?$article-big-img-desktop$&qlt=85,1&op_sharpen=1)

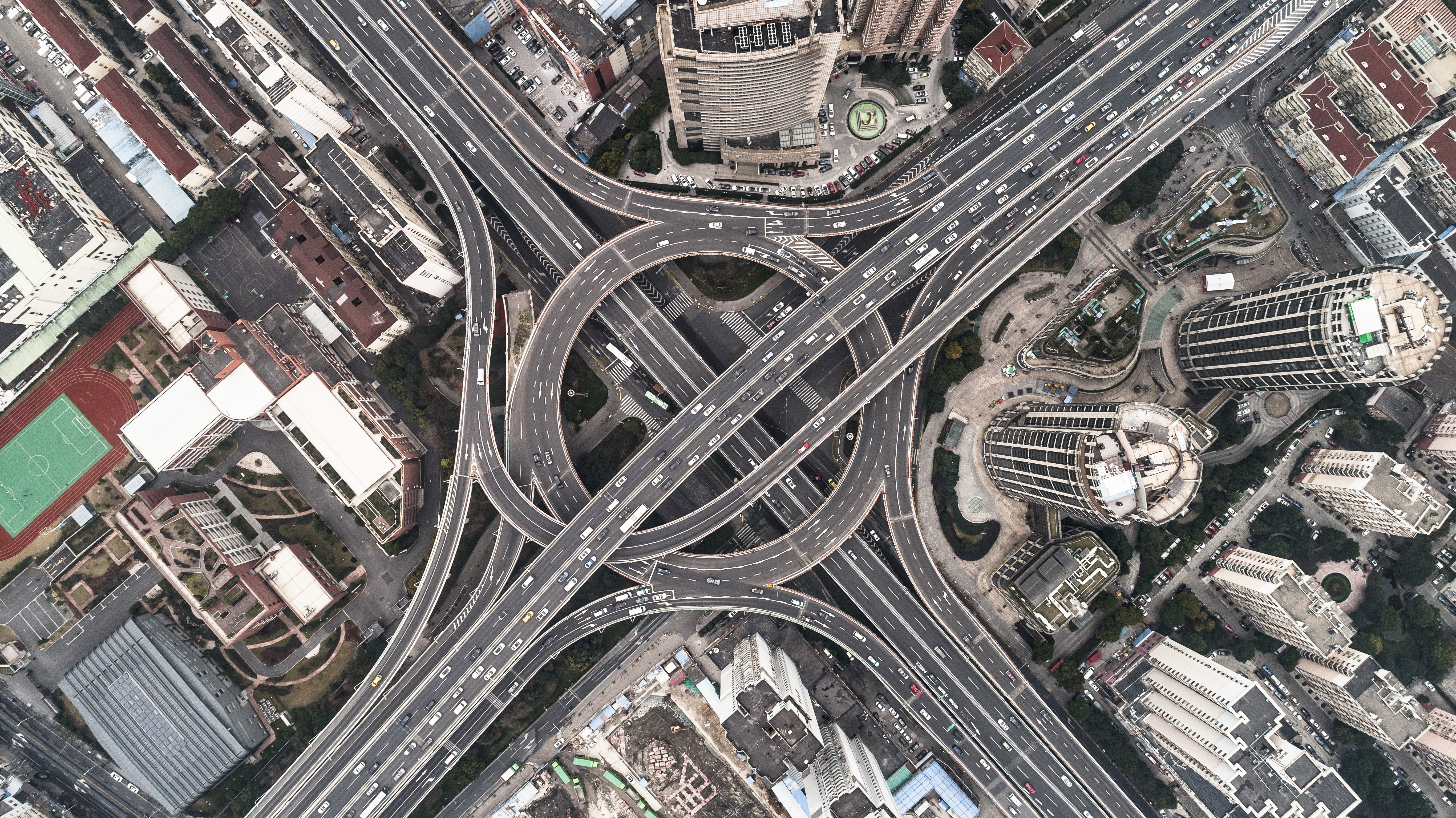

Sydney, Australia. In Australia the public sector frequently procures infrastructure in a collaborative manner

In most countries, the public sector routinely adopts a traditional approach to procure complex infrastructure projects, selecting contractors on the basis of price competition with subsequent contracts allocating them most of the risk.

However, in countries such as Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Hong Kong, Finland, Sweden, the UK, Canada and the US, the public sector is now frequently procuring such infrastructure in ways that optimise collaboration with contractors. All the same, only a few of these countries actually have a policy for collaborative procurement.

Given that complex infrastructure projects procured traditionally often fail to fulfil their cost and time objectives and collaborative approaches are demonstrably ensuring better outcomes, this is a counterintuitive situation.

