In July 2017, the UK reported its first formal dispute involving building information modelling (BIM). In Trant Engineering Limited v Mott MacDonald Ltd [2017] EHWC 2061 (TCC), the claimant applied for an interim injunction until trial or further order, requiring the defendant to provide access to design data the claimant itself had prepared.

The case raised issues about the obligations of the party controlling access to design data prepared by the rest of the team, and the realities of inter-party BIM use.

How the dispute arose

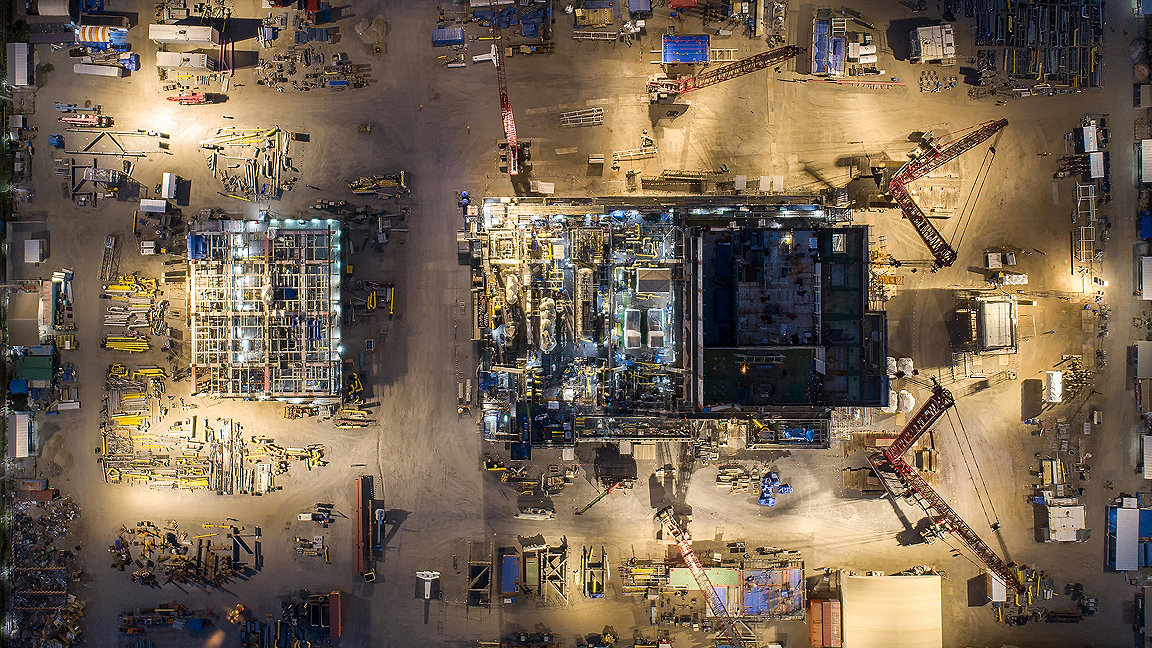

In May 2016, Trant Engineering Limited (TEL) was employed by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to design and construct a £55m power station at the RAF Mount Pleasant complex in the Falkland Islands. TEL then engaged Mott MacDonald Ltd (MML) to provide design consultancy services including, among other duties, implementing BIM.

In doing so, MML intended to use project collaboration software called ProjectWise, which created a common data environment (CDE). MML sent a draft consultancy agreement (DCA) to TEL, incorporating MML's standard terms and conditions. The DCA included a clause on the limitation of liability and provisions for payment, following the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 for interim payments. The agreement also stipulated 'that the contractor … could suspend works in the event of any failure on the part of the client'.

The DCA provision addressing intellectual property rights stated: 'Upon full payment of the fees due under the consultancy agreement[,] the consultant shall grant to the client an irrevocable royalty-free non-exclusive licence to use all rights, titles and interest in any such intellectual property in connection with the construction, completion, maintenance, re-instatement, repair, promotion and/or advertisement[,] whether by the client or by a third party authorised by the client[,] of the project.'

TEL received the DCA contract documents but failed to respond. Subsequently, MML claimed that no contract had been entered into, since its outstanding invoices remained unpaid by TEL. MML then suspended all design efforts, and blocked TEL's access to the design data in the CDE that MML had provided. TEL applied for an interim injunction to force MML to release this data.

Court uses precedent of three-stage test

The court applied the three-stage test in American Cyanamid Co (No 1) v Ethicon Ltd & Ethicon [1975] AC 396 and found that the claim satisfied the criteria, namely:

- whether there was a serious question to be tried

- whether the damages would be adequate, and

- whether there was a balance of convenience.

In terms of the question to be tried, both parties were clearly in dispute regarding the services MML was to provide and their value, and its entitlement for payment; whether a contract existed; whether either TEL and MML were in breach of any such contract, and, if so, what were the implications for any entitlement to retain access to or use any design data.

MML argued that monetary damages would be an adequate remedy for TEL if there were a delay to the project because of the latter's inability to use design data held on ProjectWise; that is, while MML withheld the data, it was willing to compensate TEL for this.

