Almost exactly 20 years ago, the UK government introduced land remediation tax relief (LRTR) as part of the Finance Act 2001 with the aim of making brownfield site regeneration more affordable. Two decades on, is the relief still supporting rejuvenation of our towns, cities and former industrial sites?

Under the auspices of HMRC's Tax Law Rewrite Project, LRTR was tightened up and extended to include remediation of long-term derelict land as of April 2009, becoming part 14 of the Corporation Tax Act 2009.

The Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) went on to recommend the abolition of the relief in 2011 as it felt the relief was not working as intended, citing LRTR as 'not considered to influence behaviour' and 'not a cost-effective method of achieving the policy rationale' which was to encourage land remediation of brownfield sites through tax relief for developers Most taxpayers felt they were not assured of getting it but some pushed the boundaries too far in their claims. The OTS cited 2007/08 figures showing that the average claim was some £33,600, and that total annual LRTR claims were £40m.

The government chose not to take up the recommendation, though, and LRTR remains available today. The latest figures available, shown in Table 1, do not show much more take-up, with some 1,600 claimants and £35m total relief, yielding an average claim of around £22,000. This is not surprising as the rules are now more stringent. At the same time, the estimated cost of LRTR to the Exchequer in 2019/20 was £40m.

| Corporation tax non-structural reliefs | ||||||||

| Five-year cost estimates (figures given in £ million) | ||||||||

| Name | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 estimated | 2019-20 estimated | No of claimants | Year | Average claim £ |

| Land remediation tax relief | 30 | 35 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 1,600 | 2018-19 | 21,875 |

Table 1. HMRC LRTR claims actual and estimated 2015-2020

| Corporation tax non-structural reliefs | ||||||||

| Five-year cost estimates (figures given in £ million) | ||||||||

| Name | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 estimated | 2019-20 estimated | No of claimants | Year | Average claim £ |

| Land remediation tax relief | 30 | 35 | 35 | 40 | 40 | 1,600 | 2018-19 | 21,875 |

As property taxation specialists, we at E3 Consulting see a wide range of projects, and believe that most claims are less than £15,000, but there are a small minority in the region of hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of pounds. Furthermore, a recent change in the tax status for non-resident landlords may see claims increase, as since April 2020 they have become eligible to apply for LRTR.

LRTR offers a significant boost to regeneration, but many more claims should be possible, while many developers are not collecting data effectively on their projects. For some, this is because the data collection costs and tax benefits are not aligned; the project teams are reluctant to collect data as they would have to bear the costs, while the tax benefit sits at head office level. Furthermore, they or their advisers either consider it uneconomic to claim, or have little or no awareness – let alone experience – of presenting and negotiating claims with HMRC. Consequently, firms may be paying too much tax.

Time locked

The date of 1 April 1998, which forms condition B under section 1147(3)(b)(i) of the 2009 Act facilitating claims for remediation of long-term dereliction, has remained static since its introduction. This makes it increasingly difficult each year to validate claims that the site qualifies, as demonstrating that land has not been in economic use since that fixed date is effectively having to prove a negative over longer and longer periods.

Accordingly, we believe that for LRTR to remain effective in helping regenerate these challenging long-term derelict sites, it is essential that the operative date be reviewed periodically, perhaps reinstating the 10–11-year period that was put in place in 2009 when dereliction relief was introduced.

LRTR offers either 50% or 150% relief against qualifying land remediation expenditure (QLRE) incurred on brownfield site remediation in the UK, and is offset against corporation tax. The taxpayer cannot be the polluter, neither can it be connected or associated with the polluter in any way. This can be an issue on joint venture projects or leasehold sites where the freeholder may still wish to share the benefits in redeveloping, say, a former manufacturing site.

