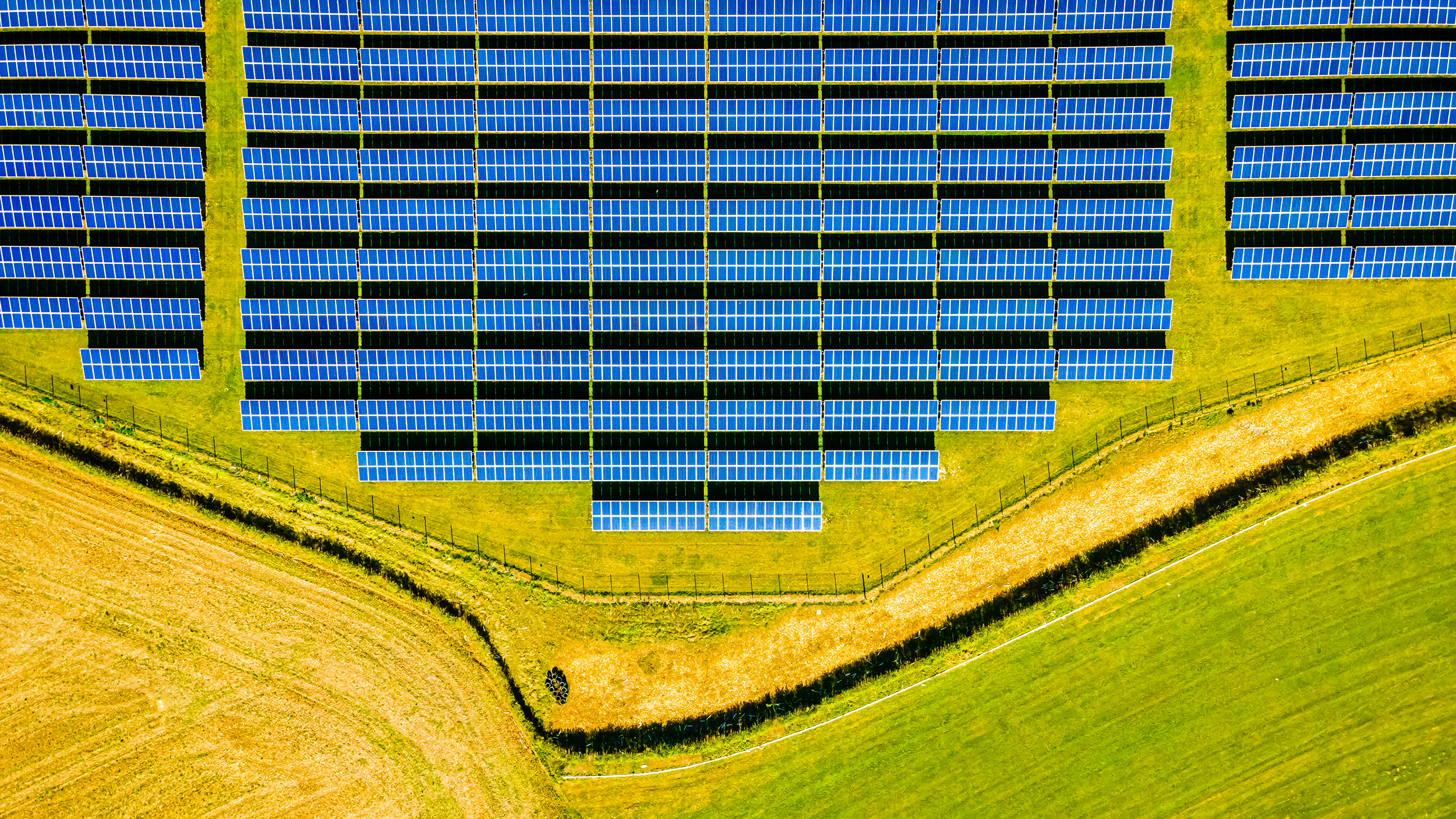

Another important consideration is the adaptation of the electricity transmission network. The Great Grid Upgrade is a National Grid scheme which aims to deliver the required changes and new infrastructure needed to enable the grid to deal with electricity from new sources, such as onshore and offshore wind and solar power.

