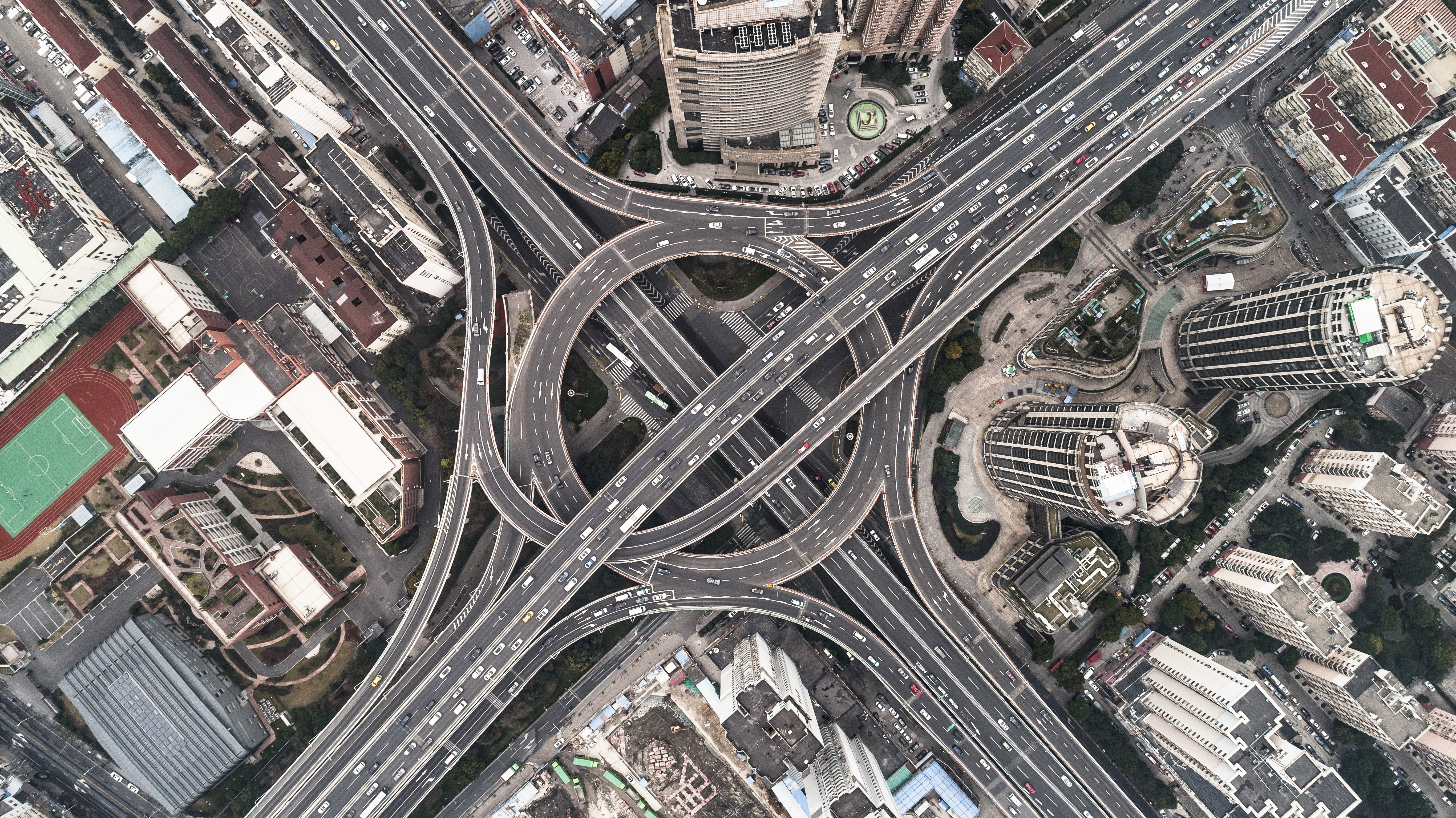

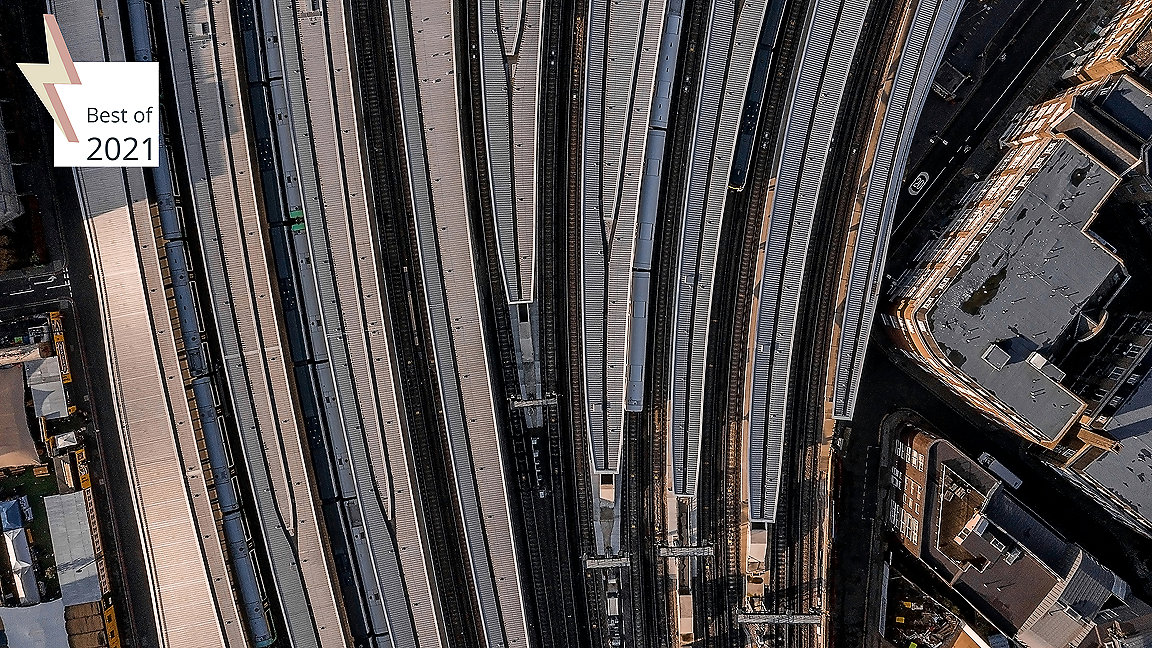

Uncertainty is inevitable on complex infrastructure projects – which makes choosing and drafting contracts a challenge for the lawyers and the project team.

There are many ways to approach this process, but it is often about striking a balance between, on the one hand, a detailed and prescriptive approach that aims to provide certainty, and, on the other, a less detailed, purpose-led approach that provides more flexibility.

While there is necessarily some tension between certainty and flexibility, both can be appropriate. In practice, they can even be combined, depending on the type of project and the parties' commercial aims and priorities for the project.

The traditional approach to drafting contracts is based on creating a document that identifies in full how the risks are allocated between the parties, and what would happen in every eventuality. Such contracts tend to focus on the parties' rights and obligations, trying to identify potential disputes and how they would be determined. The FIDIC 2017 Red Book edition is said to be 150% longer than the equivalent 1999 edition, largely as a result of various additional contractual procedures in order to increase certainty, and in consequence is seen as highly prescriptive.

The opposite approach is based on identifying the purpose of the contract and creating a framework that is flexible enough to deal with any eventualities, based on the parties' overall intentions for the project. This however may mean the contract contains no clear answer as to how certain circumstances are dealt with, unless the parties share a common understanding of the contract's objective and can agree on how to apply its underlying principles to resolve the issue.