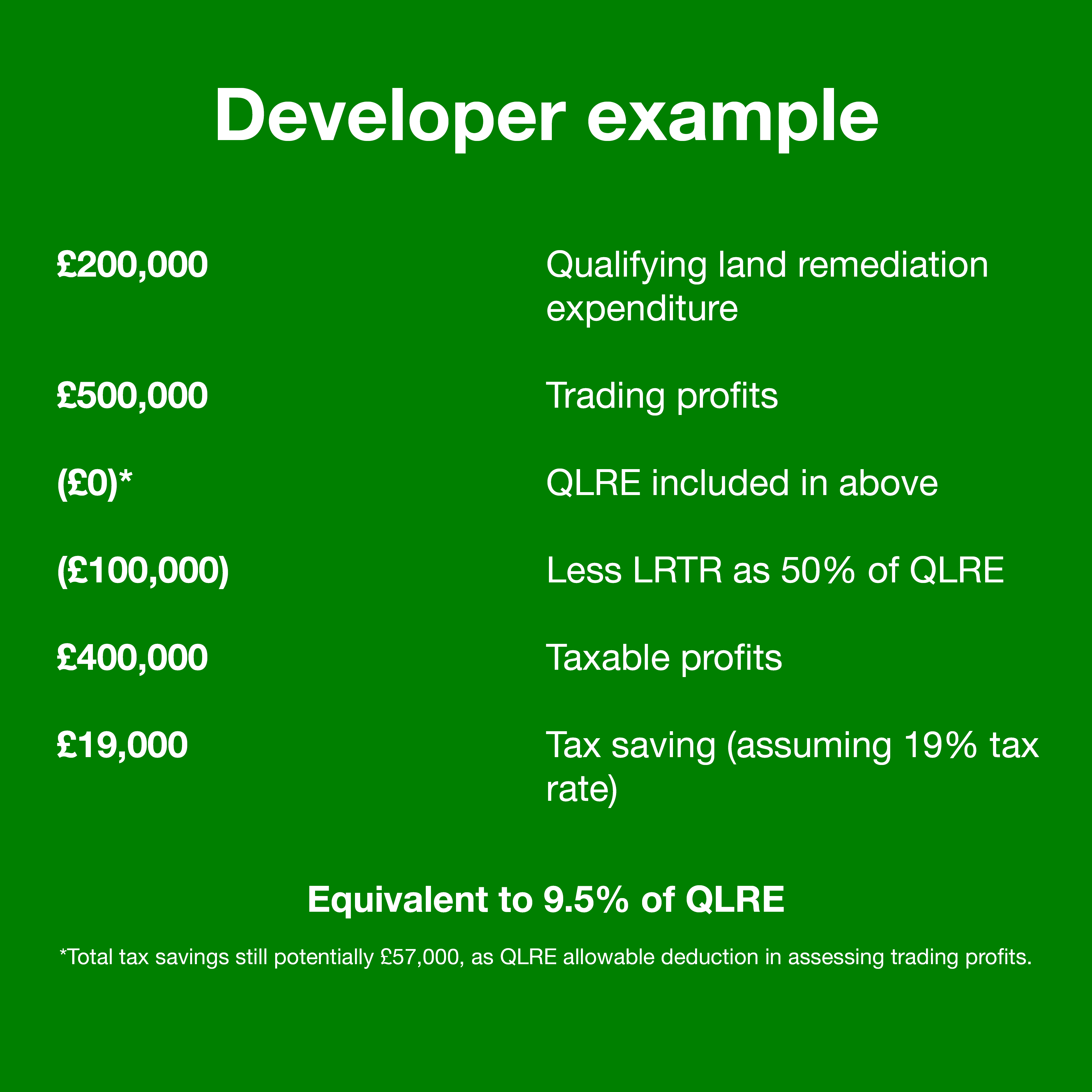

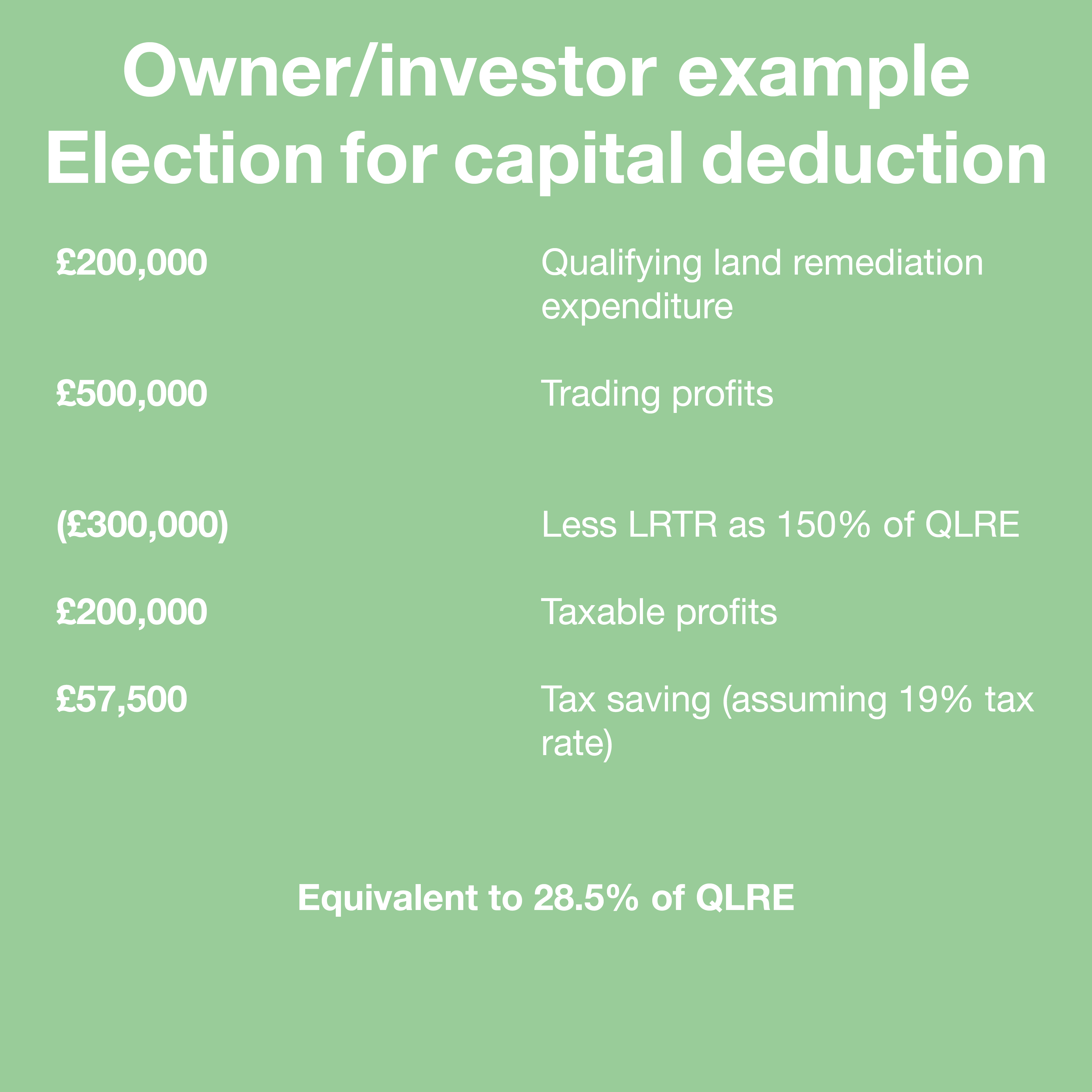

Developers and property traders incurring revenue expenditure are already allowed their base costs as a business expense, and thus LRTR is given at 50% of their QLRE. Investors or owner-occupiers meanwhile get 150% relief as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

The relief is not available to individuals or partnerships subject to income tax, or to charities, pension funds or other non-taxpayers. However, a company that is a member of a partnership can make a claim in respect of its share of land remediation expenditure, provided it satisfies the other relevant criteria.

- should be incurred on land all or part of which is in a contaminated or derelict state

- should not be necessary other than because of the contamination or dereliction

- should be incurred on the relevant remediation of contamination or dereliction

- may include staff and materials or contracted or subcontracted works at arm's-length

- is not otherwise subsidised by grants or third parties

- should not be incurred in the form of landfill tax.

Following the March 2021 budget statement, there will be additional savings available for corporations with taxable profits in excess of £250,000 a year from April 2023, when the main corporation tax rate will increase to 25%.

Tighter definitions

Under section 1178A of the 2009 Act, a taxpayer is required to hold a 'major land interest', defined as a freehold, a heritable title or a leasehold with a minimum term of seven years unexpired, if they are to make a valid claim for LRTR.