In his independent 2023 report, which was commissioned by the government, Tim Pick, chair of the Offshore Wind Growth Partnership, warned of the 'urgent need … to upgrade our national grid' and said that grid constraints were becoming a 'significant brake on wider economic activity.'

Linked to this is the need for battery energy storage systems, which, as National Grid has said, are 'essential to speeding up the replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy' by enabling energy from renewables, like solar and wind, to be stored and then released when the power is needed most.

Up-to-date data can support resilience

Before rushing headlong into construction, we must start with a basic principle – that our critical infrastructure is an interdependent system of systems. What happens in one part of the network can have a significant effect elsewhere.

This was underlined by the Heathrow substation fire in March, which resulted in one of the world's busiest airports being closed to all flights and prompted a multitude of questions as to the ease with which such a situation could unfold.

To anticipate events like this – or worse – and react quickly, we need digitalised information management with reliable, trusted data on each major asset, its performance and condition. This should be kept up to date so that vital information is readily available to authorised users throughout the infrastructure's life cycle.

Coupled with this, we should establish digital twins to enable the highest level of operation and maintenance for critical energy assets. These digital replicas are connected to the physical asset, whose condition they report using operation and performance data collected by sensors, the internet of things and cloud-hosted supervisory control and data acquisition.

This may seem counter-intuitive. After all, digital replicas themselves require servers, data storage and constant computation. However, the crucial concept is net energy impact, and the relatively small and increasingly efficient energy footprint of the digital twin's infrastructure is dwarfed by the massive, systemic energy savings it unlocks in the physical world.

As well as enabling us to optimise the performance of the asset, this approach can be used for scenario planning, testing for the impact of potential shocks and stresses and helping to flag issues before they become crises.

Scale of skills shortage remains challenging

Fast-tracking the planning process will require professionals with the right skills for the work. also not resolve the UK's skills shortage.

The 2024–2028 Construction Skills Network report found that more than 250,000 new construction workers will be needed by 2028 to conduct the expected levels of work.

While a Public Accounts Committee report, published in May 2024, warned that the UK lacks the 'necessary skills and capacity to deliver ambitious plans for major infrastructure over the next five years'.

The report added that the government will fail to meet challenges in infrastructure construction 'without a robust market for essential skills in place … as shortages push costs up in a globally competitive environment'.

The skills required for major infrastructure construction, operation and maintenance today go far beyond those needed in the past.

This resource shortage was also a factor in the findings of the Infrastructure and Projects Authority's Annual report 2023–24, which considered 12% of the programmes in the government's portfolio unachievable.

In the energy sector, where programmes can be hugely complex, the necessary supply-chain requirements are typically just as complex. Here too, digital skills can improve efficiency and help teams to do more with less.

To address the built environment skills shortage properly, we need a centralised programme to map out precisely which capabilities are needed over the decades ahead and develop strategies to secure these.

'The skills required for major infrastructure construction, operation and maintenance today go far beyond those needed in the past'

Regulation must enable evolving infrastructure

Regulation for energy infrastructure needs to keep pace too. Currently, even getting meters fitted in a new development can be fraught with problems such as limited space being allocated for them and the associated equipment.

Capacity is another central issue, with the electricity grid not designed for renewable sources and the distributed way they generate energy.

We also need to provide long-term policy certainty to encourage investment in resilient infrastructure and implement regulatory frameworks that can evolve with new technologies.

Only with consideration of all these factors can we ensure our existing energy assets are used fully, remaining resilient and effectively managed, as well as ensuring that new projects perform as intended.

Accelerating UK energy projects is not just desirable, it is strategically essential for the UK’s resilience. But as we transition away from fossil fuels and look to a new era of clean power, let us also shake-up how we deliver and maintain our energy infrastructure and make it data-centred, digital, collaborative and fit for our age.

David Philp FRICS is chief value officer at Bentley Systems Advisory Services

Contact David: Email | LinkedIn

Related competencies include: Construction technology and environmental services, Development/project briefs, Sustainability