In practice, contracts tend to be a combination of both approaches, depending on the specific circumstances underlying the agreement and the likely level of uncertainty. A contract for the purchase of a car, for example, has very little uncertainty and can follow the traditional model; but the more complex and lengthy a project is, the more difficult it is to ensure certainty and provide for all eventualities.

Considerations from the courts

The UK courts generally tend to favour certainty, but it is worth looking at some observations made in a recent decision in Ardmair Bay v Craig [2020] CSIH 21, where Lord Drummond Young made the following observation.

'The most extreme problem with a totally literal approach to construction occurs in cases where supervening events are not readily foreseeable, especially the sort of events that are sometimes described as "unknown unknowns".

'In such cases it cannot be said that "the parties must have been specifically focusing on the issue covered by the provision when agreeing the wording of that provision"; and it is unrealistic to emphasise the parties' control over the language that they use in a contract.'

He also highlighted the risk of a literal approach being used to address all eventualities, observing as follows.

'In cases of that nature, an emphasis on a strictly literal approach may produce a result that is arbitrary or disproportionate, which is plainly undesirable as a matter of commercial common sense.

'Alternatively, a highly literal construction may lead to significantly longer contracts, a practice that is likely to impose greater transaction costs on the parties than occur at present.'

While longer contracts may not see a significant increase in transaction costs, Lord Drummond Young may have also had in mind the costs of disputes arising in relation to such contracts.