This was one of the updates in the 2009 Act, designed to prevent the practice of polluters granting short leases to a third party that would then decontaminate the site and claim the tax relief before the lease reverted back to the polluter's interest.

The established approach to environmental risk assessment means that land can only be considered contaminated if a potentially harmful pollutant, recipient and plausible link between the two can be identified; this is usually referred to as the contaminant–pathway–receptor principle.

While the wording of the 2001 Act meant that a wide array of substances qualified as pollutants, the tightened 2009 rules restricted the claiming of LRTR predominantly to sites contaminated by previous industrial activity. The legislators also took the opportunity to align the tax and the environmental legislation, tightening the wording and clarifying the intention of the law, curtailing the possibilities of companies pushing the boundaries of the rules. The better-established language used in the 2009 rules called for more proof than the earlier drafted tax rules making it more difficult to get the tax relief. It also ensured project criteria were consistent with more mainstream environmental laws such as the definitions of 'relevant harm', and the 'serious possibility' of it occurring.

Too many taxpayers also overlook the potential to claim relief for remediation of existing buildings when carrying out processes such as asbestos removal, thinking LRTR only applies to land. However, the 2009 Act deems land to be contaminated where a pollutant is in, on or under that land. Such substances include hydrocarbons, metals and metalloids, asbestos and a limited number of naturally occurring contaminants such as radon, arsenic, arsenic compounds and Japanese knotweed.

