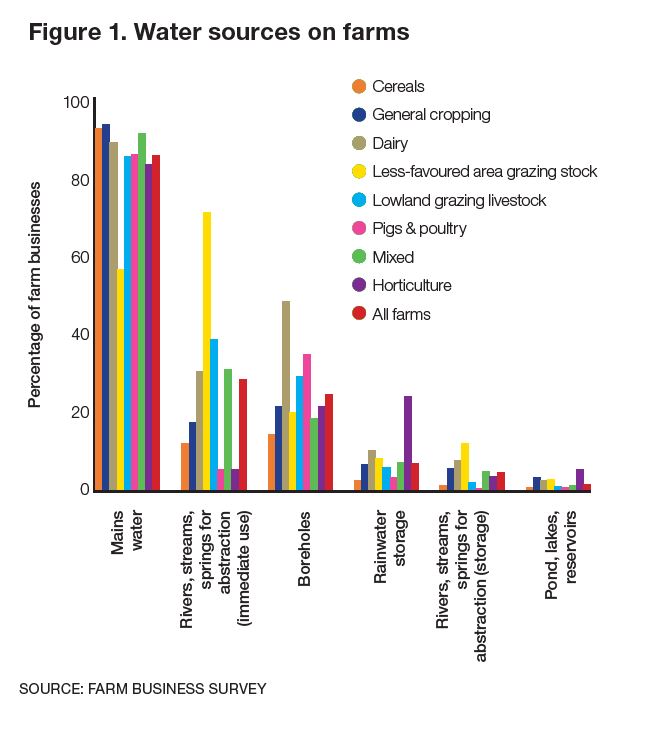

With hot summers like 2018 now more likely than in the last decade, demand for water in UK agriculture and horticulture could be set to rise. While the Farm Business Survey indicates that most UK farms have a mains water supply, depending on the type and location of farm other sources are also used as detailed in Figure 1.

Less mains water is used in the uplands, being more remote, so farmers rely on rivers and streams. Dairy farms use boreholes, as do those rearing pigs or poultry and horticultural businesses growing fruit, vegetables and ornamental plants. Rainwater storage is used in protected horticulture, for instance in glasshouses, mostly because they are in areas of low rainfall. Wherever used, mains water is the most expensive and highest quality due to drinking water standards – a key consideration for horticultural and dairy businesses, where potable water may need to be used to protect consumers.

"Agriculture uses less than one per cent of abstracted water in England"

Livestock accounts for around half of agricultural water demand nationally, including drinking water as well as operations such as cleaning. The 2018 drought was therefore challenging for livestock farming in areas that had been previously unaffected by shortages, because streams ran dry and there was a lack of other water sources. Such farms are also vulnerable to supply disruptions in the winter when frozen or burst pipes can regularly cause problems, posing a potential welfare issue.

In crop farming, water is primarily used for potatoes and horticulture. There is a large trade deficit in horticultural produce, and the UK relies particularly on imports of fruit. However, the country is almost self-reliant in potatoes, and exports around 100,000t of seed potatoes to countries such as China and Egypt, which value the crop for its quality and low disease risk. Would it be possible to increase production reduce trade deficits and increase exports? If so, what limitations would water place?

Agriculture uses less than one per cent of abstracted water in England, which seems an insignificant amount. However, water used on farms isn't returned to the catchment, and in some areas, agricultural abstraction of surface water can have a significant impact on river flow during the summer months. There are currently around 10,000 licences for spray irrigation, representing about 90 million cubic metres used annually, with variation for weather fluctuations.

Around half the UK potato crop is irrigated according to the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), around 10,000ha less than the 2005 baseline. While growing without irrigation is possible, depending on location and market, there could be pressure on production in some years. If rainfall is lower than average this could affect crop quality and yield. Irrigation in the early season reduces the risk of the potato defect common scab.

The rain gun is still the most commonly used technique for applying water in field vegetable and potato growing in the UK. Other techniques such as sprinkler, boom and drip irrigation could improve the efficiency of water use, and these can be integrated with scheduling and monitoring software to help inform decisions on irrigation. The AHDB is working to demonstrate differences in water use and marketable yield when using different techniques and hopes to do more in future to help farmers share their learning about irrigation and water management techniques.

Water abstraction

The Environment Agency (EA) has assessed the availability of water for abstraction, and important fruit- and vegetable-growing areas are shown to have little opportunity for more abstraction licences. Future water availability and ensuring that food can still be produced in these areas will be of increasing importance.

Climate projections published by the Met Office in 2018 indicate that hot summers are expected to be more common and, if combined with lower summer rainfall, crop water needs would have to be met through increased irrigation – but there may be no more water available to licence. The threat to UK production is increasing, and the Met Office suggests that the likelihood of hot summers such as that of 2018 is now ten to 20 per cent when it had been less than ten per cent.

Farmers and growers are certainly aware of this long-term threat to their businesses and trying to manage the situation. In particular, farmers are worried about the loss of headroom in licences during the renewals process, being the extra amount of water allowed for production in dry years, which may not always be needed.

The EA is concerned that if full licensed volumes were used during times of drought when farming needs are greatest, this could be to the detriment of river ecology. Headroom on licences may therefore be reduced to manage the risk to the environment, but thereby increasing risk in agriculture. Cranfield University has developed a tool called D-risk to help farmers evaluate their licences against the potential for an irrigation deficit and to check existing headroom; there is also a tool to investigate the costs and benefits of creating a reservoir.

Licence to grow

Agricultural abstraction licences do not guarantee supply either – for instance, in the event of restrictions. Hands-off Flow restrictions are used throughout the season to stop abstraction when river flow levels drop. Restrictions on spray irrigation under section 57 of the Water Resources Act 1991 can also be used during the growing season to limit access to licensed water at times when the environment could be affected by low river flows, and are a problem for growers who abstract from surface waters. Back-up supplies from groundwater or reservoirs are among the measures businesses can take to improve resilience.

Reservoirs and rainwater harvesting are increasingly common in the horticultural sector, and have greatly improved the water security of businesses. By storing water in a winter-filled irrigation reservoir farmers are able to avoid restrictions on irrigation during summer, and it also means agricultural impact on summer river flows is reduced. These measures help farmers get through dry years; however, they are expensive, costing tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds, with limited financial support available and various planning, technical and management requirements.

The AHDB WeatherHub takes weather data and integrates it with pest and disease forecasting alerts to enable farmers to make management decisions. The board is also looking at ways of integrating this with other open data sets such as drought forecasting to help farmers anticipate unexpected events such as the 2018 drought and the Beast from the East.

While there are opportunities to increase UK-grown fruit and vegetable production, this needs a secure water supply. There are big challenges, not least our weather and pressure from all sectors on limited water sources. The strategies discussed above can help farmers make best use of the available water, supported by effective policy and uptake of technical innovations.

Dr Nicola Dunn is a resource management scientist at the AHDB nicola.dunn@ahdb.org.uk

Related competencies include: Agriculture, Management of the natural environment and landscape

The AHDB is funded through a statutory levy on farmers growers and others and provides resources and guidance for the sector.