TEL responded that the award of monetary damages would likely be wholly insufficient if the injunction were not granted, as the losses resulting from a year's delay would very probably exceed the DCA's £1m limitation of liability.

TEL cited AB v CD [2014] EWCA Civ 229 where Underhill LJ referred to an earlier case of Bath v Mowlem, which stated that: 'The primary obligation of a party is to perform a contract. The requirement to pay damages in the event of a breach is a secondary obligation […] The rule … that an injunction should not be granted when damages would be an adequate remedy should be applied in a way [that] reflects the substantial justice of the situation.'

The court found that damages would not be an adequate remedy for TEL or MML, since the likely losses on the project would exceed the limit on damages recoverable from MML; conversely, MML would itself suffer a loss of bargaining position. If no contract existed, MML might be entitled to more by way of restitution than if it were providing the services under the contract, with or without additional fee entitlement due to a change in scope. In sum, the court found that the financial damages to the parties in the face of such a delay would be difficult to identify and value.

Regarding the balance of convenience TEL argued that, without restoring its access to the design data, the project could not move forward. The work would effectively then need to be restarted, and a year's progress would be lost. TEL also argued that the court should allow it access to the design data, since MML had already performed the design services that led to the creation of that data and this would allow the project to advance.

The company further contended that there would be very little harm to MML if the court required it to provide access to design data that it had already produced, particularly given that TEL had undertaken or offered to pay for the outstanding fees or damages. The court found that the balance of convenience was with TEL and granted the injunction.

Settlement prompts further dispute

A fresh case, Mott Macdonald Ltd v Trant Engineering Ltd [2021] EWHC 754 (TCC), was heard in March last year involving the same parties.

This arose from a settlement and services agreement the parties entered into in November 2017, with the intention not only of resolving the existing primary dispute but also to govern the parties' future actions. The 2021 case focused on the exclusion and limitation clauses in this agreement that MML had against TEL in the event of breach.

Judge Eyre QC concluded that, when properly construed, the exclusion and limitation clauses in question were applicable to any breach of the settlement and services agreement by the claimant. That meant that MML's liability was limited to the terms of the liability cap in the settlement and services agreement despite TEL's claims that the losses stemming from its breach were considerably more.