- significant injury, damage or death to living organisms

- significant pollution of controlled waters

- a significant adverse impact on the ecosystem

- structural or other significant damage to buildings or other structures, or interference with them that significantly compromises their use.

To be eligible for LRTR, derelict land must not have been in, productive use since 1 April 1998, and cannot be put into productive use without removing buildings or other structures. The biggest issue here is that land rarely sits idle for so long: we regularly see sites that are awaiting planning permission or development finance used for car boot sales or parking, for instance – breaching section 1145A(a) of the 2009 Act and thus denying the developer any tax relief.

- heavyweight post-tensioned concrete

- building foundations and machinery bases

- reinforced concrete pile caps and basements

- redundant services such as electricity, gas, water and telecoms below the ground.

- containment

- removal

- treatment.

Most suited to limited areas of contamination or areas where removal may be difficult or unduly expensive, containment is the act of encasing the pollutants in situ, closing off all pathways to any receptors. The nature of the future use, as well as the contaminants, will dictate the form of the barrier; examples include bentonite clay, capping layers of concrete or sand, or impermeable geotextiles or membranes.

Containment reduces the need for removal and disposal, mitigating landfill tax costs; but ultimately the contaminants remain on site and so may require further attention in future. However, it may now be possible – or required – to purchase insurance to cover any future remediation requirements.

Where contamination is to be removed and the extent of pollution is determined, the relevant area – not necessarily an entire site – could be excavated by a depth of around 1–3m. The soil is then tested to assess the full extent of contamination, and the polluted material is removed to a licensed tip, backfilled with non-contaminated soil to the necessary ground levels.

Developers used to love this so-called dig and dump method because it was quick and absolute, removing the pollution from the site for good. However, because of regular increases in landfill tax – to £96.70 per tonne for standard active waste and £3.10 per tonne for non-hazardous qualifying materials as of 1 April 2021 – there has been a shift towards more on-site treatment, or a combination of part removal after treatment.

Possible treatment approaches will depend on the contaminants present, other risk factors such as nearby watercourses, and the intended future use for the site. At the same time, science continues to make advances in bioremediation and other techniques.

- air sparging or stripping

- aerobic or anaerobic bioremediation

- chemical treatment for Japanese knotweed

- dual-phase high-vacuum extraction

- enhanced aerobic biodegradation

- filtration, flocculation or settlement

- mycoremediation

- phytoremediation

- rhizofiltration

- soil vapour extraction

- vacuum stripper systems

- vapour- or water-activated carbon.

For example, one former colliery site used bioremediation to promote rapid growth of natural micro-organisms that digested the hydrocarbon contamination, creating the safer by-products of water and carbon dioxide. A network of pipes injecting oxygen was laid in the spoil heaps to accelerate a natural process that would otherwise have taken many years.

Whatever the method of remediation, all tend to be expensive, and potentially challenge the economic viability of any given regeneration site. LRTR helps to mitigate these project risks, accelerating redevelopment of such brownfield sites. In turn, this can nurture an area's economic renaissance and foster new employment opportunities.

Scrutiny and care

Unsurprisingly, with up to 150% relief available, HMRC is vigilant about taxpayers attempting to make invalid LRTR claims. We regularly see challenges on preliminaries and professional fees, which need to be over and above the normal project works and specifically associated with the requisite remediation activities if they are to qualify.

However, most issues arise as a result of poorly prepared claims. For instance, ineligible costs are often included because of the naivety or possibly the laziness of the taxpayer, or occasionally its advisers, in not seeking more detailed breakdowns of lump-sum project costs that involve a mixture of qualifying and non-qualifying expenditure. Careful, thorough and timely analysis of the relevant project costs typically optimises tax savings and enhances cash flows.

Furthermore, under UK tax legislation HMRC can seek to impose significant penalties and interest if it considers a claim is abusive or deliberately misleading. Hence, it is more important than ever that clients and their tax advisers can demonstrate reasonable care in preparing all aspects of their tax computations to counter any challenges. Failure to do so could lead to claims against an adviser's professional negligence insurance to recover overpaid tax, interest or penalties, depending on the circumstances.

It is well worth taking the time and trouble to prepare a comprehensive and watertight LRTR claim for the money it will save your business, and the longer-term benefits for the community in which the site is located.

Alun Oliver FRICS is managing director of E3 Consulting and an accredited mediator

Contact Alun: Email | Twitter

Related competencies include: Accounting principles, Contaminated land, Planning and development, Capital taxation, Environmental analysis, Management and regeneration of built environment, Waste management