He further emphasised the importance of identifying the purpose of the contract, stating that 'the provisions of a contract must be construed purposively, that is, in such a way as to give effect to the fundamental purposes of the contract; points of detail or niceties of wording should not stand in the way of achieving the contract's basic purposes. What the basic purposes are must obviously be determined on an objective basis, and the context is relevant.'

More in this series

Procuring infrastructure collaboratively

Collaboration has clear advantages in procuring complex public projects – so why do traditional approaches prevail? Andrew Dixon explores why the transition is so slow

.jpg)

Balancing certainty and flexibility

A way to balance certainty and flexibility is to put in place a contractual structure that identifies the purpose and provides certainty as to how some matters are dealt with, but still recognises that there are some issues that cannot be fully addressed when the contract is executed. While agreements which rely on a later agreement of key terms – often referred to as agreements to agree – are not generally enforceable, the courts are able to do so in certain circumstances.

In Petromec Inc and others v Petroleo Brasileiro [2005] EWCA Civ 891, the Court of Appeal enforced an obligation to negotiate in good faith because the matter in question could be objectively assessed by a third party.

This was also confirmed in MRI Trading AG v Erdenet Mining Corporation LLC [2013] EWCA Civ 156, which made the point that while the parties had used the term 'to be agreed', the tribunal should have approached the construction of the agreement so as to preserve rather than undo the parties' bargain. This is more likely to reflect what the parties intended when negotiating, as opposed to any views they expressed when a dispute arose.

The issues identified above are not new: for some time legal scholars have been talking about the difficulties that a traditional contractual model has in dealing with complex commercial situations. While recent cases such as Yam Seng Pte Ltd v International Trade Corp Ltd [2013] EWHC 111 and Bates v Post Office Ltd (No. 3) [2019] EWHC 606 (QB) have highlighted the concept of relational contracts, it is not a new argument. It was raised 20 years ago, albeit unsuccessfully, in Baird Textile Holdings Ltd v Marks & Spencer Plc [2001] EWCA Civ 274.

The concept of relational contracting was developed by Ian MacNeill in the late 1970s, to provide the flexibility for complex and long-term contracts that didn't exist under traditional contracts that try to address every eventuality. More recently, in 2003, Arthur McInnis suggested that as the NEC form of contract operated at cross purposes to traditional contract law, it was a relational contract which operated on the basis of cooperation, drawing on the notions of good faith and fairness.

Collaborative contracts

Can the contracts currently available be used in a way that offers the flexibility to deal with the inherent uncertainty of complex construction projects?

NEC4 is a collaborative form of contract that offers scope to include matters requiring further discussion and agreement. This is the case, for example, in relation to accelerating the works under clause 36, or option X21, which concerns how proposals to reduce whole-life costs are managed and their benefits shared.

A more substantive example is the use of option X22 and early contractor involvement. This creates two stages in the contract, on the basis that the first requires agreement on the price and programme, failing which the parties will not progress to the second, which involves the actual construction work.

Alliancing contracts, which require collaboration on the basis of what is best for the project as a whole, can be used to manage unknown risks. In 2017, a new Framework Alliancing Contract (FAC-1) was published by the Association of Consulting Architects. Changes to the scope or nature of this contract require agreement from all members; should a dispute arise, the resolution process starts with a meetings where parties are expected to 'make constructive proposals in seeking to achieve an agreed solution', followed by the option to use conciliation or a dispute board before formal dispute court or arbitration proceedings.

NEC published its Alliance Contract in 2018. Clause 95 of this provides for resolving and avoiding disputes, based on either an independent expert providing an opinion to be used by the board, or reference to senior representatives, who may appoint a mediator to help them.

These collaborative forms of contract are all premised on cooperation between the parties where their interests are aligned. This means that when an unforeseen risk occurs there is a process in place that encourages discussion and resolution by agreement – which need not be limited to the existing terms of the contract.

Drafting for every single eventuality on a construction project will become increasingly challenging, if it was ever possible; but a contract that is set out in loose terms will result in an undesirable level of uncertainty.

Instead, broad, high-level principles should be set out along with specific provisions, including a binding process designed to resolve unexpected events. This approach can be effective – but only when the contract creates a collaborative environment in which parties can see how far their interests are aligned.

'Broad, high-level principles should be set out along with specific provisions, including a binding process designed to resolve unexpected events'

Shy Jackson is a partner at Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner LLP

Contact Shy: Email | LinkedIn

Related competencies include: Contract practice, Procurement and tendering

More in this series

How to make collaborative procurement work

Complex infrastructure projects demand collaboration – so choosing the right procurement option is critical. Andrew Dixon offers some advice on how to do so