What is collaborative procurement?

Collaborative procurement involves bidder selection primarily through scoring qualitative factors such as capability, suitability of processes, culture, behaviours and resource quality.

The selection occurs earlier in the project life cycle and, as a result, the commercial scoring assesses the ability to deliver value for money. The subsequent contracts provide for an incentivised fee based on project outcomes and the owner retains most of the risk.

Reluctance and reinvention

Complex public infrastructure is expensive yet vital for national prosperity, so when projects do not meet their objectives the consequences can be severe. Despite these failures, the public sector remains some way from making a transition to collaborative procurement methods.

The explanation for this reluctance appears twofold: structural factors reinforce the status quo, while the public sector is also nervous about what the collaborative approach entails and its own ability to take responsibility for greater risk.

However, there is a shift towards collaboration, both in the construction sector and in global commerce, meaning that the public sector may soon have to overcome its reservations and the structural blockers if it wants to provide complex infrastructure.

The shift is happening for two related reasons. First, project complexity is increasing due to the rise of new technology and delivery partners are reinventing their business models as they develop new skills to deal with this. Second, at the insistence of investors and shareholders, these contractors are starting to push back against the substantial risks they are being asked to bear.

Uncertainty and complexity mean that the success of a project is contingent on the team's ability to make quick decisions in rapidly changing circumstances. As uncertainty prevents contractors from seeing the future clearly, they are less inclined to accept the risks inherent in lump sum contracting or get involved in projects that are not procured in a way that is aligned to success.

"The public sector remains some way from making a transition to collaborative procurement methods"

Contractual constraints

Traditional approaches to procurement also hamper quick decision-making because risk allocation means contractual processes must be followed. These processes are ineffective when there is too much change, and before long it is not clear which of the parties is responsible for what.

When decisions are eventually made they tend to be based on a party's self-interest, because being responsible for risk leads them to think only of themselves. Aligning this self-interest with the desired project outcomes is unrealistic for complex delivery. As it is impossible to draft contracts to allow for all possible contingencies, these complex projects inevitably become dysfunctional because there is no provision for handling the aggregated volume of change or unexpected events.

In this state of confusion, action must rely on something other than the parties’ original contractual intentions. Pragmatism is needed, perhaps in the form of a negotiated settlement and a project reset. Frequently, however, relationships deteriorate as each party blames the other, resulting in a formal dispute.

Challenging the status quo

These complexities demand a new approach – one that allows parties to work together at the earliest possible stage to make effective decisions and develop realistic objectives they can actually meet. Collaborative procurement enables this and provides a framework for managing uncertainty. While this is now more widely recognised, the public sector evidently needs further help to make the transition and take its stakeholders along with it. The first step is to identify and break down the barriers.

Some in the public sector may already wish to collaborate, but their national procurement laws prevent them, mandating price competition or requiring that all risk must be transferred to the contractor. Such laws were designed to ensure transparency, accountability and value for money, but have not been updated to reflect the changing dynamics of complex major projects.

They are not likely to change quickly in countries where anti-corruption measures are necessary and competition is heavily regulated. Austria, France and Germany, for example, still have restrictive laws in place that prevent alliance contracts being used to procure public infrastructure. These nations are, however, taking a keen interest in collaboration and have convened working groups to collect evidence, so we can expect change soon. Australia sets a great example of mature alliance contracting.

Demonstrating value for money at the point of bidder selection and an apparent absence of commercial incentives for innovation and efficiency are often cited as challenges to collaboration. It is true that these are much more difficult to overcome when a collaborative approach is taken, but they can be objectively addressed in ways that add value to the project. The EU Public Procurement Directive's competitive dialogue approach provides a helpful framework for this, offering an objective approach to contractor selection.

A key factor is that price-led competition means the integrated team cannot be formed at the outset of the project, when realistic solutions to the challenges faced would have the greatest impact.

Therefore owners will need a robust answer to the devotees of price-led competition. Such an answer should allow them to articulate the economic benefits of a collaborative approach throughout the project, showing that these benefits clearly outweigh a short-term focus on an initial contract price that is rarely maintained.

Owners will also have to challenge the position of the infrastructure funders and their advisers because they too are wedded to procurement by the traditional approach, where the only answer to uncertainty is a risk premium. This creates the transactional approach where risk is boxed off as the contractor's responsibility.

The continued popularity of private finance initiatives or public–private partnerships – for example, in France, Spain and the US – as a way to provide national infrastructure, despite questionable value for money, perpetuates structures that involve risk-transfer contracts. This ultimately forces the risk along the supply chain, which can lead to suboptimal outcomes when the delivery environment is complex.