How plans of work and information management can help

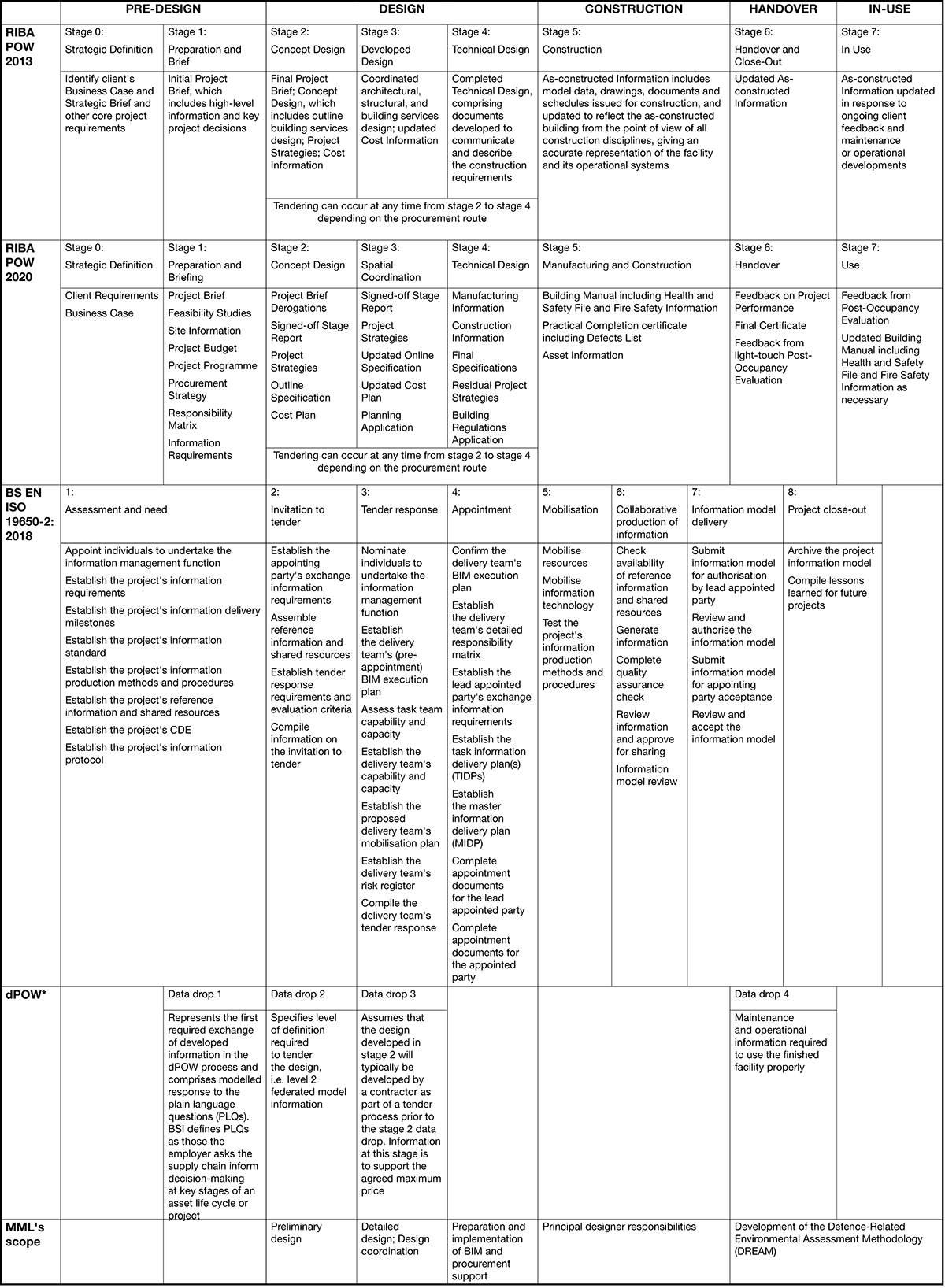

The 2017 case illustrates how project workflow has evolved in recent years. Work stages in different jurisdictions may differ slightly in terminology, but in most instances the general pre-design, design, construction, handover and in-use principles are followed, as per the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Plan of Work 2020.

Table 1: Comparison of MML's scope of services with RIBA Plan of Work, UK government's (NBS) Digital Plan of Work (dPOW)* and BS EN ISO 19650-2: 2018.

(right click image to open full size in a new window)

*Source: based on RIBA Plan of Work 2013 Guide: Information Exchanges by Richard Fairhead

The dispute between TEL and MML was about which of them had ownership of and access to the data in the CDE.

The key to having a collaborative working environment was an agreement about the CDE, which established that MML would develop by using the collaboration software ProjectWise. This may well be part of the BIM Execution Plan, 'a plan that explains how the information management aspects of the appointment will be carried out by the delivery team' as stated in BS EN ISO 19650-2:2018.

Defining the design outputs required for information management at the start of a project is critical. In the dispute between MML and TEL, the court in 2017 did not decide whether a contract did or did not exist. However, it did say it is essential for the parties to agree on the details related to the data required. Since the key outputs are defined by the employer, according to the dPOW, it is critical to know which party has control over this process to have a clear, concise, and definitive conclusion.

In practical terms, the CDE and workflow should be used for managing information during asset management and work on the project. BS EN ISO 19650-1:2018 provides some guidance about asset information models (AIMs) and project information models (PIMs).

AIMs, which relate to the former, that is the operational phase, and PIMs, which concern the latter, that is the construction phase, can be structured or unstructured.

Structured repositories of information that inform decisions throughout the building life cycle include models, schedules and databases, while unstructured repositories include documentation, video and sound recordings. Both could also include existing asset information about the project, and ideally be made available to the lead appointed parties, thus enabling AIMs and PIMs to inform the appointment of parties involved in asset management and construction.

BS EN ISO 19650-1:2018 outlines the principles for information management. It recommends 'information container-based collaborative working', so information can be accessed by those who require it to perform their contractual obligations. This way it avoids issues such as unauthorised access, information loss or corruption, to name a few.

Understanding costs and obligations on design data

The generation of design data comes with a cost. In 2017, the evidence showed that the financial harm to MML from a requirement that TEL be given access to specified data after the first year of design effort was very little.

The court found that it was fair and reasonable for MML to make available the design data it had already produced, and for TEL to pay the sum with respect to the outstanding invoices. Given that the project could not progress unless TEL's access to the data was restored, the court found that it was appropriate to permit access to the design data that MML had already produced at the time that the suspension occurred. In addition, TEL had undertaken to pay the compensation due to MML.

Conversely, if the project proceeded MML would likely continue to incur unremunerated costs for BIM production, without clarity on the issues related to the design data model. As acknowledged in the court's judgment, MML's entitlement to a fee with respect to the design data would be difficult to identify and to value, barring the parties' agreement on governing provisions.

This case therefore provides an important lesson for designers, who should be aware that their primary obligation is to perform their contractual duties; any attempt to recover monetary damages is a secondary priority. As such, designers should ensure the clarity of their contractual obligations, and that the valuation of a breach of contract by the employer provides adequate remedy should they incur such damages.

This valuation could be allowed for when the parties follow the stage 0: Strategic Definition provision of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 and 2020. Such valuations are also affected by the procurement model selected, particularly because the level of information to be provided by the designer at stages 2 and 3 may vary, for instance when there is a two-stage design-and-build contract rather than a traditional construction contract.

Furthermore, if the designer is coordinating and hosting the CDE, this comes with the weighty obligation to ensure that information is shared at the appropriate time with other project members because of the potential monetary repercussions and delays in the programme. These factors need to be considered when agreeing the fee entitlement and payment cycle.

Joan Malana Kennedy is an assistant expert witness in Sense Studio, a part of J.S. Held's Construction Claims & Disputes practice

Contact Joan: Email