One step forward, two steps back

There are some signs that more progressive funders are seeing the potential collaboration can bring. Some public–private partnerships are using target cost contracts, but they tend become lump-sum arrangements at a certain point of overspend. Nonetheless, this represents progress.

National infrastructure banks are also increasing in popularity, and may provide a way of avoiding the inappropriate allocation of risk to contractors by side-stepping the private funders expectations.

The procurement procedures of the World Bank and other multilateral development banks recognise the need for contractor selection to be based on value, but at the same time they create a strong expectation that price competition and risk allocation contracts will be adopted. This places an often unhelpful emphasis on procedure, rather than the long-term value and flexibility that collaborative models can provide.

However, this is likely to continue for some time, with the World Bank recently signing a five-year agreement to adopt the FIDIC suite for its standard bidding documents. These contracts promote appropriate risk sharing, but like traditional procurement models they transfer substantive project risk to the contractor and owners frequently amend these standard forms to protect themselves further.

FIDIC has announced, though, that collaborative contracts will be added to its suite in 2023. Given that it is presently the default suite for international infrastructure, this could hasten the pace of change, and is an important acknowledgment that collaborative contracting is increasingly considered a viable option.

"There are some signs that more progressive funders are seeing the potential collaboration can bring"

More in this series

How to make collaborative procurement work

Complex infrastructure projects demand collaboration – so choosing the right procurement option is critical. Andrew Dixon offers some advice on how to do so

Repurposing the precedents

Aside from these external factors, owners will have their own internal procurement rules, guidance and methods that will be highly resistant to change. Tradition is a powerful force, and more so in some cultures than others. But other nations have been through this difficult process and, given the supportive spirit of the public sector, help would surely be available in making the transition towards collaboration.

Understandably, public-sector clients may view their infrastructure projects as defined by the local and national context, so when looking at the successes of collaboration elsewhere they may have reasonable doubts over its repeatability. Yet the defining context for choosing the procurement method is actually the level of complexity and uncertainty in the project delivery environment. Clear communication and appreciation of this reality is essential for owners to justify the collaborative approach.

A final doubt over collaboration arises from the many reasons for complex projects' failure to meet their objectives, which is as much due to optimism bias, poor governance and ineffective leadership as inappropriate approaches to procurement. All these need to be addressed for projects to succeed.

The few nations where collaborative procurement has been used frequently typically moved towards it progressively. They dipped their toes in the water with target cost contracts; for instance, NEC Option C in the UK, which shared overspend risk between the owner and contractor. These approaches often allowed for early contractor involvement.

These early collaborative approaches provided rich learning for those nations and the contractors to experience joint decision-making around over some shared risks. Yet with today’s level of complexity, these models will not enable sufficient collaboration because they rely on administering change events through contractual processes and cannot provide for all realistic contingencies; for example, a target cost contract with a 50/50 pain/gain model is, in reality, a diluted lump sum model.

Collaborative skills perhaps come more naturally to contractors than other industry groups, but many contractors are still transitioning to more collaborative ways of working. Years of disagreements over lump sum contracts have produced a legacy of non-collaborative behaviours.

Cost and procurement processes that do not provide the required level of transparency for open-book accounting are further barriers to collaborative procurement for contractors. These shortcomings are well-recognised by the big infrastructure contractors, so the gaps are being closed quickly.

"The few nations where collaborative procurement has been used frequently typically moved towards it progressively"

In the grip of tradition

Today, public-sector clients need to make a speedier transition and go further than the collaborative pioneers. But they can at least learn from previous successes and failures.

Clearly, making the transition from a traditional approach that has been used for 150 years to a full-blown collaborative alternative presents a serious challenge. In the UK, the NEC form of contract was introduced in the early 1990s and it is only in the past decade that the industry has become comfortable with its use, though it is now the standard contract for government work.

The traditional approach remains engrained, and owners will need considerable support to change their practices. Most already know the traditional approach will soon be untenable for the complexities of their projects. The change is therefore only a matter of time.

Once the need for this transition has been acknowledged, the key questions are how to put such contractual structures in place, and how they operate in practice to achieve the desired aims. The following two articles in this series will explore just that, looking at some of the mature collaborative models available to owners.

Andrew Dixon FRICS is commercial director at STRABAG

Contact Andrew: Email

Related competencies include: Procurement and tendering

More in this series

Drafting contracts to cope with the unknown

Contracts for complex infrastructure projects in the UK tread a challenging path between prescription and pragmatism. As a result, the industry is moving towards more collaborative arrangements, as Shy Jackson explains